For tenants in the first upstate city to adopt rent stabilization, benefiting from the law’s basic protections is an uphill battle.

Adi Talwar

Kingston tenant Sarah Cizmazia in her Chestnut Mansion apartment in June.Editor’s Note: This story was produced in collaboration with New York Focus.

Sarah Cizmazia is quick to explain that the name of her apartment complex in Kingston, New York—Chestnut Mansion—is “very grandiose for what it is.”

When she arrived at the brick, garden-style building in April 2023, one of the first things she noticed was the bent door to her apartment. Gaps around the frame let in bugs and cold drafts.

This wasn’t the only surprise. Coming from Connecticut, she had no idea that her landlord was under state regulation. The prior July, Kingston had become the first locality outside New York City and its surrounding counties to adopt rent stabilization.

But it wasn’t the property manager, Opus Management Group, that told her so. Instead, she learned about the new law from a flyer. A local progressive group, For the Many, was looking to start a tenants union at Chestnut Mansion, and Cizmazia had been invited to the first meeting.

In New York City, the broad strokes of rent stabilization are well known. Tenants lucky enough to live in one of the city’s roughly 1 million regulated apartments enjoy below-market rents and the right to renew their leases. Each year, landlords can only increase rents as much as a government-appointed board allows.

Thanks to reforms the state passed in 2019, any city or town with a sufficiently low vacancy rate can now adopt the regime, which is governed by New York’s 1974 Emergency Tenant Protection Act, or ETPA. Poughkeepsie did so recently, and Albany is on its way.

But as renters in Kingston are learning two years in, adopting the law is only the beginning. Their first regulated leases were supposed to include an unprecedented 15 percent reduction, but after landlords sued, tenants have yet to see their rents go down.

Many landlords have not kept up with registering their apartments, as the law requires. And while there are mechanisms for fighting overcharges and demanding repairs, tenants aren’t necessarily familiar with them, much less comfortable standing up to their landlords. Those brave enough to do so are navigating complex bureaucratic channels.

Cizmazia’s warped door and the exterior of Chestnut Mansion in June. (Adi Talwar for City Limits)

“When I rented before, in other places, you’re basically taught, ‘Keep your head down,’” Cizmazia explained recently. But in late November, after living for months with the bent door, she submitted a complaint to the state agency that administers the rent laws, the Division of Housing and Community Renewal. A DHCR inspector confirmed in January that the door was “warped” and directed her landlord to fix it.

They didn’t. In May, Cizmazia submitted another form. She’s waiting to hear about next steps, which could include a hearing and eventual fine. “I feel safer that I can’t just get evicted at the drop of a hat like I could have when I lived in Connecticut, right?” she said. But it’s still stressful. “I wish that there was better enforcement.”

Battling rising rents

In the spring of 2022, the City of Kingston sent surveys to 64 properties that appeared to qualify for rent stabilization based on their size and age—those with at least six units, built before 1974. The vacancy rate across roughly 1,200 apartments was 1.57 percent, below the state’s 5 percent regulation threshold. Kingston’s Common Council declared the housing emergency effective that August.

The local economy looks very different today than it did in the mid-1990s, when IBM closed its plant in Kingston, about 100 miles north of New York City. “We weren’t able to rent half our apartments,” recalled local landlord Joel Kaminsky, who owns an eight-unit Victorian covered by rent regulation.

Kingston is now a popular scenic escape from New York City. Ulster County, where it’s located, saw the median rent for a two-bedroom jump 25 percent between 2018 and 2022, to $1,500. A Kingstonian earning the average local wage among renters would need more than two full-time jobs to afford a typical two-bedroom.

The rapid rise in housing costs was top of mind for the city’s inaugural Rent Guidelines Board in the fall of 2022. Under the ETPA, each local government selects nine people to vote annually on reasonable rent adjustments based on the economic conditions that both landlords and tenants are facing. (DHCR gets final approval of each appointee.)

Landlords testified before the board about the high cost of fuel and maintenance, but were outnumbered by tenants describing unaffordable rent. “People came and poured their hearts out,” said Carol Soto, one of the board’s tenant representatives. “It was incredible.” The final vote was 6-3 for a 15 percent cut—the first reduction by a rent board in ETPA history.

But it was short-lived. A local landlord group, the Hudson Valley Property Owners Association, was already suing to block implementation of the ETPA. The group alleged that Kingston’s vacancy survey was flawed. And while a county judge found the survey sound, he deemed the rent cut an overstep.

A higher court eventually revived the rent reduction this March, saying that the law doesn’t require adjusting rent “upward rather than downward.” But another appeal is already underway. For the Many has advised tenants not to demand reductions just yet, for fear that landlords will prevail in their suit and seek repayment of the difference.

The Hudson Valley Property Owners Association’s legal efforts extend beyond Kingston. It was recently successful in stopping rent regulation 40 miles to the south in Newburgh, where a judge ruled that the vacancy rate calculation “lacked a rational basis.” Its next target is Poughkeepsie, which opted into rent stabilization in June with the largest coverage to date in the region: about 1,500 apartments. (That number is likely to be eclipsed by Albany, where a vacancy survey is underway.)

“We don’t really believe there is this, quote, ‘housing emergency,’” Rich Lanzarone, the association’s executive director, said during a phone call this spring. “The idea that a 5 percent vacancy rate represents an emergency is ridiculous. That’s actually a healthy market.”

Landlords lax on building registration

Despite the litigation, landlords across Kingston’s rent-stabilized buildings are expected to operate within a basic legal framework. Rents are supposed to be frozen at August 2022 levels, and any service in place at that time, from a working doorbell to a parking space, must be maintained. Evictions without a specific reason, like failure to pay rent, are unlawful.

Owners are also obligated to register annually with the state and mail a copy of the record, including the legal rent, to each tenant. Where rent regulations are still fresh, registration can serve as notice to tenants that they’re protected. Over time, it can also help them identify suspicious rent increases.

Registration is especially important because the rent stabilization system is largely complaint-driven, meaning tenants need the knowledge, time, and wherewithal to enforce their rights, often by submitting complicated paperwork to DHCR.

But DHCR reported in June that just eight of over 60 eligible properties in Kingston had completed their 2024 registrations, ahead of a July 31 deadline. That’s not including 12 properties whose owners have requested or received state exemption from the law (in some cases, to compensate for costly past renovations). Ten landlords still hadn’t completed an initial registration that was due by Halloween 2022.

DHCR hasn’t adequately educated property owners of their responsibilities, according to Anthony “Junior” Tampone, a landlord representative on Kingston’s Rent Guidelines Board. “They should be doing what they need to in order to encourage participation,” he said.

Kaminsky, the small landlord with the eight-unit Victorian, said the registration process was “super confusing,” taking several hours and multiple phone calls to DHCR.

The Hudson Valley Property Owners Association, the same group suing to block the ETPA, is encouraging its members to follow the rules, according to its co-leader Jim Lamb, CFO of the Kingston real estate management firm Sanzi Associates.

“We are very much adamant about telling people to do all of these things and do them on time,” he said. Lamb believes housing providers—he prefers the term to landlords—are unfairly villainized. But the association can only do so much. “You can lead a horse to water, but you can’t make them drink,” he said.

Local enforcement needed

Woody Pascal, deputy commissioner of DHCR’s Office of Rent Administration, had firm words for Kingston landlords at a June Rent Guidelines Board meeting. His office is the agency’s administrative arm, responding to tenant complaints and meting out fines and rent reductions. “You can’t skirt the law and think that it’s going to be okay,” he said.

Starting in August, Pascal explained, owners who are late in registering will face steep fines of $500 per apartment per month. The new rule is part of a 2023 law that shored up various aspects of rent regulation. Landlords won’t be able to appeal administratively, like they can with other DHCR orders.

He also blamed litigation for his office’s “starts and stops” in Kingston. Once that’s cleared up, he said, there will be informational nights for owners and tenants and perhaps office hours at City Hall. “We’re going to do what we need to do,” he said. “Spending more time in beautiful downtown Kingston is not a problem.”

Adi Talwar

Downtown Kingston in June.But tenant advocates say more needs to be done. Rather than relying heavily on renters to initiate complaints within an unfamiliar regulatory regime, they say, DHCR should open a Hudson Valley outpost for its Tenant Protection Unit.

Launched in 2012 and headquartered in Manhattan, the TPU is DHCR’s self-described “proactive law enforcement office,” tasked with rooting out patterns of landlord misconduct, like illegal rent increases, registration lapses, and systemic harassment.

Pascal’s team can fine landlords and pull them into hearings, but the TPU has a bigger hammer. Crucially, it has subpoena power, meaning it can force owners to provide sworn testimony and business records. But the unit is small: 24 full-time staff, eight of whom are lawyers. The Office of Rent Administration, by contrast, is over 300 strong.

The state budget finalized in spring 2022 included $600,000 in new funding to create a TPU outpost in the mid-Hudson Valley in 2024, but the office has yet to materialize.

“I think people here would get in their cars and go to a TPU office,” said Soto, the Kingston Rent Guidelines Board member, who is a rent-stabilized tenant herself. “If they felt like they had no recourse, then they could take [their] questions to the TPU, and yes they would be bombarded, but maybe it would get [DHCR] off its butt.”

DHCR did not respond to questions about when the office will open, stressing instead that it is actively recruiting for the unit. But in June, the head of the TPU, Deputy Commissioner Pavita Krishnaswamy, discussed the expansion plan in some detail with a group of Kingston tenants.

“We have two problems—one is space, and one is hiring,” Krishnaswamy said, according to a recording of the meeting reviewed by City Limits and New York Focus. In the meantime, she urged tenants to contact her office by phone or email.

“The vision is that it would not just be lawyers but it would be paralegal advocates who can answer the phone, come out to buildings, see conditions with their own eyes, meet with tenants,” she added. “It’s one of the things I have learned, working in government, it takes time. But we’re persisting.”

State Assemblymember Sarahana Shrestha, who represents Ulster County, said she would like to help sort out the office space issue. In general, she said, the state needs “a more serious commitment to empowering DHCR to do enforcement.”

A vocal tenant advocate, she said her recent re-election is proof that renters outside New York City are starting to feel like a political bloc: “Here, everything is hinging on this new learned habit of being active tenants fighting for something.”

Adi Talwar

Tenants rally for rent stabilization at a Poughkeepsie Common Council meeting in April.“They’re out for money”

For now, whether the basic protections of rent stabilization are felt in Kingston varies across complexes, and sometimes from one tenant to the next.

Lamb, of Sanzi Associates, said rents have remained flat at the 21 apartments in his two rent-stabilized properties. (“I mean, you’re required to by law.”) Same with Kaminsky’s building, though he’s not happy about it. “Our rents are below market value, so it’s very frustrating,” he said.

By contrast, tenants at Stony Run—Kingston’s largest stabilized complex, with over 200 garden-style apartments—started organizing in 2022 under threat of rent hikes from their new landlord, Aker Companies. The investor’s stated specialty is properties at the “intersection of urban and outdoor environments.”

Stony Run tenant Teresa Greene, now an elected liaison between her neighbors and Aker, received a lease renewal in September 2022, after rent regulations took effect, that included a new $65 amenity fee and $187 rent hike. She refused to sign it, and helped convince many of her neighbors not to either. (Aker Companies did not reply to questions about why it sought to increase rents after the rent laws took effect.)

Around that time, the City of Kingston sent eye-catching pink and yellow mailers to newly regulated tenants, telling them that they were now covered by the ETPA. For the Many and another grassroots group, Citizen Action of New York, jumped in to help explain what that meant.

But organizing didn’t get off the ground as quickly at Chestnut Mansion. With 59 units, it, too, is on the larger side for local ETPA properties. In May 2023, tenant Kristine Glass signed a renewal lease that included a $50 rent increase. “We weren’t aware of the regulation at that point,” she explained. Then she started noticing rodent droppings—she guessed mice, but it turned out to be rats.

In October, Glass contacted For the Many tenant organizer Jenna Goldstein, who explained the rent increase never should have happened. Glass’s partner called the building manager to say the hike was illegal, given the rent freeze. By December, it had been withdrawn and they were refunded the difference.

“It opened up a new reality for us,” Glass said. “Because we realized that the people who own our building aren’t out for our best interest, they’re out for money.”

Tenants can also submit a form, called an RA-89, to challenge their initial base rents or any increases since the city opted into stabilization. It calls for tenants to provide up to six years of leases and proof of rent payments. As of June, DHCR said it had not received any complaints from tenants in Kingston regarding rent hikes, though it had received 52 forms challenging base rents.

Goldstein, who is currently working on an overcharge complaint for a local renter, believes the entire process must be simplified for people to reasonably take advantage of it.

“DHCR has to make it comprehensible and digestible for everyday people,” she said. She estimates that she spends 20 hours each week helping tenants navigate the new rent laws, explaining the basics and trying to help them overcome fears of retaliation. “If they don’t know their rights, they can’t possibly advocate for them.”

Adi Talwar

For the Many tenant organizer Jenna Goldstein outside her office in Kingston in June.If and when overcharge complaints start rolling in, DHCR is not known for quick processing. A state comptroller audit found that complaints submitted between 2010 and 2012 took more than a year and a half to resolve on average.

Service reduction complaints—like Cizmazia’s door—were addressed somewhat faster.

Typically, in these cases, landlords have to stop collecting their most recent Rent Guidelines Board increase until the problem is fixed. But that leverage doesn’t currently exist in Kingston, where the last adjustment on the books was a rent cut.

In a statement to City Limits and New York Focus, DHCR spokesperson Charni Sochet said the Office of Rent Administration “administers the rent laws as enacted by the legislature” and ensures they are enforced through “proactive audits, investigations, and other enforcement activities.”

Online filing and simplified paperwork have helped speed complaints along in recent years, according to the agency, and the new state budget includes funding for 35 additional rent administration staffers. But due process takes time, it noted.

In certain situations, time is of the essence. In February, for example, a carbon monoxide leak forced tenants at three Chestnut Mansion buildings to evacuate for a week. (Opus did not reply to questions about building conditions or its responsibilities under regulation.) Goldstein emailed the TPU saying she planned to submit complaints but needed more support.

The office replied within a few hours with an email, linking to various forms. The TPU is based in Manhattan, it said, and “does not have the resources to address service related issues in Kingston.” Instead, DHCR will respond to problems “via the complaint forms that were referenced.”

This was all too much for Molly Rogerson, who lived in one of the evacuated buildings. By April, she and her partner had moved out, to a more expensive apartment in town. “I felt like my hands were tied,” she said.

Looking ahead

As housing groups work to spread the ETPA across the state, challenges in Kingston have put tenant education front and center. In February, United Tenants of Albany held a teach-in at the local library with Marcie Kobak, of Legal Services of the Hudson Valley, and Michael McKee, a veteran organizer in New York City.

“This is not ‘How to run a campaign to get ETPA enacted,’” McKee told the crowd. Instead, he led off with a pop quiz about what the law regulates: tenants’ rents, their ability to remain in their apartment from one year to the next, and the services landlords must provide.

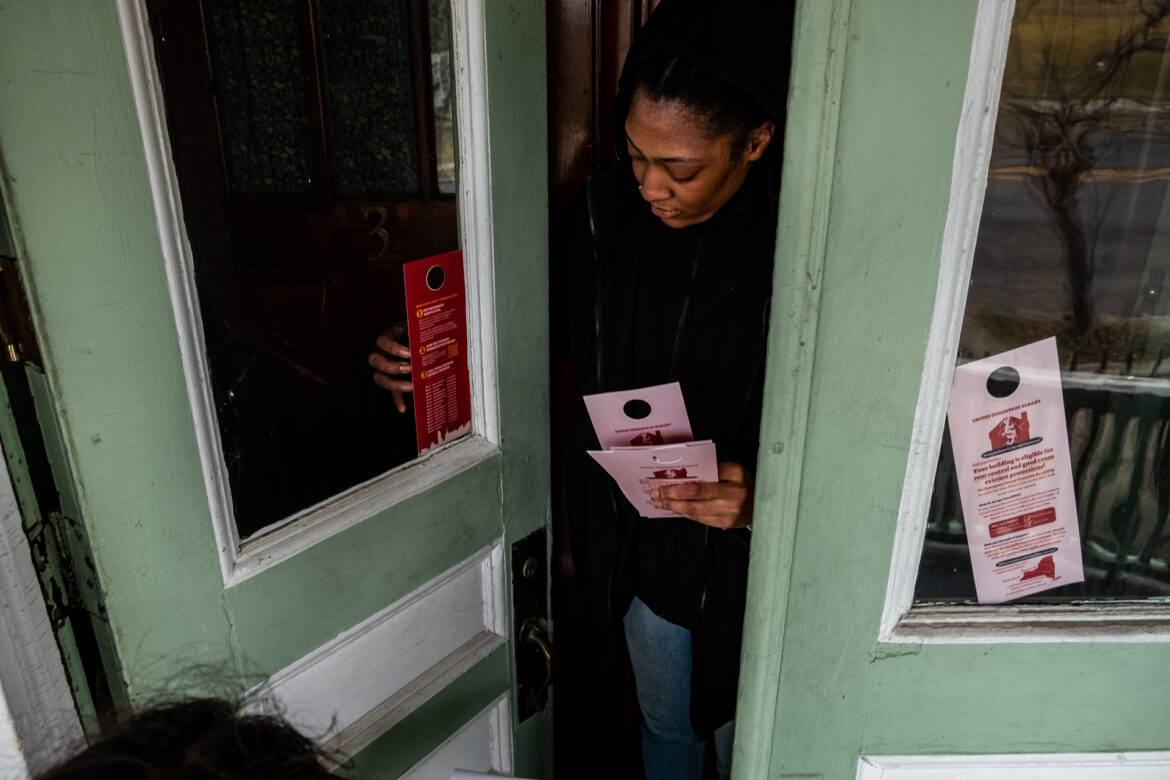

About a month later, United Tenants of Albany hosted a door-knocking session to get the word out and collect phone numbers and emails.

Mehr Sharma, an organizer with United Tenants of Albany, leads a training ahead of ETPA door-knocking in March. On the right, tenants leave flyers at potentially-eligible apartment buildings. (Adi Talwar/City Limits)

A vacancy survey is still underway in Albany, but organizers there see potential for a sea change. More than 40 percent of the renters they helped last year didn’t even have a lease. Under the ETPA, not only are landlords obligated to provide them, but tenants would have a chance to negotiate the initial terms.

Canyon Ryan, United Tenants of Albany’s executive director, is also excited about the prospect of Rent Guidelines Board meetings, where tenants could testify and, hopefully, feel a new sense of power in numbers. “It politicizes the issue of rent,” they said.

In June, Cizmazia took the podium at a Kingston Rent Guidelines Board meeting to testify in favor of a rent freeze for the coming year, which she said was “beyond fair for the working class who are struggling to find jobs to pay their bills.”

She had been laid off from her tech job but was confident that she would not face retaliation for testifying. This feeling didn’t come easily, Cizmazia explained recently: “It took basically the whole year I’ve been living here to slowly become more comfortable with speaking out.”

McKee, from New York City, has felt this empowerment for decades. He has lived in the same apartment in Chelsea since 1974, despite his landlord’s best efforts to evict him while his late partner was battling AIDS. Regulation—in his case, rent control, which provides similar rights to its sibling, rent stabilization—has “given me stability that otherwise I wouldn’t have,” he said.

Adi Talwar

Michael McKee in his home office in Chelsea in May. His late partner, the artist Louis Fulgoni, is in the framed photo behind him.Next year, the statewide coalition Housing Justice for All, of which he is a part, hopes to introduce legislation which would expand ETPA eligibility to the smaller and newer rental buildings that are common outside New York City.

And a longtime dream is starting to feel more attainable to him: instigating a major operational shift at DHCR. He pictures more proactive investigations and less complaint-driven bureaucracy. The last two years of “chaos and confusion” in Kingston have helped clarify this demand.

“This is a law,” he said. “This is not optional.”

To reach the editor, contact Jeanmarie@citylimits.org

Want to republish this story? Find City Limits’ reprint policy here.