The city’s social safety net has stretched to address the economic disaster created by the pandemic. It might have further to go.

Adi Talwar

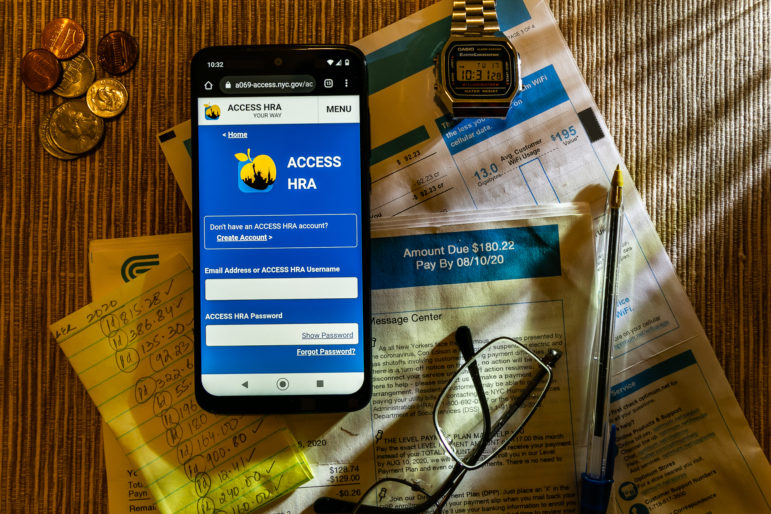

The HRA’s app that allows residents to apply for benefits online has been a convenience for many and a challenge for others, as applications for the city’s cash assistance program have soared during the pandemic.When the financial crisis hit a dozen years ago and human need metastasized through the country, Washington offered states and cities a chance to provide more help to their residents: a waiver of federal law to allow able-bodied adults to get food stamps even if they had hit the three-month time limit. The extra assistance, which would be almost entirely federally funded, would inject cash into neighborhoods knocked low by unemployment and foreclosure—places like Red Hook, East Harlem and Far Rockaway. Many governors and mayors accepted the extra help. Mayor Michael Bloomberg refused.

In the face of an even greater human and economic crisis this year, the de Blasio administration has pursued a very different strategy.

Applications for cash assistance—a.k.a. welfare—jumped 53 percent in March 2020 compared with March 2019, and soared in April as well. The rolls have grown steadily since then, leaping 20 percent between February and September.

This increase was facilitated by strategic decisions early in the de Blasio administration to build a more robust safety net for New Yorkers, as well as by the Human Resources Administration’s real-time response to the unique challenges of the pandemic.

“Leadership at the HRA is well aware of the hugeness of the need right now and that it’s very extensive. A lot of people lost their jobs; some of them are getting unemployment insurance, and for some people that is enough and for others it’s not,” says Cathy Bowman, an attorney at Legal Services NYC. “We’re seeing people who never had to apply for benefits before apply for them now.”

Against the scathing critiques of the de Blasio administration’s handling of COVID-19, the performance of the welfare system poses a stark counterpoint. “They definitely want it to work. They are working really hard,” says Legal Aid’s Kathleen Kelleher. “The vast vast majority of HRA workers are working from home. It’s a really strange situation right now. You’re on the phone with them and a client, and you hear their own kids in the background. To be honest with you, it’s amazing anything is working.”

It’s a testament to the scale of the current emergency that despite what advocates agree are sweeping efforts by HRA to address the deprivation caused by this crisis, there are still needs going unmet.

“They have made large efforts but they also are a very large organization and trying to expand at this rate, especially with people working remotely, is a challenge,” Bowman says. “We are still seeing people struggling to get their benefits.”

Welfare has soared in New York since COVID hit. But the economic devastation still eclipses it.

Groundwork laid

When Bill de Blasio became mayor, he appointed Steve Banks to lead HRA, the agency that oversees the city’s social benefit programs. As a public-interest lawyer, Banks had for years wrestled with the Giuliani- and Bloomberg-era HRA over its treatment of low-income people. When he arrived at HRA’s headquarters at 180 Water St., he brought a new philosophy.

“We demonstrated for the first six years of our work here that you could reform the way benefits are provided to clients and cut in half the number of fair hearings [over benefit disputes] and cut in half the number of sanctions” when people lose their benefits, “and actually the case counts went down,” Banks says. Banks’ reforms involved getting waivers from the state to put applications for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), the program formerly known as food stamps, online. HRA was trying to do the same for cash assistance when the pandemic arrived, so it had an online application system already in development.

“We finally got the waivers from the state when the pandemic hit,” Banks tells City Limits. “So, literally, within days we stood up a system of clients being able to apply for cash assistance and for one-shot rent assistance payments online. Within days we brought cash assistance into the 21st Century. We managed a historic increase in the number of applications.”

Serving more clients online with the new AccessHRA system dovetailed with Banks’ desire to allow as many HRA workers as possible to work from home for health reasons. While Banks and his closest aides have continued to work at HRA headquarters and a handful of neighborhood HRA offices (or “job centers”) are open, the vast majority of the agency’s 15,000-member workforce are working remotely. That required creating a computer system to support that work, training workers to use it, and reassigning 1,300 back-office workers to provide frontline services. One HRA facility was converted to an assembly line for putting together the laptops home-based staff would need.

Stephen Levin, a Brooklyn councilmember who chairs the Council’s General Welfare Committee, believes the reforms HRA undertook before the pandemic were critical. “I do give this administration credit for the long-term work they put into AccessHRA. I couldn’t imagine what it could have been like if there was not AccessHRA available. And it’s a usable and functional program,” Levin says. “I think that’s been a lifeline.”

Banks has held a conference call with advocates just about every week since the crisis began, “trying to keep people in the loop,” according to Bowman. The commissioner believes some of what HRA has done since March could serve as a national model: Over the past eight months, more than 80 percent of cash assistance applications have been done online.

However, Banks acknowledges that the problem is still bigger than HRA’s response to it. “We’re certainly not perfect any day of the week,” he says. “There is tremendous suffering out there. There is tremendous need. No city in the U.S., no state in the U.S., can address what is a generational economic reckoning.”

Apps and downs

The truism of life amid COVID-19 is this: For those who operate comfortably online, things are relatively easy—maybe even better than before. For others, not so much.

This is true of AccessHRA as well, advocates say. “For people who have computers and smartphones and are computer savvy it is a system that works for them,” says Bowman. “The most vulnerable people are the ones who struggle with it the most: the elderly and disabled and the poorest people who don’t have smartphones and always use the library to use computers don’t have a way to apply through an app.”

Seniors and people with disabilities are prone to struggling with the app, and language barriers also exist, advocates say. Even when the app works, the process of gathering and submitting the required documents—pay stubs, rent receipts, bank statements—can be difficult for people without printers, scanners or fax machines at hand.

The problem is not that AccessHRA is a bad app; it’s just that apps have limits. “For people who have challenges with technology, I’m not sure there would be any system that would be easy for them,” says Paula Arboleda, a deputy director at Legal Services NYC. “It’s like me walking my mom through some mishap on her phone. Every step takes an hour. This is not a long-term solution for a significant portion of the population.”

Kelleher recalls one client—a mother who had somehow supported five children on a McDonald’s salary, but had to have an emergency C-section for her sixth child and needed income support. “She had a smartphone. But she could not do it. Part of it was a language barrier,” Kelleher says. She was able to get the woman a phone appointment, however, and benefits were established.

Indeed, for those who strike out online, HRA offers a telephone Infoline. However, “getting through to them by phone is almost impossible,” Bowman says. Advocates detail a myriad of frustrations: callers spending long periods on hold only to be disconnected; long waits to talk to staffers who cannot answer one’s questions; call-backs that, if missed, force callers to start the process again. In August the Safety Net Project at the Urban Justice Center reported that in an informal audit of 98 calls to the hotline, 58 percent were dropped. “In addition to dropped calls, we also documented significant issues with language access, uninformed workers, and confusing menus,” the report contended. “Overall, the Infoline was found to be ineffective.”

If the app and the hotline cannot solve a client’s problem, “the only option is to go into a job center and only seven are open,” Keller says. “Nobody wants to encourage clients to do that because it’s not safe.”

The bigger number out there

Banks acknowledges that the hotline has been a weakness in the tools HRA applied to managing the COVID crisis. “Our Infoline system was never intended to be able to manage this kind of historic increase,” the commissioner says. “The ability to create a brand-new system in recent months to handle Infoline calls from [staffers’] homes was never a system that was imagined.” Citing “constructive input” from advocates, Banks says HRA has moved to retrain staff and will be employing improved technology soon.

The huge increase in the welfare rolls suggests that, for many thousands of households, the system has worked. “All that is true,” says Jack Newton, another Legal Services attorney. “But no one really knows the numbers of people who haven’t been able to access it or the number of people who haven’t gotten through the process.” Attorneys say the most difficult cases can take three months or longer to resolve. Particularly prone to delays are cases where undocumented parents, who are ineligible for benefits, have U.S. citizen children who ought to qualify. “We’ve seen so many first time applicants and for them the process is stunning and soul killing,” Newton says, and some do give up.

The concerns do not stop with new applicants: People receiving cash assistance must regularly re-certify their eligibility, a process that is time-consuming and difficult under the best of circumstances. When the pandemic struck, recertification deadlines were reset. But now the clock has started again and advocates say there is confusion among clients. “Recertification was pushed back, but people still get notices about recertifying. They get notices that they have to come in to a center,” Bowman says. Newton contends that HRA “has absolutely sent out incorrect recertification denials throughout this process.”

Fortunately, the number of people with cash-assistance cases who are “in sanction,” meaning their benefits have been cancelled or curtailed because they violated program rules, is sharply lower these days: Only about 2,300 households were receiving sanctions or in the sanctions process in early November, compared with 11,600 at the same time last year.

State and feds play big roles

Many policy decisions involving welfare are not HRA’s to make. The state Office of Temporary and Disability Assistance (OTDA) sets many program rules. “They have to get everything approved by the state,” says Kelleher. “So it’s not like they can change everything they want to.” Newton concurs: “OTDA is not known for speedy help. HRA will at least fight with us. With OTDA, it’s like screaming into a canyon.” OTDA did not respond to an inquiry. Banks, however, says the state has been a cooperative partner. “Some weeks we were requesting dozens of waivers and the state has been responsive,” he says.

At its core, welfare is a federal program and its underlying structure creates many of the obstacles families encounter when trying to use it. “The value of the cash benefits has dramatically decreased over time. It is times like this that the lack of a real, cash-based safety-net system becomes tragically apparent,” says Liz Accles, executive director of Community Food Advocates.

Eligibility rules that require very low assets, for instance, mean that families can’t rely on welfare to avoid a devastating crisis, only to manage it. “You really have to make yourself become poor to be eligible for these programs,” says Bowman.

The structure of the program feeds the brutal application process. “The most frustrated I’ve ever been is trying to help someone apply for a cash-assistance case and being absolutely flummoxed by how difficult it is, by how opaque it is,” Levin says. “I don’t necessarily think that it’s all the city’s fault. A lot of it is the result of the ’96 welfare reform.”

Add to that the fact that the administrative infrastructure of the city’s social programs has been underfunded, and it is remarkable that the welfare system has responded as well as it has to the intense need generated by COVID-19.

“While we have been able to improve access to benefits by building on the technological improvements we started before the pandemic, we haven’t been able to get federal or state waivers from the basic eligibility requirements for the programs,” Banks says. Low benefits have been a hallmark of federal social programs since their advent. And the asset test, Banks says, “is clearly a problem for people who are going to be episodically out of work and who are going to need cash assistance to meet their basic needs and SNAP to meet their food needs.”

Into the winter

Predicting where welfare usage will head in New York City over the next year or more is difficult. The timing of a vaccine’s arrival, the trajectory of federal relief, how soon tourists return and office workers come back (if ever)—all are uncertain. Banks is hopeful the Biden administration will come through with aid that helps the most vulnerable. Levin is uncertain of the prospects for efforts to shore up other parts of the city’s safety net, like rental vouchers, given the poor fiscal outlook.

As time goes by, if public-health measures are successful, New Yorkers will talk less about COVID-19 and more about the economic shockwaves. For many of the families applying for welfare, Newton notes, the two crises are one in the same.

“We’ve had so many people who’ve had somebody die in their household from COVID. That’s always very painful,” he says. One of his jobs is to help clients with applications for burial assistance from the welfare system. “I had maybe done two of those in 20 years. And now I’ve done more than we can count.”