The elimination of parking minimums is part of a zoning text amendment New York City Mayor Eric Adams detailed Thursday, amid a push to increase housing development citywide.

A decades-old regime requiring parking as a part of new residential construction could soon be a thing of the past, Mayor Eric Adams announced Thursday.

The elimination of parking minimums is part of a zoning text amendment the mayor first previewed last June—a broader effort to increase housing development across the city. The entire proposal, presented Thursday in new detail, will go through a multi-step review next spring before landing at the City Council for approval.

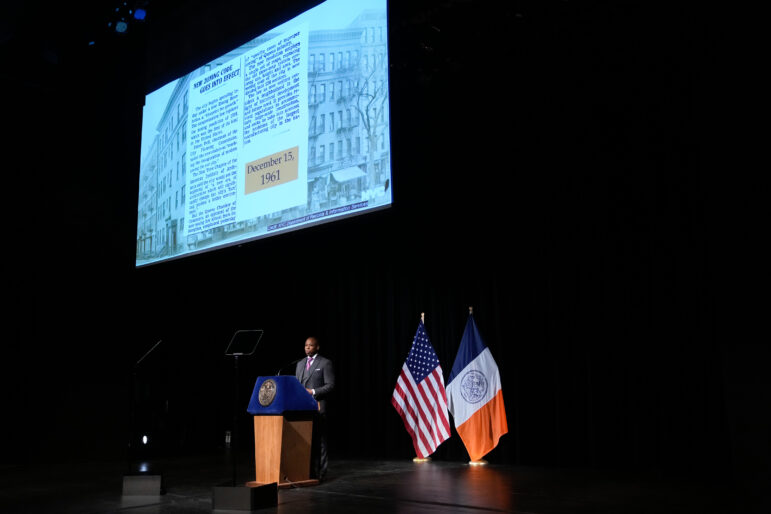

While tax incentives to help spur development are out of the city’s control, zoning reform is not. The proposed amendment aims to change citywide rules on where and how homes can be built that have been in place since 1961.

“This is not tinkering around the edges. This is groundbreaking, literally, by rewriting the wrongs of history,” the mayor told an auditorium of advocates and politicians at Borough of Manhattan Community College.

There is currently a patchwork of parking requirements in New York City, dating back to the 1950s. Generally, these rules require off-street parking to be built with new residential construction. Due to space constraints, parking is usually built subgrade—a costly job opponents say drives up rents.

Exceptions to parking minimums exist in much of Manhattan and near subway entrances citywide. But the rest of the city is generally subject to the rules, ranging from a one-to-one ratio of parking to housing units, down to 40 percent of the unit total.

“We’re going to make housing for New Yorkers, not cars,” Mayor Adams said.

The new “City of Yes” proposal also includes a 20 percent density bonus for affordable housing, though the Adams Administration has yet to provide specifics on how much tenants might have to earn to qualify for these apartments.

The bonus would be modeled after an existing program called AIRS, or Affordable Independent Residences for Seniors, which allows for more housing in projects pitched for neighborhoods that are already relatively dense.

Department of City Planning (DCP) Chair Dan Garodnick told reporters Thursday that he hopes to push deeper than 80 percent of the Area Median Income, or $101,680 for a family of three, but did not name a specific target.

“We’re just starting that process now,” he said. “We believe that we can and should do better than the current 80 percent AMI.”

The proposed amendment would also legalize an extra apartment of up to 800 square feet for one- and two-family homes—a move the city hopes will spur Accessory Dwelling Units, or ADUs, in garages, attics, backyards and basements.

Some of these conversions are expected to be more costly than others.

For example, a 2019 pilot program in East New York revealed that state Multiple Dwelling Law compliance can push the cost of a basement conversion toward $1 million. The law kicks in when a two-family home attempts to add a third unit, and efforts to reform it fizzled during this year’s state legislative session.

“For the Accessory Dwelling Units, we’re going to need the partnership of the state, for sure,” Adolfo Carrión Jr., commissioner of Housing Preservation and Development for the Adams Administration, told City Limits Thursday.

“Last year was our first shot at this,” he added. “I think our second up at bat is going to be a better one.”

Mayor Adams is hoping to reverse a trend in New York City where job growth has outpaced housing production. According to DCP, the city added 800,000 jobs in the decade leading up to the COVID-19 pandemic, and just 200,000 homes.

City Hall predicts the text amendment could allow for 100,000 new units of housing.

“Zoning is a critical piece of the puzzle,” said Annemarie Gray, executive director of the pro-development group Open New York, following Thursday’s announcement. “It is also not everything.”

Her group was a major proponent of a statewide policy pitched last year by Gov. Kathy Hochul that would have required increased development across the state, with the potential for state override if localities failed to build. It, too, fizzled in the face of opposition from near-city suburbs, as well as less dense parts of New York City.

“We need an approach that also recognizes that you need protections for tenants that are facing problems right now,” Gray added. Her group supports a Good Cause Eviction proposal in Albany, backed by tenant organizations and derided by developers, which would expand defenses against eviction and steep rent increases.

The zoning amendment unveiled Thursday would also loosen rules that have made it difficult for landholders like the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA), as well as churches and schools, to use their existing building rights. For example, it would cut a rule that bars construction if any older buildings on a campus exceed height limits.

The amendment would further encourage small apartments with shared kitchens and bathrooms—a Single Room Occupancy model—and allow more height for apartments on low-density commercial strips, as well as areas walkable to public transit.

“We’re trying to eliminate the types of hand-to-hand combat, building-by-building, that we so frequently see in New York City, and to enable growth, a little bit of housing, across all neighborhoods,” said Garodnick of DCP at a press gaggle.

City Council Speaker Adrienne Adams called the proposed text amendment “encouraging and thoughtful” in a statement, adding that the council will do a “thorough review.”

The housing shortage in New York City is particularly acute for the lowest-income renters. Less than 1 percent of all apartments priced below $1,500 per month sit empty, the lowest rate since 1991, according to the 2021 Housing and Vacancy Survey.

Carrión of HPD told City Limits Thursday that his office is working on building more affordable housing at the lower end of the spectrum, though he said specifics are still being hammered out.

Currently, HPD-funded developments serve households earning up to 30 percent of the AMI at the low end, or $38,130 for a family of three.

“We’re working on a set of proposals that will take AMIs—the lowest now is 30 percent AMI, generally speaking—and take it down a few notches from there,” he said.

To reach the reporter behind this story, contact Emma@citylimits.org. To reach the editor, contact Jeanmarie@citylimits.org.

3 thoughts on “Mayor Adams Pitches Zoning For Less Parking, More Housing ”

Not enough. For example why only allow for 2-4 story residential floors above single story commercial buildings right next to commercial amenities and transit in areas with too limited zoning? Way too timid.

Reminds me of the extremely limited rezoning proposals for the few blocks surrounding the coming new Bronx Metro North stations.

Many other global cities are building so much more dense, transit oriented housing and we just aren’t making the more aggressive changes necessary.

Becasue NYC has a limited very old water/sewer infrastructure, especaily in the outer boros where many of these zoning proposals will not be approved by local councilmembers. Upzonimgs are not popular in the outer boroughs to begin with.

The sewage and water infrastructure can be upgraded where necessary. It’s timid politicians and a timid planning as a result. Oppositions to up zonings are typically from a small but vocal minority of neighborhood’s population. Most people here don’t care if there’s more density, but way more do care when they can’t afford housing.

Like it or not, the future of NYC is higher density.