Legal problems have plagued the city’s massive school food system, but still haven’t derailed a decades-long local campaign to use New York City cafeterias to fight hunger, improve nutrition, reduce social inequality and support learning.

Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office

Last month, a federal judge sentenced a former New York City school food official to two years in prison for taking bribes from a contractor—an arrangement that resulted in kids eating tainted chicken, a school staffer choking on a bone and another chapter in the complex history of school nutrition in the five boroughs.

On one hand, the conviction and sentencing of Eric Goldstein, the one-time CEO of a food system that serves nearly a million kids and is second only to the U.S. military in size, is not an aberration. For nearly 30 years, the city’s school food program has been periodically tainted by quality concerns, management lapses and criminal convictions.

At the same time, the program’s legal problems have not derailed a decades-long local campaign to use New York City school cafeterias to fight hunger, improve nutrition, reduce social inequality and support learning—all of it on the federal government’s dime.

These nuances are especially important now. Eric Adams, a champion of more nutritious school eating, could lose the mayoralty because of an entirely separate set of corruption allegations. A new schools chancellor is taking over amid the administration’s turmoil. Meanwhile, nutrition advocates are holding up New York City as an example in a campaign to provide universal free lunches statewide.

Local origins, national support

The notion of providing meals in schools dates back at least to mid-19th century Europe. In New York City, school food began in 1853, when the Children’s Aid Society launched an industrial school and offered meals as a way to entice low-income students to enroll.

Broader efforts took root elsewhere in the Northeast: Private philanthropists and public officials in Boston, for instance, developed a system for providing food to multiple schools around the turn of the century. It was during the Great Depression, when school lunches provided an elegant solution to the dual problems of childhood hunger and agricultural surpluses, that national school nutrition efforts began, and continued through World War II.

Despite opposition from those who saw it as part of a communist plot or a threat to racial segregation, Congress passed the National School Lunch Act of 1946 to formalize the system that exists today, in which the federal government reimburses schools for meals that adhere to basic nutritional guidelines. Later federal legislation authorized expansions like the school breakfast program, although states were sometimes slow to sign up for the new offerings: Albany didn’t approve school breakfasts in New York until seven years after the feds started dangling money for it.

According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, some 236 billion school meals were served nationwide from 1969 through 2022. USDA says about 60 percent of eligible students across the country get school meals, a drop from earlier years. Nutrition advocates have tried to increase that rate, but have been stymied by stereotypes of school food as bad-tasting and unhealthy and by the cultural stigma surrounding “free lunch.”

City schools now serve about 850,000 meals each day. School breakfast has been free for everyone since 2003 and lunch since 2017—measures adopted in order to reduce the stigma around school food, and to earn the city the maximum rate of federal reimbursement per meal. City schools also offer after-school meals and summer food, and during the worst days of the COVID-19 pandemic, anchored a massive effort to distribute free food to New Yorkers of all ages.

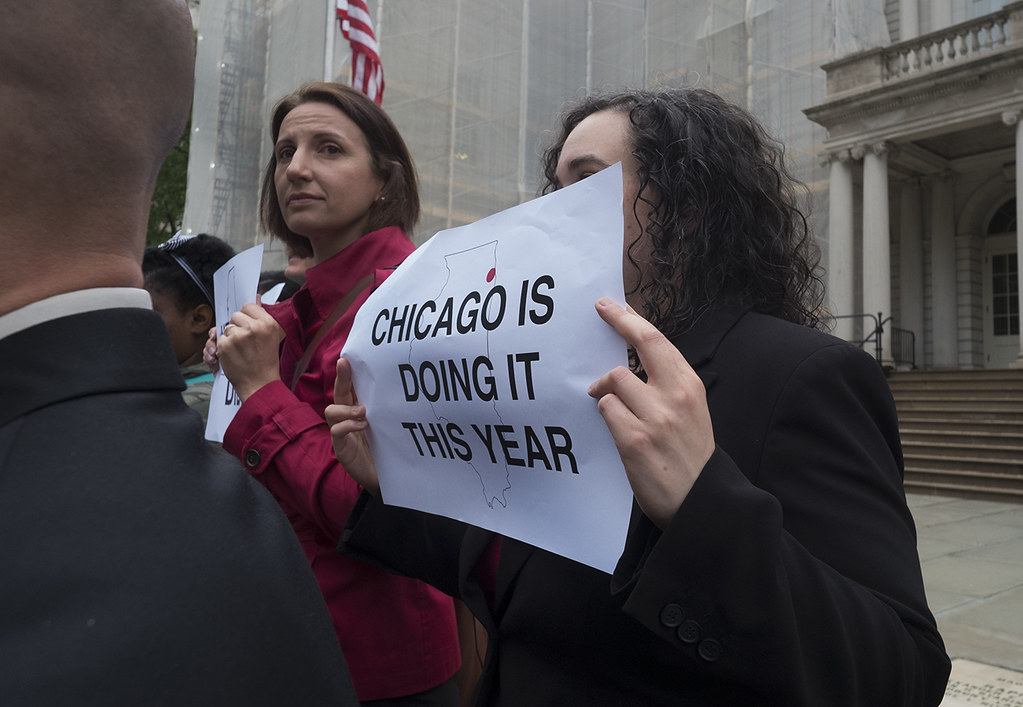

William Alatriste for the New York City Council

A 2014 rally calling for the city to adopt free universal school lunches. It did so in 2017.In the 2022-2023 school year, the city spent $576 million on school food, split pretty evenly between salaries for staff and payments to the private companies who produce or deliver the meals to schools. Federal and state nutrition aid to the school system totalled $645 million. However, doubts about the extent of federal support triggered a mini-crisis earlier this year when the Adams administration cut $60 million from the school food budget and removed several popular items from cafeterias, only to restore them a few months later.

The system is massive and intricate, involving the purchase, shipping, storage, preparation and serving of hundreds of different food items by 1,700 unionized employees in nearly 1,500 schools. They operate under nutrition standards that exceed those set by the federal government, and provide meals to arguably the most diverse student body anywhere in the world during the jam-packed modern school day.

It is perhaps not surprising that there have, at times, been issues.

Serving up scandals

In 1992, 42 kids got sick from tainted spaghetti at Public School 306 in Brooklyn. Three years later, the school system’s special commissioner for investigation found that “large amounts of donated food stored well past recommended shelf lives was being served to children in school cafeterias,” with some turkey still in warehouses a year after it was supposed to be thrown out, and 28 out of 55 samples of school food found to be rancid. The schools chancellor reassigned three top school-food officials after that report, but the top executive managed to hang on to his job for another seven years.

Federal prosecutors indicted 30 people and 14 companies in 2000 for rigging bids covering $210 million in school food between 1996 and 1999. “The conspirators held secret meetings where they agreed to carve up future bids to supply and deliver frozen food to the schools,” according to a Department of Justice statement at the time. “The conspirators agreed on the geographic zones that each participating company would win and lose, and also agreed on the prices or price levels they would bid. In addition, winning bidders secretly shared the profits on certain bids with the losers.” At least 13 people went to federal prison for the scam, and courts ordered $30 million in fines and restitution.

Yet, four years later, a city investigation found that two school-food officials had taken improper gifts from vendors and, perhaps as a result, contracts were written in a way to favor a particular food company—a firm linked to one of the figures who went to prison in the 1990s scheme—and others “to reap profits far in excess of what they should have earned.” The investigation cited “obvious weaknesses in the bidding procedures” even after the massive federal indictment should have signaled the need for reform.

The system encountered a different set of problems during the Bloomberg years. A consulting company advised the administration to streamline the way food was transported to schools, cutting the list of delivery firms from a dozen to just three. While the move promised efficiency on paper, in practice it was a disaster during the 2004-2005 school year, leading to delivery delays, food shortages and steep fines against the delivery firms. The DOE had to declare an emergency and bring in other vendors to reset the system.

There were indications of trouble even after the turmoil of the early 2000s. The comptroller’s office found in one 2011 audit that there were weaknesses in the DOE’s system for dealing with food contractors, which resulted in “unsupported payments to distributors” and overpayments. Another audit 10 years later discovered that, from 2015 through 2018, the DOE “spent more than a half-billion dollars, averaging $134,585,721 per year, on scores of food products called ‘approved brands,’ with no competitive bids or proposals, no published rules or procedures, no transparency, and little if any oversight.”

“The noncompetitive and opaque approval process,” the audit continued, “was extraordinarily vulnerable to abuse.”

Bones, metal, plastic and bribery

That was an understatement: By that point, federal prosecutors had charged former DOE School Support Services CEO Eric Goldstein along with Blaine Iler, Michael Turley and Brian Twomey—three officials at a food company called Somma that sold chicken to the DOE—with crimes including bribery, extortion and fraud.

In order to entice Goldstein to keep ordering Somma chicken for school cafeterias even after plastic and metal were found in some pieces on kids’ plates, the Somma executives made payments of more than $96,000 to a separate company, Range Meats, in which Goldstein held an interest. In one particularly egregious episode, after a DOE employee choked on some supposedly boneless Somma chicken that contained a bone and the product was briefly suspended from cafeteria shelves, Goldstein approved the restoration of Somma’s poultry—a day after the other defendants sent nearly $67,000 to a Range Meats bank account.

Goldstein and the other men pleaded not guilty but were convicted last year and sentenced in September, Iler to 12 months, Twomey and Turley to 15 months each, and Goldstein to two years in federal prison. All four have appealed their convictions and sentences.

In response to Goldstein’s conviction last month, the DOE said it had implemented several reforms to prevent a repeat of the Somma scandal. One was to separate the people who create menus from those who find the vendors to supply food, so that the relationships between vendors and their DOE contacts don’t influence decisions about the kind of products school cafeterias need. Another was to involve more field staff in creating the menus. DOE says it also increased the level of outreach to new vendors.

In a statement to City Limits, DOE Spokeswoman Jenna Lyle said, “Everything we do is in service of our children and our families—a sentiment that is championed by our food service and operations teams. We are immensely proud that all our school meals not only meet, but exceed, USDA food standards, and are created with and in ongoing response to student feedback. We have also implemented strong compliance measures and oversight for all menu development and food purchase processes. Our students deserve nothing but the best, and at New York City Public Schools, we work hard in pursuit of that goal.”

Goldstein’s attorneys did not respond to a request for comment.

‘The best moment we’ve ever seen’

Advocates whose passion is reducing hunger take a longer view of school food than the current scandal, and a broader one than the periodic episodes of mismanagement that have dogged the program for more than three decades. In a city where one in four children experiences food insecurity, and where the child poverty rate of 25 percent is double the national average, school food is an indispensable tool for chipping away at a cluster of problems: hunger, inequality, obesity and the ways those issues can impair a child’s ability to learn.

With that perspective in mind, Liz Accles, director of Community Food Advocates, does not believe Goldstein’s conviction says much about the state of school food in the city. “I think we are at the best moment we’ve ever been,” she tells City Limits.

“On the city level we had to fight like hell to get universal free school meals under the de Blasio administration, so that was a very significant shift,” she adds. “I think in New York City we’ve seen the beginning of an elevation of school food and its importance and potential shining through, and becoming a strong point of advocacy, and for elected officials and policymakers to pay attention and invest.”

De Blasio’s move to make school lunch free for every student was a long-sought goal of food justice advocates and, according to Accles, it has paid off. “We’ve heard from younger students that have had universal all their lives that they don’t have the stigma in the same way. So it’s encouraging.”

John McCarten/NYC Council Media Unit

Students participating in the city’s free summer meals program in 2022.Adams, whose personal narrative as a mayoral candidate included a radical change in his relationship with food, comes in for particular praise from advocates for supporting efforts to get healthier foods into schools and directing hundreds of millions in capital funding to update school cafeterias. “In my 40 years experience, this is the best administration,” says veteran school-food advocate Agnes Molnar.

From 2017-18 to 2022-23, the most recent school year for which statistics were available, the average daily number of school lunches served fell 14 percent—but overall school enrollment dropped by about the same amount. All in all, slightly more meals are being served per student than was the case a few years ago. Participation has hovered at around 60 percent, a figure advocates believe can be improved by making it easier for kids to get school breakfast, which is often hampered by a lack of time, staff or space for a morning meal.

If school surveys are to be believed, school food is not universally admired: In the DOE’s systemwide 2024 survey, only 40 percent of respondents said they liked school-lunch menu options—the third-lowest grade DOE received among the 79 questions it asked parents and students. As any parent knows, getting a kid to like what’s on their plate can be tricky. For a system that serves nearly a million kids spread across hundreds of square miles, and has to meet rigid ingredient restrictions under tight cost constraints, it’s even trickier.

“New York City schools are definitely a leader in school nutrition. They operate under some of the strictest standards,” says Jennifer Cadenhead, executive director of the Laurie M. Tisch Center for Food, Education & Policy at Columbia. Those standards include bans on artificial coloring and salt content, as well as initiatives to source food locally and sustainably. Meeting those requirements while also providing food kids will actually like and eat “is always a challenge,” Cadenhead says.

“A lot of the kids are not used to healthy food because food availability is based in part on where you live, and there’s still a lot of neighborhoods without a lot of access. You kind of want to eat what you are used to eating,” Cadenhead adds. Advocates say DOE gathers a lot of feedback on menu items and is always adjusting in pursuit of the right balance between health and popularity. There’s a move to encourage more scratch cooking in schools.

“There’s always a balance with school meals, a dynamic tension,” says Accles. “You want to offer good, appealing food but you want kids to eat it. That’s a healthy tension. What they’re putting real resources and effort into is how do you do that in a way that engages students.”

For now, the primary focus for school-food advocates is on Albany. With federal support, school districts around the country—including throughout New York State—embraced universal school lunch, but when the health emergency passed, most of those programs lapsed. Accles and her allies are lobbying state policymakers to make universal school meals permanent across the Empire State.

Eric Goldstein, meanwhile, is also looking upstate: The federal judge who sentenced him recommended that, if Goldstein’s appeal fails, the former school-food CEO should serve his time at FCI Otisville in Orange County.

To reach the editor, contact Jeanmarie@citylimits.org

Want to republish this story? Find City Limits’ reprint policy here.