The Council voted to adopt a modified version of the City of Yes plan—one which scales back some of the zoning reforms included in the original, adds affordability incentives, and allocates $5 billion for infrastructure upgrades and housing programs.

Gerardo Romo / NYC Council Media Unit

Council Speaker Adrienne Adams and other lawmakers at a press conference Tuesday, touting the deal.Editor’s note: The City Council adopted the modified City of Yes for Housing Opportunity proposal on Thursday by a vote of 31 in favor and 20 against. This story has been updated to reflect that.

The City Council voted Thursday to adopt a modified version of the mayor’s City Of Yes for Housing Opportunity proposal—one which scales back some of the zoning reforms included in the original plan, adds affordability incentives, and pledges $5 billion for infrastructure upgrades and affordable housing.

The plan’s passage is a win for Mayor Eric Adams—who is facing federal corruption charges—and comes after a months-long, at-time contentious review process, including a July public hearing that lasted 14 hours. City of Yes for Housing updates a number of decades-old zoning rules to make it easier “to build a little more housing in every neighborhood,” according to the proposal’s tagline.

The changes, officials say, will create an estimated 80,000 new homes over 15 years, more than what was built under both the de Blasio and Bloomberg administrations (though less than the 108,850 the mayor’s office initially projected for the plan). It comes as the city faces its greatest housing scarcity in decades, and record-high homelessness in the last two years.

“The impacts of these housing pressures are profoundly unequal, with a disproportionate effect on Black and Latino communities,” City Council Speaker Adrienne Adams said at a press conference Tuesday. “Our city’s Black community, the population itself, has declined by nearly 200,000 people over the past two decades, a deeply alarming exodus that is attributed to rising costs and the lack of opportunities for families to own a home.”

The Council pushed for weeks to get City Hall to commit capital funding alongside the plan, arguing that zoning reforms alone weren’t sufficient to address the housing crisis. The $5 billion secured as part of the deal up for a vote this week includes money for NYCHA repairs, rental vouchers and infrastructure upgrades to address flooding, among other initiatives.

Lawmakers also negotiated a number of modifications to the plan—in response, they say, to concerns from the community aired during public review. These include affordability incentives for developers of larger buildings in certain neighborhoods, who will have to make 20 percent of their units income-restricted if they want to take advantage of the new allowable zoning.

The revised plan also maintains parking minimums for new development in certain outer borough neighborhoods, and limits some of the places where the reforms would taller buildings in low-density commercial areas and transit districts.

"We believe our modifications to the zoning reforms balance respect for neighborhood character, because not all districts are alike," Adams said Tuesday.

Here's a closer look at some of the changes and what was included in the final deal.

What's the $5 billion for?

The $5 billion commitment attached to City of Yes' passage covers investments in new housing, infrastructure upgrades and tenant protection measures. The funds include $1 billion promised by Gov. Kathy Hochul, pending approval in the state budget in the coming months.

The rest was pledged by Mayor Adams, with $2 billion for affordable housing development and preservation, including for NYCHA and Mitchell-Lama developments, and $2 billion for infrastructure investments to better prepare neighborhoods for more housing, such as upgraded stormwater and drainage systems, street improvements, open space and flood mitigation efforts.

According to the Council, the pot of money includes:

- $1 million for technical assistance for faith-based and community-based organizations that want to build housing on their land as part of the City of Yes reforms

- $1.5 million to support and strengthen community land trusts (CLTs)

- $41 million to expand the HomeFirst Down Payment Assistance Program

- $22 million to support homeowners with property tax and water costs

- An additional $215 million for CityFHEPS rental vouchers during the current and next fiscal years

- $150 million to cover NYCHA rental arrears for eligible households

- Restoring $7.6 million in baselined funding for the Anti-Harassment Tenant Protection program, whose providers saw their city contracts cut at the start of the most recent fiscal year in July. These nonprofit attorneys work with low-income tenants with issues like landlord harassment, illegal rent hikes or compelling building owners to make repairs.

- $3 million for the Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) to design new flood maps, and $608,000 for the development of a new Surface Flood Sensor Program.

- Adding 200 staff positions to the city agencies that work on housing issues, including the Department of Buildings and the Department of Housing, Preservation and Development. The deal also pledges "new attorney positions" at the City's Commission on Human Rights, "to support enforcement against violations of NYC’s Human Rights Law, including source-of-income discrimination." SOI discrimination is when a landlord or real estate broker refuses to rent to a tenant with a housing voucher, a practice which is illegal but widespread. The number of city attorneys working on SOI enforcement had dwindled in recent years.

- $200 million for NYCHA's Vacant Unit Readiness Program, which prepares public housing apartments for the next tenant after a household moves out, and often includes major renovation work, like lead abatement. The number of vacant units across NYCHA has spiked in recent years, in part due to the cost of such repairs; as of October, more than 5,000 apartments across the system were empty.

"I represent the largest public housing stock in the entire city, and continue to be very disappointed by the state of our public housing developments and the fact that we're not doing enough to really help mitigate the day to day issues that our residents are facing," Councilmember Diana Ayala, who represents parts of the Bronx and Upper Manhattan, said at Tuesday's press briefing.

"And by issues, I mean basic necessities like refrigerators and stoves, and patching a hole in the wall and remediating the rats that are coming in now," she said.

Affordability adds

One of the key complaints about City of Yes for Housing is that it didn't include enough incentives for developers to create affordable homes. While one portion of the plan, the Universal Affordability Preference, offers projects a 20 percent density bonus if the extra units are affordable, its use is restricted to medium and higher density districts.

The Council's modifications aim to change that, with affordability incentives added to other aspects of the plan that target lower density neighborhoods. These include the Transit-Oriented Development and Town Center Zoning provisions, which allow three- to five-story residential buildings in commercially zoned areas and near train stations.

Under the Council's tweaks, developers of projects larger than 50 units where those two reforms apply can only take full advantage of the change if at least 20 percent of apartments are affordable, and reserved for households earning 80 percent of the area median income ($111,840 for a family of three).

For the Universal Affordability Preference in higher density districts, the Council added a requirement for "deep" affordability—if a developer wants to take advantage of the additional floor area ratio, it would need to make 20 percent of the affordable units available to households earning 40 percent of the area median income ($55,920 for a family of three).

"I know this seems numbers and wonky, but this is the difference between rents that are $2,500, $2,800, which in the South Bronx nobody is affording, right? Versus units that are down below $1,800, sometimes $1,200 or less," said Barika Williams, executive director of the Association for Neighborhood & Housing Development (ANHD).

The Council also added restrictions to where Transit-Oriented Development and Town Center Zoning changes would apply. The taller buildings allowed under Town Center Zoning would now be prohibited on blocks that are mostly one- and two-family homes, and areas eligible for Transit-Oriented Development would exclude R1 and R2 zoning districts (neighborhoods limited to detached single-family homes).

The Council also reduced the radius where Transit-Oriented development would apply for the city's "outermost" LIRR and Metro North stations, to within a quarter of a mile, down from half a mile in the original plan.

The great parking debate

Adi Talwar

A parking lot in Lower Manhattan.A key sticking point during negotiations over the plan was the removal of parking requirements for new development, which currently apply for residential projects in much of the city (except for Manhattan below 96th Street, and parts of Long Island City).

Critics of the practice say mandating developers to include off-street parking spots to build new housing drives up the cost of construction, though some elected officials and residents, particularly in outer borough neighborhoods, balked at the prospect of doing away with them.

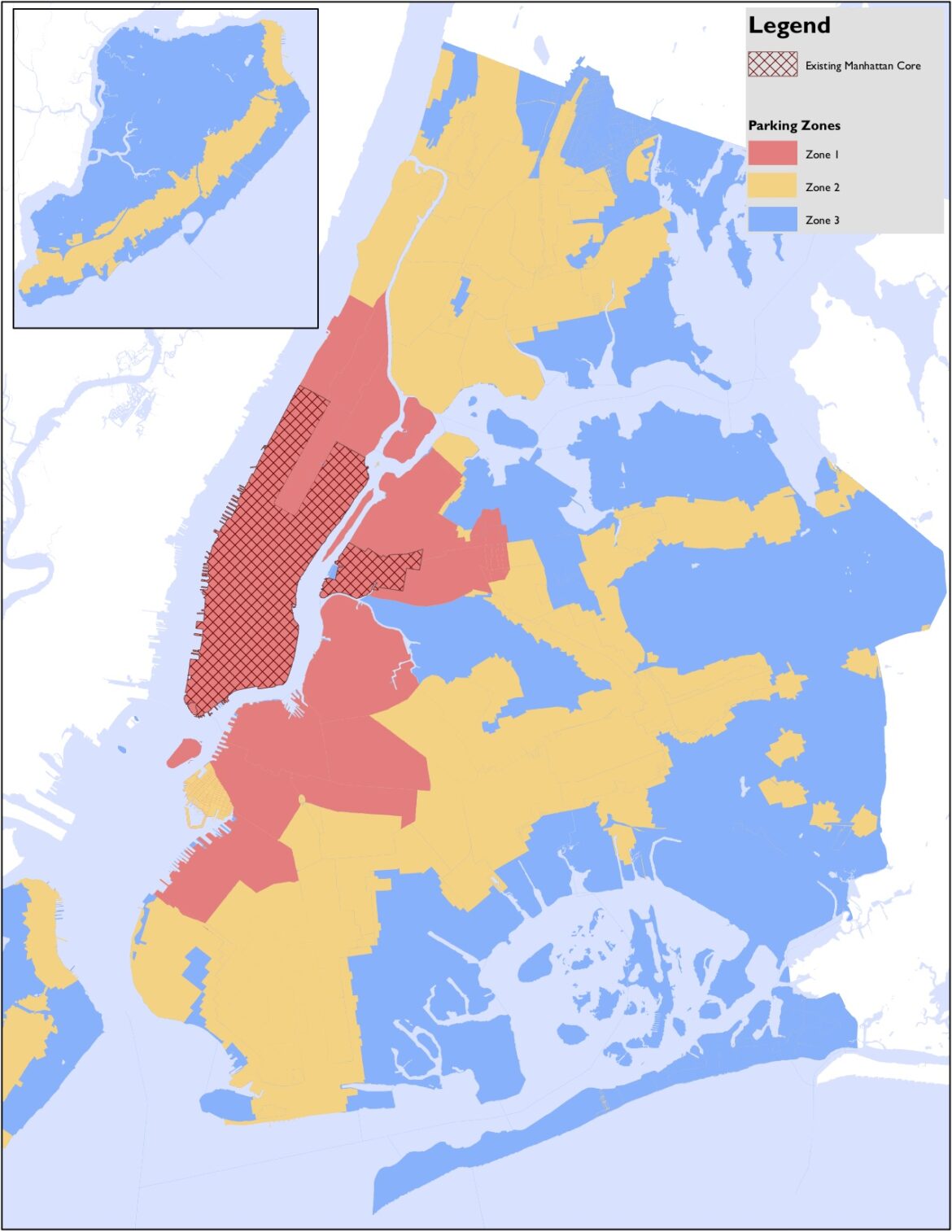

The Council opted for a patchwork of parking rules, creating three geographic zones with different requirements (though certain types of developments would be exempt from the minimums regardless of where they are, including affordable housing, transit-oriented development, Town Center development, Accessory Dwelling Units and conversions).

Deeply transit accessible neighborhoods dubbed "Zone 1" would see parking requirements lifted entirely, "Zone 2" areas would have reduced minimums, while "Zone 3" spots would maintain most of the existing mandates.

NYC Council

Each zone will have different requirements around parking space minimums for new housing.Many transit and open space advocates were disappointed in the shift. Sara Lind, co-executive director at Open Plans, which advocates for more public spaces, called it "an incremental victory."

"While cities across the country are fully lifting parking mandates, the New York City Council chose to be less bold," Lind said in statement. "This was a once-in-a-generation chance and we believe far too many New Yorkers still live in car dependence and transit deserts that are caused in part by parking mandates."

Accessory Dwelling Units, infill limits

Another major change was to City of Yes' reforms around Accessory Dwelling Units, or ADUs. The proposal sought to make it easier for property owners to make these add-ons—independent units on the same lot as existing housing, such as a backyard cottage, converted garage or basement with a separate entrance.

Supporters, which include advocates for older adults like the AARP, tout ADUs as a means for homeowners to house multiple generations of family, or to earn additional income to help them remain in their homes.

The Council's plan adds restrictions. It prohibits backyard ADUs in low density residential areas (R1, R2 and R3 zones, unless they're in a transit-accessible district) and in historic districts. It blocks ADUs altogether in attached homes or row-houses, and those on ground or basement floors if they're in areas vulnerable to flooding. And to build an ADU, the homeowner is required to live on the property.

"By potentially restricting accessory dwelling units and town-center zoning, the council is not just reducing total housing production. They're eliminating housing options that could help seniors age in place and young families remain in their communities," David J. Rosenberg, a land use attorney with Rosenberg & Estis P.C., said in a statement responding to the revisions.

The final City of Yes deal also put some limits on zoning for "infill" housing, which would make it easier for religious facilities, schools and coops to build on their campuses. To address concerns about overcrowding, the Council would prohibit infill on any land being used today for recreation, and require that campuses maintain a certain percentage of open space. It also excludes NYCHA campuses.

Speaker Adams said the revised deal demonstrates "balance."

"We heard voices of community residents who participated in the public review process, including those who are concerned about what City of Yes will mean for their neighborhood," she said at a press briefing Tuesday. "We are showing it is possible to ensure every neighborhood contributes to creating more homes for New Yorkers, while respecting the differences across neighborhoods."

To reach the editor, contact Jeanmarie@citylimits.org

Want to republish this story? Find City Limits’ reprint policy here.

One thought on “What the Council’s Revamped ‘City of Yes for Housing’ Deal Includes”

May I now finally be able to bury my dead in my low density residential backyard? 😉

Good luck to all!