“It has become increasingly clear that the Adams administration has committed to expand a policy of mass incarceration over community services and other less expensive, more effective alternatives. The current administration would have you believe that this is the only option. It is not.”

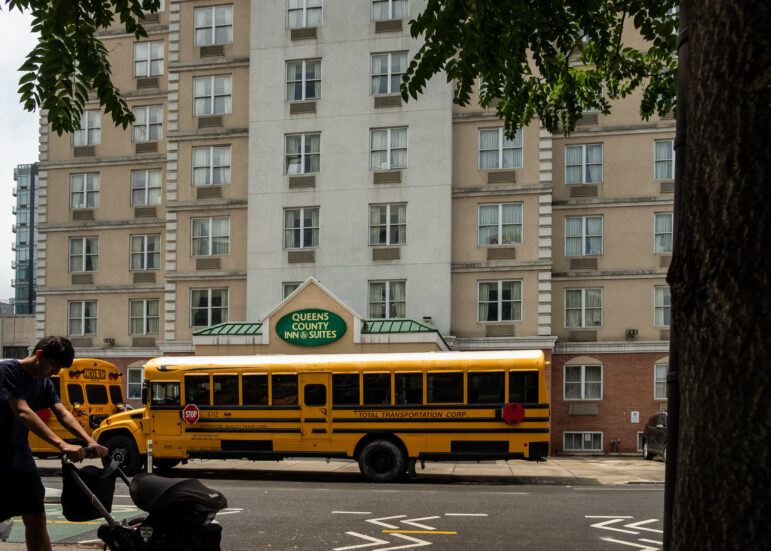

Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office

Mayor Eric Adams at Rikers Island in June 2022.How many women and gender-expansive people does the city of New York plan on locking up? This is the brutal math behind the design of the upcoming borough-based jails, a calculation whose answer is dependent less on mathematical projection than on policy.

It has become increasingly clear that the Adams administration has committed to expand a policy of mass incarceration over community services and other less expensive, more effective alternatives. The current administration would have you believe that this is the only option. It is not.

In June 2022, the “Path to Under 100″ report, released jointly by the Women’s Community Justice Association, the Independent Rikers Commission, the Center for Court Innovation, and John Jay’s Data Collaborative for Justice, detailed a step-by-step process to reduce the population of the Rose M. Singer Center, the facility on Rikers Island where the city currently incarcerates women and gender-expansive people, from roughly 300 to under 100.

The steps were simple and backed by decades of data: Invest in gender-responsive community services like housing and treatment. Provide adequate assessments for mental illness and its role in relevant charges. Establish a population review team.

All of which is to say: this is not complicated.

When the plan to close Rikers Island passed in 2019, it did so hand-in-hand with certain conditions, primary of which was the reduction in the jail population. But as the borough jail plans under Mayor Eric Adams’ influence are revealed, this goal has fallen by the wayside. In Brooklyn, lower-occupancy therapeutic units have been scratched in favor of higher-capacity general housing. And in Queens,the number of beds planned for women and gender-expansive people has more than tripled from the original estimate, from 126 to 450, inexplicably adding an additional three years to the estimated construction timeline.

What could possibly justify a threefold increase in the number of women and gender-expansive people in New York City’s jails? Despite dire and alarmist proclamations, the city’s crime rate has remained relatively stable for the last decade.

Furthermore, New York City has successfully reduced its jail population before. For nearly three decades, a declining jail population was accompanied by increased community safety. During the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, the jail population was reduced substantially and rapidly, with no significant attendant rise in crime or pre-trial flight. During this period, the population at the Rose M. Singer Center dropped below 150 people, well within range of the 126-bed capacity of the original Queens borough-based jail plan.

All of this raises further questions, first among which should be: Who will be occupying those additional cells? Eighty percent will have mental health concerns. Seventy percent will be primary caregivers. The overwhelming majority will be held awaiting trial—not because they are particularly dangerous, but because they lack the resources to scrape together cash bail.

Queer and transgender incarcerated people experience disproportionately high rates of homelessness and unemployment, both of which are linked to higher rates of criminalization. And both women and gender-expansive people are more likely to be survivors of intimate-partner violence. They’re also extremely vulnerable to sexual violence at Rikers, as recent reports have shown.

This isn’t just a matter of efficacy, but of budget. The cost of incarcerating one person at Rikers Island for a year is around $507,000. The Women’s Community Justice Project has successfully provided an alternative to detention program, along with housing, for women who would otherwise be kept at Rikers, for approximately $65,000 per year. So, the cost of incarcerating one person at Rikers Island could provide supportive housing for eight.

That the city has jumped to increase jail capacity before attempting to implement any of the report’s recommendations is a betrayal of the trust and human rights of its most vulnerable citizens. It is socially irresponsible, financially unsound, and inexcusably cruel.

It’s easy to pin this all on the Adams administration, but it’s equally important to understand that what we are seeing play out in real time is the story of mass incarceration in New York City. It’s the story of the Women’s House of Detention, and subsequently the New York City Correctional Institute for Women. It’s the story of the Rose M. Singer Center, whose nursery and other amenities were sacrificed in development to make room for more beds.

In short, New York City has never seen a human right that it wouldn’t trade for the capacity to cage more women. And this must change.

We call on our elected officials to do the right thing and rise to the promise of decarceration by shoring up community-based services and alternatives to incarceration, ensuring strong implementation of the jail population review initiative, and rejecting the easy cynicism of caging more of our neighbors.

The closure of Rikers should be a huge positive step towards a safer, more humane New York. We can’t let the mayor unravel its promise.

Jay Edidin is the director of advocacy at the Women’s Community Justice Association.

One thought on “Opinion: NYC Must Live Up To Its Decarceration Promises”

Great article, Jay!