Advocates worry that the reinstated rules will inevitably lead to some New Yorkers losing the aid they rely on to make ends meet, especially in the face of a steep rise in the number of people getting the assistance—alongside increased bureaucratic hurdles for recipients since the pandemic began.

Adi Talwar

The exterior of a former benefits center in the Bronx, where New Yorkers can apply and receive assistance with their public benefits cases.New Yorkers who receive cash assistance from the city are navigating the return of pre-pandemic eligibility requirements, where most recipients must participate in work, study or training programs for a certain number of hours each week in order to get benefits.

The “mandatory engagement” rules, which resumed on July 28, were suspended for the last four years after being waived during the COVID-19 lockdown. City officials say they pushed back on reinstating the requirements for as long as possible, but were forced to resume them under state and federal law.

Those who do not comply may face sanctions that could put their benefits on hold, and affect other types of assistance they receive, including housing vouchers and food stamps. No one has been sanctioned yet to date, according to the Human Resources Administration (HRA), which administers cash assistance and began phasing the sanction procedures back in this August.

“We have focused on ensuring clients are not surprised by the end of the pause, communicating with clients ahead of time about the re-imposition of engagement requirements and the potential sanctions we would be required by law to impose,” HRA Administrator Scott French testified at a City Council hearing last week about the change.

“Within the sanction process, we offer opportunities for individuals to come into compliance with the requirements or alternatively, clients may supply an explanation of the factors that prevent their meeting the work requirements,” and avoid losing access to their benefits, he added.

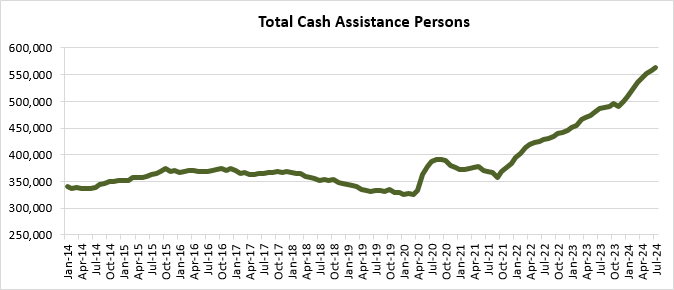

Still, advocates worry that the reinstated rules will inevitably lead to some New Yorkers losing the aid they rely on to make ends meet, especially in the face of a steep rise in the number of people getting the assistance—alongside increased bureaucratic hurdles for recipients since the pandemic began.

Some 557,600 people were receiving cash assistance at the end of June, up 16 percent from the year before and up even more significantly since fiscal year 2020, when just more than 378,000 New Yorkers were enrolled.

The number of people receiving SNAP, or food stamps, also reached a historic high, and both programs have been plagued by bureaucratic problems over the last few years, including substantial delays in the city’s ability to process applications on time.

Human Resources Administration

“The return of work requirements is going to lead to people losing their essential benefits,” said Adriana Mendoza, benefits supervisor at Urban Justice Center’s Safety Net Project. “Families will face eviction and struggle to put food on the table, and later they will face the uphill battle to get their benefits restored.”

Cash assistance includes both larger, one-time grants for emergency needs like rent (also known as one-shot deals) and small, regular payments for the lowest-income New Yorkers, which vary depending on income and household size but max out at $183 a month for single adults and $389 for a family of three, including dependent children.

“People will be forced to work in exchange for measly cash assistance benefits that no one can survive on, and that work won’t increase their future job opportunities or even give them meaningful training,” Mendoza said.

City officials defended HRA’s career services offerings at the recent City Council hearing, outlining a bevy of programs intended to help recipients find work and achieve financial self-sufficiency. They include CareerCompass, aimed at adults 25 and up, YouthPathways for young adults aged 18-24, and CareerAdvance, which aids people looking for employment in specific industries, including New Yorkers with limited English language proficiency.

“There is a universe of city workforce development and career service programs, including HRA and our partners,” French told councilmembers. “Collectively, we stand ready to assist job-seeking New Yorkers.”

In fiscal year 2024, which ended in June, HRA helped approximately 8,100 clients obtain jobs, 12 percent fewer than the year prior, according to the latest Mayor’s Management Report (MMR)—a dip the agency attributed to “a pause in referrals to voluntary employment activities as the Agency prepared to resume New York State mandated activities.”

At the same time, however, the percentage of clients who found work and maintained that employment or didn’t return to cash assistance increased: 74.7 percent of cases did so for at least six months, compared to 69.3 percent the year prior.

The city also saw improvements this year in its processing times for both cash assistance and SNAP: HRA promptly processed 42.4 percent of cash assistance applications in the fiscal year that ended in June, and 63 percent in July—up from a dismal 28.8 percent the year before.

For food stamps, the agency processed 65.1 percent of applications on time, or within 30 days, during the most recent fiscal year, and 87 percent in July, according to the MMR and an agency spokesperson. That’s up from a low of 39.7 percent the previous fiscal year.

Still, the rates remain well below HRA’s targets, and processing delays can have a significant impact for beneficiaries.

Diana Ramos, 47, is a Bronx-based volunteer activist with the Safety Net Project, as well as a cash assistance and SNAP recipient. Her SNAP was due for recertification recently; she submitted her materials on time, and said she was told to expect her benefits to come through on Sept. 5.

But she didn’t receive them until nearly a week later, on the 11th—a wait that she said was likely shortened by the fact that she had a case manager advocating on her behalf to speed things up.

“I was a little bit prepared this year, I made sure to have a little extra of everything,” she said, anticipating a gap based on past experiences with recertification delays. “But you can only eat so much rice as a diabetic, and last weekend, I literally lived off a pack of hot dogs and hot dog buns. I used most of my cash assistance on trying to get food.”

HRA has attributed delays to the significant increase in public benefit applications since 2020, and to efforts the city has made that made it easier to apply, including its online application process and the ability to conduct on-demand interviews by phone (though applicants have complained of extremely long wait times).

“We’re not where we want to be, but we have improved in both” cash assistance and SNAP processing times, Anne Williams Isom, Deputy Mayor of Health and Human Services, said during a press briefing Monday. “We will definitely make more progress.”

At last week’s Council hearing, French said HRA has brought on 1,000 new staffers over the last year to help keep up with demand.

Susan Welber, supervising attorney at The Legal Aid Society, said the organization will be monitoring whether HRA’s staffing adversely affects the reimplementation of work requirements.

“Such shortages have been driving application and recertification delays, among other problems, for the past few years,” said Welber. But she said there are better safeguards in place now to help recipients meet the mandates and reduce bureaucratic errors, compared to before the pandemic.

“Now the law contains stronger preventative measures that will help prevent sanctions from occurring in the first place and will enable clients to resolve the sanctions that do occur very quickly,” Welber said.

“None of us want to see our clients go back to the time when they faced sanctions despite making every reasonable attempt to meet the agency’s requirements.”

To reach the editor, contact Jeanmarie@citylimits.org.

Want to republish this story? Find City Limits’ reprint policy here.