The Department of Consumer and Worker Protection (DCWP) took over as the main city agency handling street vendor enforcement last June. But the NYPD remains active in enforcement, too. Together, the agencies issued 2,427 tickets to vendors during the year ending in May, a 33 percent increase compared to 2019, when police alone issued 1,609 tickets.

Daniel Parra

Seated, on the left, the vendor reads the ticket he has just received. On the right, two DCWP agents on Junction Boulevard on July 1.It doesn’t take much for the street vendors on Junction Boulevard and Roosevelt Avenue, Queens, to spot a Department of Consumer and Worker Protection (DCWP) agent—who will soon start handing out tickets.

Though the agents are dressed in civilian clothes, they’re identifiable among the crowds of pedestrians for their nonchalant-but-observant demeanor and the electronic tables they carry, vendors says.

On July 1, several vendors in the area were ticketed: a fruit and vegetable seller because she was using more space than allowed; another because her license was expired; a veteran who sells hats and toys because he was not within the required 20 feet away from a nearby store entrance.

There were other vendors who, upon recognizing the agents, did not unpack their wares for fear of receiving a fine.

City Limits has collected data for inspections, complaints and tickets handled by DCWP—formerly the Department of Consumer Affairs (DCA)—from June 1, 2021, to May 31, 2022, nearly the first full year since the agency took over the main task of vendor enforcement from the NYPD (the switch was officially made in January 2021, but DCWP only actively began issuing tickets in June of last year, having spent the first several months conducting outreach and education instead).

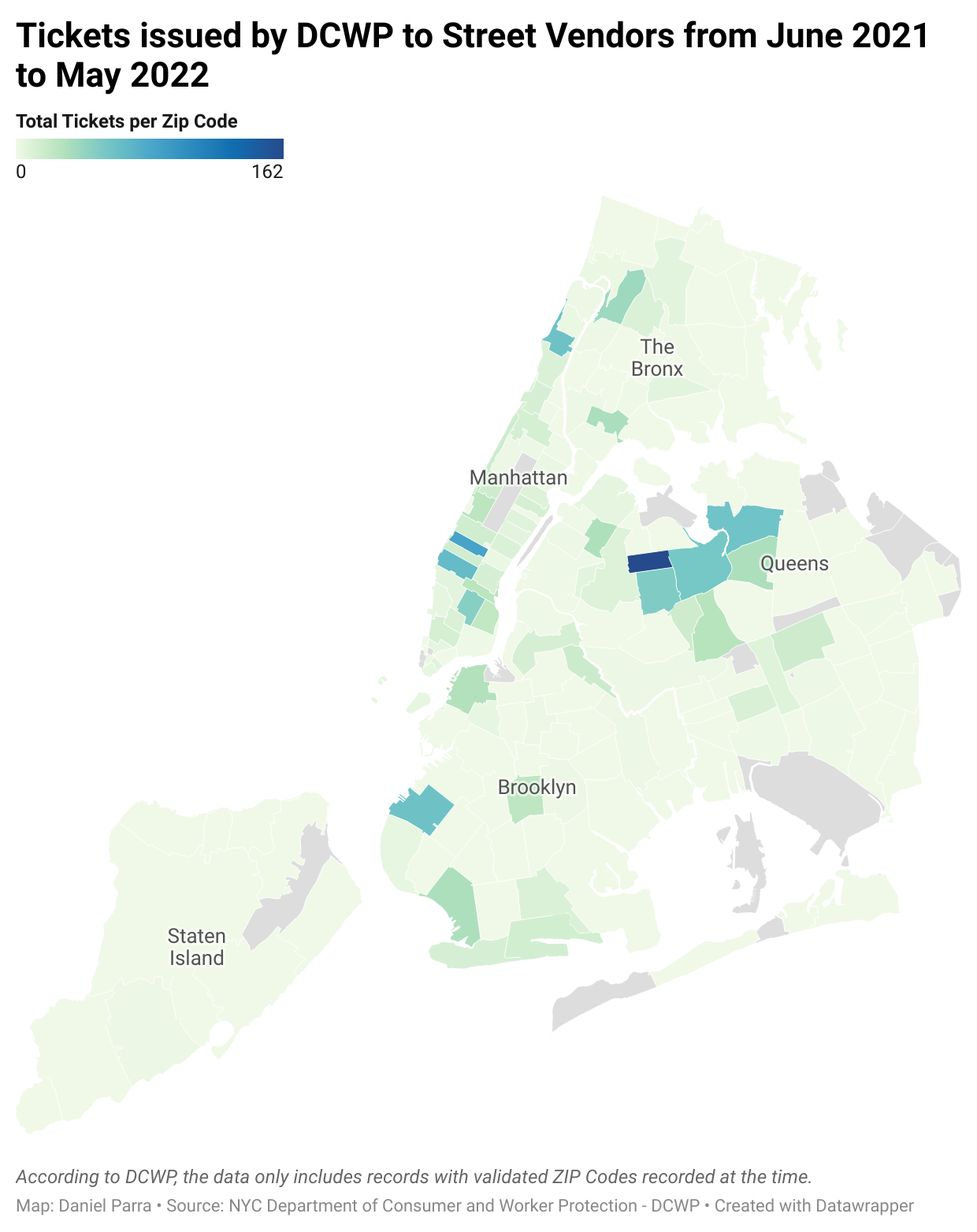

During the first year, DCWP issued almost as many tickets to vendors as numbers reported by the NYPD in the year before the pandemic: 1,463 tickets versus 1,609 in 2019.

But police remain involved in vendor enforcement too, despite former Mayor Bill de Blasio’s pledge to take them out of the process in response to years of complaints by the predominantly immigrant vendor workforce, who said they felt harassed and targeted by officers.

Together, the two city agencies issued 2,427 fines to vendors during this most recent 12-month period, a 33 percent increase compared to 2019, when police alone issued 1,609 tickets. These recent figures don’t include the latest police summons numbers for the second quarter of 2022, so the total will be even higher. In July 2021, the number of enforcement staff at DCWP was eight; by October it had grown to 24, remaining the same since.

“The point of moving street vendor enforcement out of the NYPD was to reduce ticketing violations,” said Council Member Shahana Hanif, chair of the immigration committee. “Sadly, we are seeing the opposite play out.”

Jackson Heights was the most ticketed zip code for vendors under the first year of DCWP enforcement, totaling 162 tickets (76 in 2021 and 86 in 2022).

On that first Friday afternoon of July on Roosevelt Avenue, DCWP officers didn’t approach every single vendor lining the street. Instead, they approached one here and there, including a veteran selling baseball caps, wallets, and small teddy bears.

He later received a ticket for not being 20 feet from the front entrance of a store on Junction Avenue, as required by city rules. Agents on the ground, who used a measuring tape to check the vendor’s compliance, didn’t comment when a City Limits’ reporter on the scene asked about the agency’s inspection process.

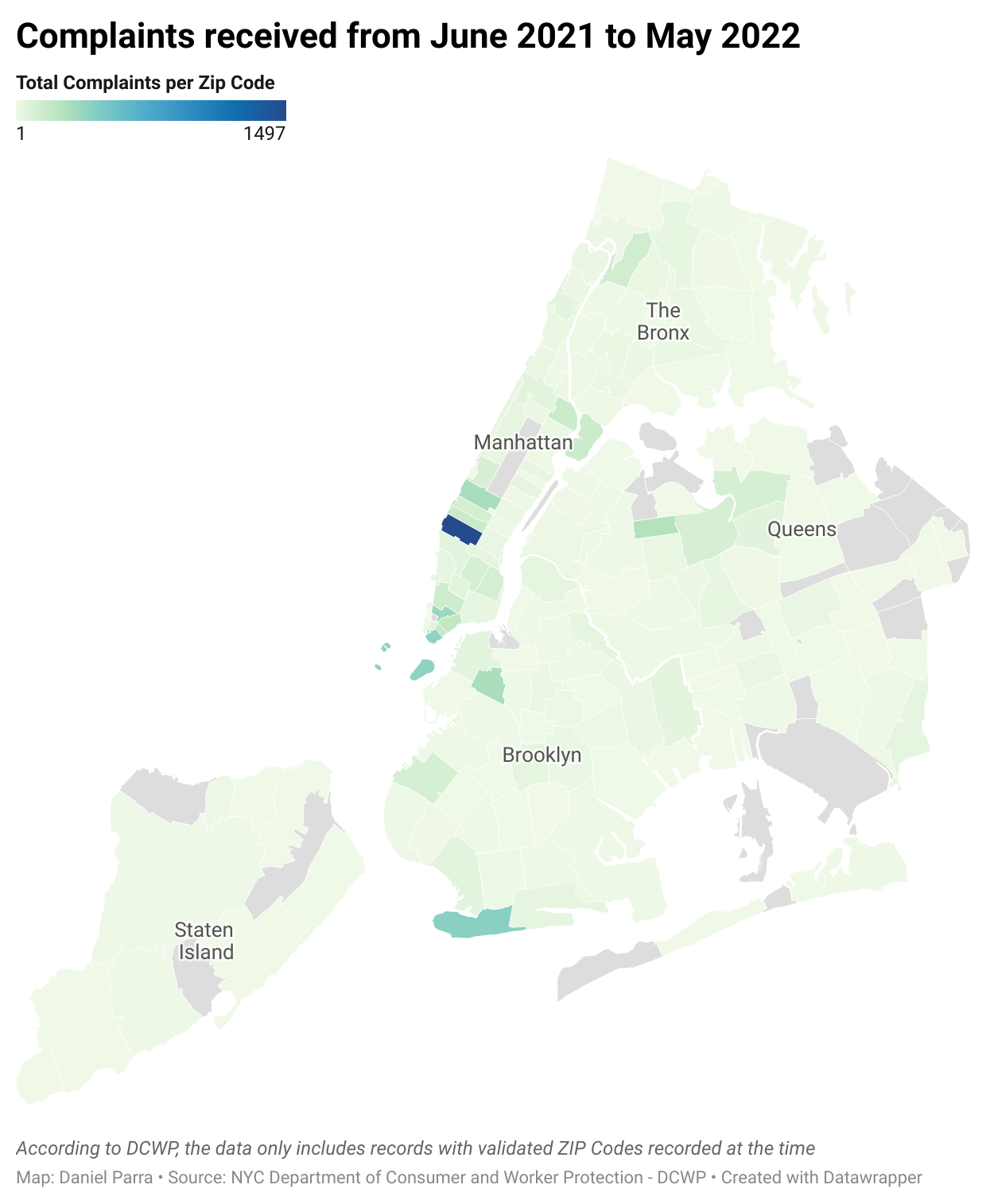

Where the complaints are

In the past, DCWP has argued that enforcement is often a response to complaints—from the general public, elected officials, community boards, and Business Improvement Districts (BIDs), which have historically viewed vendors as competition to brick-and-mortar businesses.

However, neighborhoods with the most complaints do not match neatly to those with the most tickets and in some cases, the most inspections. Chelsea, for example, was the center of vending complaints received by the city, with a high of 1,497 during the 12-month period City Limits examined, but vendors there received only 65 tickets during that time. Coney Island, likewise, had the second highest number of complaints in the same time period, but only saw 12 tickets.

In contrast, the DCWP received 257 complaints about vendors in Jackson Heights—less than one-fifth of the number it received about vendors in Chelsea—but doled out 162 tickets there during the first full year of enforcement, positioning the majority-immigrant Queens neighborhood as the most ticketed in this period.

“Summonses,” DCWP spokesperson Abby Lootens said in an email, “are issued when vendors refuse to correct violations and are more commonly issued in areas where vendors repeatedly ignore DCWP inspector instructions.”

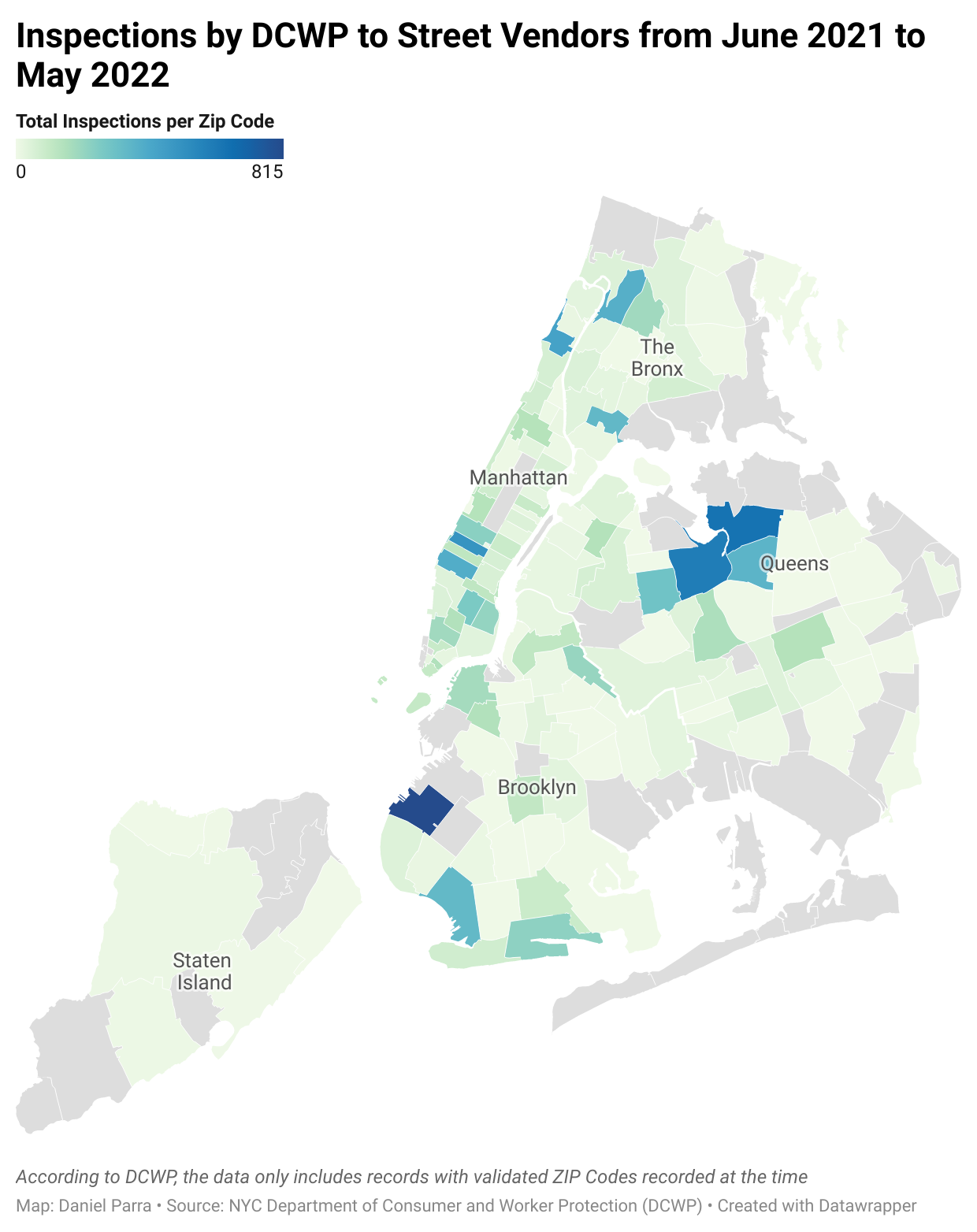

But a similar mismatch between where complaints were received and where inspections took place is unfolding in 2022, data shows. With the exception of Chelsea, which is among the top five neighborhoods for both vendor complaints and inspections so far this year, the other zip codes that garnered the most complaints from the public were not the most inspected. Areas most frequently hit by DCWP inspectors during the first five months of the year include immigrant-rich neighborhoods like Sunset Park, Elmhurst and Corona.

| DCWP Totals For 2022 So Far (as of May 31) | |||

| Borough | Total Complaints | Total Inspections | Total Tickets |

| Manhattan | 2,362 | 1,787 | 285 |

| Bronx | 200 | 573 | 52 |

| Brooklyn | 376 | 1,377 | 103 |

| Queens | 351 | 2,192 | 259 |

| Staten Island | 14 | 9 | 2 |

| Unknown/Out of NYC | 62 | 2 | 1 |

| Totals | 3,365 | 5,940 | 702 |

Queens saw a whopping 2,192 inspections so far this year—crowning it as the most inspected borough—but accounted for only 351 vending complaints, compared to 2,362 complaints lodged about Manhattan vendors.

“Yet again, we are seeing another report of increased ticketing of working-class immigrants who are simply trying to provide for their families,” Councilmember Hanif said. “It is clear the small procedural changes passed on the City level have not worked to end the racist harassment street vendors continually face at the hands of City bureaucracy.”

A DCWP spokesperson insisted that inspection locations are identified in response to complaints.

| ZIP Code | Complaints | Neighborhood |

| 10001 | 886 | Chelsea |

| 10004 | 254 | Southern tip of Manhattan and Governors Island |

| 10007 | 241 | Tribeca |

| 10005 | 146 | Wall Street |

| 10038 | 130 | City Hall |

| ZIP Code | Inspections | Neighborhood |

| 11372 | 86 | Jackson Heights |

| 10001 | 48 | Chelsea |

| 11220 | 36 | Sunset Park |

| 11373 | 36 | Elmhurst |

| 10003 | 34 | East Village |

“Repeat inspections are conducted on streets and in areas with large number of vendors and/or repeated non-compliance,” Lootens said. Indeed, some neighborhoods have seen an uptick in the number of vendors operating there since the pandemic began. Corona Plaza, for example, has seen an influx of new sellers, The City reported this week.

“These numbers validate what we see every day on the streets,” said Carina Kaufman-Gutierrez, deputy director of the Street Vendor Project. During the peak of the pandemic, vendors were celebrated as essential workers, but now they are penalized, she argued.

According to the Jackson Height veteran, the ticket he received earlier this month was his first after a couple of years of working at the same spot on Junction Boulevard.

“I thought it would be a warning,” said the vendor, who didn’t want to be identified by name.

After measuring the distance from the front store to the street vendor’s table, inspectors handed him a ticket.

According to DCWP, joint inspections with the NYPD vary from week to week. This year, police have been involved in approximately 15 percent of vendor inspections, the agency said.

Not the change they hoped for

Advocates and vendors, many of whom are immigrants or people of color, thought the days of overly-punitive enforcement might be over when former Mayor Bill de Blasio put DCWP in charge of oversight functions previously performed by the NYPD alone.

Vendors and those who advocate for them say the continued pace of ticketing has made it harder for those who work in the sector to recover from the effects of the COVID-19 crisis.

“Senate District 13, which overlaps with many of the zip codes with high rates of NYPD activity related to street vending enforcement, was also the national epicenter of the pandemic,” said Senator Jessica Ramos’ Communications Director, Astrid Aune.

“Many of our constituents were ineligible for pandemic relief because of their immigration status or work classification, and they took to the honest work of street vending because they needed a way to pay bills. They are not the first to do this, nor will they be the last—street vending is as old as New York,” she explained.

Both Hanif and senator Ramos’ office insisted on the importance of removing the cap on street vending permits in New York, which for decades has made it extremely difficult for vendors to operate legally, since demand greatly exceeds the small number of available permits, which can sell for tens of thousands of dollars on the black market.

The City Council voted last year to reform the system by issuing an additional 400 permits each year for a decade, increases that were supposed to happen this summer, but have hit delays.

But advocates and some lawmakers say that change wouldn’t be enough to truly overhaul how street vending operates in New York, prompting Ramos to sponsor a bill this year that would have eliminated the permit cap altogether.

“The data surrounding tickets, summons, and general enforcement lays out precisely why our office has attempted to legislate a path to formalization for street vendors,” said Aune.

But Ramos’ bill did not pass in the most recent legislative session, pushing the issue to lawmakers in 2023, unless the City Council takes it up again.

“It’s far past time we pass Senator Ramos’s bill to end the archaic cap on vending licenses and bring thousands of hard-working New Yorkers out of this shadow economy,” Hanif added.

12 thoughts on “Street Vending Tickets Went Up During First Year of New Enforcement Policy ”

Another factually distorted article on vending. The reason there are more vending complaints in Chelsea and other areas but far fewer summonses is not racism. It’s because far more of the vendors in Chelsea, Manhattan, SoHo etc are legal and more or less follow the vending rules. The vendors in the areas like Jackson Hts have a predominance of illegal vendors – no license, no cart permit, a totally illegal food cart and they follow no rules. The Street Vendor Project (SVP) pretends that the increase in enforcement and the seeming “targeting” of their members is somehow unexpected and mysterious OR is a racist conspiracy against minorities. What’s the reality? SVP helped write the vending law (Intro #1116) that put the BIDs in charge of vending; they spent years lobbying for it; they helped put a new agency in charge of enforcement in addition to the NYPD; and they lied to all their members that they would all soon have permits and become legal. It was all a scam by SVP, a City Council funded front group that has done more harm to vendors than any BID or elected official. This website routinely censors any comment that in any way criticizes SVP.

lolol good old Robert Lederman. Love when old white men like you try to invalidate the lived experiences of immigrant New Yorkers. Stick to making art, online conspiracy theories aren’t working well for you.

This is not journalism. This website practices censorship. It is funded by the BIDs and publishes totally false stories on vending that all attempt to hide the damage that the Street Venor Project has done to their own members and to vending. I dare you to print a true story on vending

I complained to the editors and they finally allowed my comments. Thanks

If you want to see lack of control and total disregard for the law, come to Canal street where I live. It is a nightmare of fake merchandise riddled with drug sales. To add racism into this conversation is another example of trying to deflect from the real issue…BREAKING THE LAW…

Here are two actual situations-examples.

A) There is a small grocery store that has been in the neighborhood for decades. The owners are immigrants.

The store has definitely faced challenges in recent years with high rent, crime, and the explosion in ecommerce grocery delivery.

And now, a fruit and vegetable vendor is situated on the corner, a few feet from the store!

B) Several regular supermarkets have closed over the past 10 years, leaving only one regular supermarket. That supermarket also is facing issues of high rent, competition from ecommerce grocery delivery and a new Whole Foods.

And 3 fruit and vegetable vendors are situated in proximity – a block away, both sides and across the street!

How is this fair?

What happens when the supermarket closes and we have nothing?

City Limits – These are real issues and deserve acknowledgment.

Hi Lisa, thanks for this. I agree those are real issues. I’m interested in hearing more about how you’re seeing this impact your neighborhood, if you (or any other readers) want to discuss further: jeanmarie@citylimits.org

The street vendor project has nothing to do with helping vendors in any way. vendors were told that there would be a lot more licences. Of course there wont be any more and the nypd is still enforcing the vending laws. The fines are now huge and designed by the real people driving the anti vendor bus namely the bids who are trying to exterminate immigrant vending.

Hi John – are you a street vendor in New York City?

The Street Vendor Project is a membership based organizations whose mission and directives are designed, voted on, and strategized by our 2,800 membership base of street vendors from across the 5 boroughs. If you are a street vendor, you are welcome to join our organization and work with fellow vendors to decide what you think is best for the community, then work with other vendors to make it happen. Email us at svp@urbanjustice.org to get involved, or stop by our office at 40 Rector Street.

The fines are outrageous and there is more work to be done always, but separate legislation was actually passed earlier this year to cut down fines on a number of street vending violations: Int. No. 2233.

There would be many more licenses, suppliers were informed. There won’t be any more, of course, and the NYPD is still upholding the vending laws.

I see a lot of people complaining and defending the “immigrant” street vendors. i work at store right at Junction BLVD, Jackson Heights, we all are immigrant, my boss also an immigrant rents the store, pays electricity, insurance, payroll, taxes, we sale, teddy bears, toys, luggage, masks, there are 2 vendors, with huge vans, they are legal in this country, also immigrants like me, the open their huge tables, tents that are 30 feet wide, they sell toys, now what race got to do with this picture? Why racism got to be included on any debate, i am an immigrant and doing the right thing, cleaning and sweeping the front of our store, because if we don’t, we get hit with a 150 dollars ticket that the garbage that the vendor (our competitor) left behind. How is that fair? These vendors are running our businesses, they don’t pay rent, electricity, payroll or Taxes.

any questions about racism let me know.

First of all: i am an immigrant. I work at a store owned by an immigrant, we sell toys, teddy bears, luggage, my boss pays rent, taxes, insurance, payroll.

There are a few of street vendors, unlicensed, huge tents I would say over 20 feet wide, selling toys, hats, almost same merchandise we carry, they are immigrants like me and my boss, they come in huge vans, they live behind garbage, cardboards, plastic bags, they use the poor trees to hang their merchandise and actually that goes against the environment. We get tickets by sanitation at $150, for the garbage they leave behind.

How is that fair? How can my boss compete against that? They don’t pay payroll, they don’t pay rent, they don’t pay insurance, they don’t pay Taxes.

Why are you mentioning racism? What racism got to do with this?

We are located at Junction blvd in Jackson Heights, we all are immigrants here, so don’t talk about racism when those immigrants are taking business away from immigrants whom are legally paying taxes and everything else for their businesses. Sorry my grammar is not good since Spanish is my first language.

I hope you don’t delete my comment again.