Legislation recently introduced in the City Council aims to hold companies like Amazon accountable for the toxic fumes emitted from large distribution warehouses in the city.

John McCarten/NYC Council Media Unit

“My zip code should not determine my health and my lifespan,” said southeast Queens resident Crystal Brown at a City Council hearing last week.

Brown says she lives just a half a mile away from a “huge Amazon warehouse,” where she’s subjected to fumes from a constant volume of trucks coming in and out to store and distribute products. The effects of such traffic can be deadly: two air pollutants released by vehicles, ozone and PM2.5, cause about 2,400 deaths per year in New York City, according to the Health Department.

“The traffic there is enormous and it’s 24 hours a day. It never ceases,” Brown said.

But a bill introduced recently in the City Council aims to solve the city’s warehouse truck pollution problem, which disproportionately impacts low-income communities where most of these warehouses are located.

The legislation, known as an “indirect source rule,” would hold companies that operate warehouses above 50,000 square feet accountable for the pollution their vehicles spew, encouraging them to use fewer trucks.

“We think it will make the air cleaner, it will help reduce our climate impacts and help make communities that live near these facilities become better places to live,” said Rachel Spector, senior attorney at the environmental non-profit EarthJustice.

The bill, which was the subject of a Council hearing last week, was received with an outpouring of support from the environmental community, union workers at Amazon, and city officials. Although supporters expect pushback from the e-commerce industry, they say the city is at a tipping point with its warehouse congestion problem.

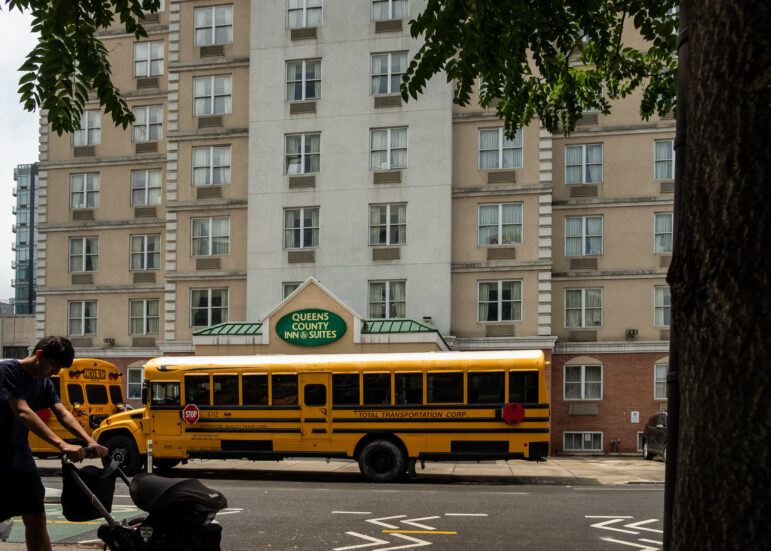

“Suddenly, there’s thousands of cars, tractor trailers and trucks descending on a community that is relatively geographically concentrated and has very limited exits and entrances,” the bill’s sponsor, Councilmember Alexa Avilés, told City Limits.

“What we are seeing are issues of safety, issues of pollution, issues of traffic congestion in ways that these communities have never experienced,” she said.

Compounding effects

E-commerce got a massive boost during the pandemic, and it hasn’t stopped growing since. More than 80 percent of New Yorkers receive at least one package at home each week, according to the city’s Department of Environmental Protection (DEP).

“By 2045, New York is expected to accommodate a 43 percent increase in freight—430 million tons, up from 300 million today,” DEP’s Commissioner Rohit Aggarwala noted in testimony before the Council.

To accommodate that growth and create centralized distribution centers closer to their customers, mega-warehouses began sprouting all over New York. Now, at least one in four residents across the state, a total of 4.8 million people, live within half a mile of a warehouse that is at least 50,000 square feet, according to a January 2024 report by the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF).

Black, Latino and low-income residents live near these warehouses at rates that are more than 59 percent, 48 percent and 42 percent higher than other populations, EDF’s report notes.

In the Big Apple, new warehouses popped up in communities that were already environmentally burdened industrial zones, like Brooklyn’s Newtown Creek and Sunset Park, Hunts Point in the Bronx and Southeast Queens near JFK airport.

“The negative health impacts of air pollution are now even more concentrated in low income neighborhoods than they were before,” Aggarwala said at the hearing.

“Air pollution from traffic alone contributes to an estimated 320 premature deaths and 870 emergency department visits and hospitalizations each year in New York City,” the commissioner added.

Aggarwala believes an indirect source rule will be “a strong tool” for curbing that pollution. And the best way to go about it, he says, is to establish a system that requires companies to earn a certain number of points a year for implementing environmentally friendly solutions to drive down fumes.

That could include using electric vehicles, installing anti-idling technology in existing trucks, or planting trees to offset dirty emissions. This approach follows the model of the indirect source rule that was implemented in Los Angeles in 2021.

Manufacturers, Aggarwala explains, would be able to mix and match from a list of possibilities for reducing emissions and would earn points that are proportional to the number of vehicle trips made to their warehouse. This system, he says, would not only curb pollution but encourage companies to shift to cleaner ways of moving goods around the city, like rail and waterways.

ohn McCarten/NYC Council Media Unit

Councilmember Alexa Avilés, the bill’s sponsor, at a hearing on the legislation last week.Another ‘costly’ mandate?

But not everyone is as hopeful about the legislation.

Zach Miller, vice president of government affairs at the Trucking Association of New York, urged in his testimony that the Council “reconsider” its approach to the indirect source rule “and work toward a more collaborative process that includes all key stakeholders from the outset.” Miller also asked that the rule “be structured in a way that provides flexibility while ensuring practical implementation for all affected parties.”

Osagie Afe, a senior business manager at a group that supports local enterprises, the Long Island City Partnership, fears the rule would be a “burden” to the business community, which is already dealing with other “costly” climate mandates.

Landlords who don’t comply with the city’s local building emissions mandate, Local Law 97, face fines if they don’t reduce their carbon footprint, he points out, and a congestion pricing program imposes charges to enter Manhattan south of 60th Street to reduce vehicle pollution.

“Putting the indirect source rule on top of these challenges risks tipping the scales too far, making it unsustainable for industrial businesses to operate in New York,” Afe said.“If businesses are weighed down by potential fines from this rule, they will struggle to make investments necessary for adopting sustainable practices.”

Advocates of the bill assure that small businesses won’t be impacted as it only covers massive warehouses of at least 50,000 square feet. And they point to how much it will help workers who come in and out of these facilities and are exposed to pollution daily.

“We are on the front lines of Amazon’s environmental injustice,” said Nicholas Kammer, an Amazon driver who led a strike in December against the company’s labor practices. “We spend more time around polluting vans than anyone.”

But Avilés expects companies like Amazon to push back to avoid regulation at all costs and pour money into lobbying groups to block the legislation.

“They have a very strong lobby in New York City. If that were not the case, we would have regulated these things a long time ago,” Avilés said.

“But because people are also seeing the impacts of what is happening in this unregulated space on communities in New York City, we are having a lot more traction.”

To reach the reporter behind this story, contact Mariana@citylimits.org. To reach the editor, contact Jeanmarie@citylimits.org

Want to republish this story? Find City Limits’ reprint policy here.