While lawmakers continue to negotiate development incentives and tenant protections in Albany, supporters of the Faith-Based Affordable Housing Act are positioning the bill as one of the state’s best shots at passing meaningful housing legislation this year. “It’s hard to put your guard up when it’s the neighborhood church saying we want to build,” sponsor Andrew Gounardes told City Limits.

State Sen. Andrew Gounardes’ Office

State Sen. Andrew Gounardes and supporters of the Faith-Based Affordable Housing Act at a rally in Albany on March 5, 2024.While Albany lawmakers continue to debate development incentives and tenant protections in Albany, supporters of the Faith-Based Affordable Housing Act are positioning the bill as one of the state’s best shots at passing meaningful housing legislation this year.

Proposed in December by State Sen. Andrew Gounardes, the legislation would make it easier for religious organizations to build affordable housing on their properties, essentially becoming landlords.

And while not as far-reaching as other housing-related proposals being haggled in Albany—and a year after Gov. Kathy Hochul’s mandated development proposal fizzled out—supporters of the FBAHA hope it will prove a less divisive option to spur new homes across the state.

“I think a lot of people were skittish about the notion of trying to do everything in one big grand slam swing,” Gounardes told City Limits. “So we’ve taken a bit of a different approach. We think that starting with faith based institutions, which are obviously trusted partners and communities, trusted institutions, and allowing them to make it easier to do what they want to do, which is to help create housing for people, was a much lower barrier to entry.”

The concept is not unfamiliar to Gounardes: in fact, a similar faith-based housing initiative was a priority during Mayor Eric Adams’ tenure as Brooklyn borough president, a time when Gounardes served as his counsel.

Largely modeled on the successes of California’s Affordable Housing on Faith Lands Act, which eased the zoning red tape for faith-based organizations and nonprofit universities (excluded from New York’s version), the bill would help create substantial affordable housing on what is typically untaxed land.

If passed, it would allow religious institutions like temples, churches, mosques, and synagogues “to bypass local zoning laws that restrict their ability to develop their land,” as long as that new development includes affordable housing. In areas with fewer than 1 million inhabitants, 20 percent of constructed or converted residences under the law must be allocated for households earning 80 percent of the Area Median Income (AMI).

In cities with 1 million or more residents like New York, residential buildings must adhere to one of three options: allocate 25 percent of floor area for households earning 60 percent of the AMI—equivalent to $84,720 for a four-person household—with at least 5 percent of units affordable to those at 40 percent of the AMI. Alternative options would require 30 percent of floor area for households earning 80 percent of the AMI, or 20 percent of floor area for households earning 40 percent of AMI, the bill states.

State Assemblymember Brian Cunningham, who is sponsoring the legislation in the Assembly, pointed to rising rents in his Central Brooklyn district as evidence that “we desperately need to create a new dynamic in the housing market.”

“Once a haven for middle-class families, Flatbush and Crown Heights now see one-bedroom apartments priced at $3,000 a month,” the lawmaker said in a statement to City Limits. “The FBAHA offers a sustainable, long-term solution by leveraging the trust and reach of our religious institutions to build the vital housing our community needs.”*

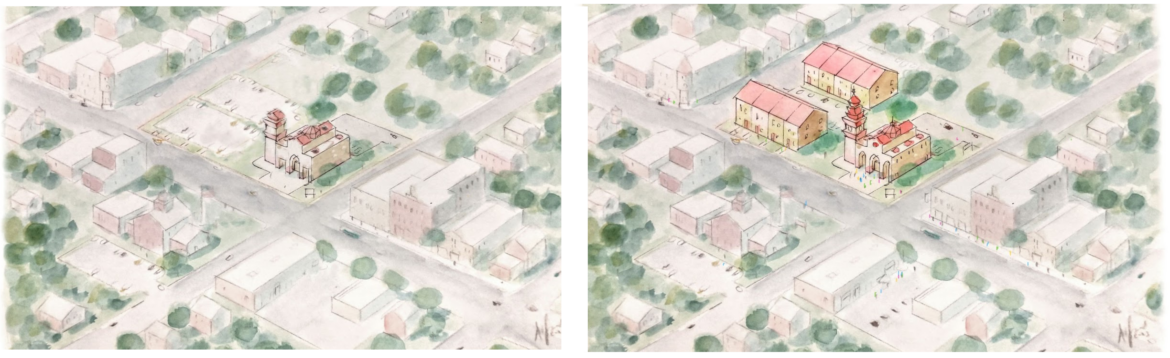

Open New York

A before-and-after rendering of how a religious organization could use the proposed law to develop its property.So far, the legislation has 18 co-sponsors in the Assembly and 11 in the State Senate, including progressive democrats such as State Sen. Julia Salazar and Assemblymember Emily Gallagher. It’s also earned the support of Queens State Sen. Leroy Comrie, who last year was among those opposed to Gov. Hochul’s housing plan and was a vocal critic of efforts to legalize basement apartments. Both the Senate and Assembly housing chairs, State Sen. Brian Kavanagh and Assemblymember Linda Rosenthal, have signed on as well.

“We’ve just been constantly talking to folks little by little, and building up quiet support, because it’s hard to object if a church says, ‘Hey, we have a parking lot, or we have an unused rectory or an unused school building or some other type of asset that we have no use for anymore. We want to turn it into housing,’” said Gounardes. “It’s hard to put your guard up when it’s the neighborhood church saying we want to build affordable housing.”

According to a recent Pew Research report, 75 percent of New Yorkers support a form of faith-based housing. Reverend Dustin Longmire is one of them.

His congregation, Messiah Lutheran Church near Schenectady, acquired and merged with a neighboring church with lagging membership in late 2021. His congregation began speaking with experts on how to best put the acquisition to good use.

The property is located in a unique zoning overlay district, and the final recommendation was to convert it into a community center as well as affordable housing.

“In my mind, we could use this development opportunity to serve us,” said Longmire. “In a town that doesn’t really have a main street it’d become a kind of a central hub in a lot of ways, and really do some strong place-making, knitting the fabric of community together while also providing housing for some of our neighbors.”

The community center component opened in June 2022, and the church still hopes to develop affordable housing at the site. “We have a pretty conservative town board but really good people who might not be super oriented towards affordable housing, but they’re talking with us,” Longmire said.

According to data provided by NYU Furman Center, 4.6 billion square feet of potential housing could be unlocked across the state via FBAHA’s passage, significantly more than the 76 million square feet that could be provided by converting unused office space, the bill’s supporters wrote in a Daily News oped in December.

Under the legislation, any congregation that enters into a development agreement will have to undergo a mandated training on housing, “so that they can enter into working with a developer in a responsible way so that they don’t get exploited,” said Rev. Peter Cook, executive director of the New York State Council of Churches, who helped write the bill alongside pro-development organization Open New York.

“In terms of faith organizations wanting to do this work, this is really common,” said Andrew Fine, Open New York’s policy director.

“It just really takes too long. A lot of projects take five, 10, 15 years just to cut through the financing and environmental review and rezoning processes and given the [housing] crisis, we just don’t have that time,” Fine said. “So really, this is taking a lot of projects that people love the outcome of, but that get mired in endless processes and trying to shorten it.”

For Longmire, he believes the bill would help faith-based organizations accomplish what most of them aim to do in their communities: act as forces for public good.

“Supporting this bill will just free up faith communities more to provide the same sort of services that we historically always have,” he said. “The church was always a part of figuring out infrastructure and housing and health care and all these sorts of things, and this is just a 21st century version of that.”

*This story has been updated since original publication to include additional comment from Assemblymember Brian Cunningham.

To reach the reporter behind this story, contact Chris@citylimits.org. To reach the editor, contact Jeanmarie@citylimits.org.

Want to republish this story? Find City Limits’ reprint policy here.

2 thoughts on “Amen to New Housing? Faith-Based Development Bill Looks to Secure Legislative Blessing”

The devil (sorry for the pun) is in the details. Does the religious institution have to remain 100% owner? 51%? less? Both building and land? Just land? Permit tax credit investors to own 99%. Are all provisions of the zoning resolution waived? Window to wall requirements? Height? Parking? Yard? Stair egress?

Is this constitutional? Favoring religious organizations?

Many developments involving religious institutions have been done without any noticeable greater acceptance by the surrounding communities. There have also been problems with many of these.

Be wary of what you wish for. It’s no fun being a landlord and this will be especially true for religious institutions. Q: Are they going to evict tenants who don’t pay their rent?

The problem with the holier than thou sounding word “faith” is what the organization has “faith in.”