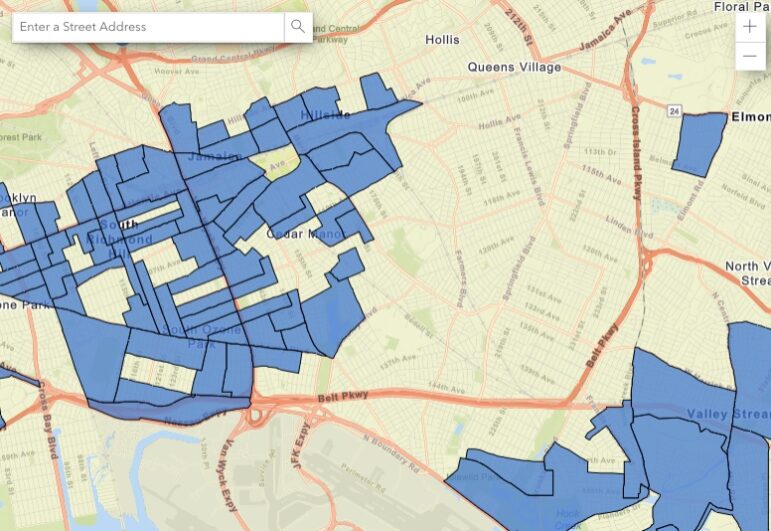

Under New York’s climate law, “disadvantaged communities” that have borne the brunt of pollution and other environmental issues are being prioritized for funding and climate-related benefits. But swaths of Southeast Queens didn’t make the cut, what local leaders say was an oversight.

Adi Talwar

A low-flying commercial aircraft passing over Southeast Queens near John F. Kennedy International Airport. Proximity to an airport wasn’t one of the factors the state considered when drafting its Disadvantaged Communities designations.Southeast Queens has seen its fair share of environmental concerns, including the effects of hurricanes as well as decades of flooding and sewer backups. That’s why many residents and stakeholders were disappointed this past spring, when the state designated more than 1,700 census tracts as “disadvantaged”—but left many parts of Southeast Queens off the map.

Carrying this “disadvantaged communities” (DAC) label is crucial: it means those neighborhoods will be first in line for money under the state’s green transition by the year 2050, as well as for projects aimed at relieving environmental, climate and health inequities.

Last week, for example, Gov. Kathy Hochul announced $20 million to help finance “clean energy and sustainable infrastructure projects” that specifically benefit neighborhoods with the DAC designation. And on Thursday, as part of a Climate Week announcement alongside governors from Washington and Maine, Hochul committed to vastly expanding the number of heat pumps installed across the state, “with the aim of ensuring at least 40 percent of benefits flow to disadvantaged communities.”

“It doesn’t make sense,” said State Senator Leroy Comrie about areas in his district that were left off the map, including census tracts in Hollis, St. Albans and Addisleigh Park.

Shortly after the final map was released this spring, advocates from the Eastern Queens Alliance, Inc., a consortium of neighborhood organizations and community groups, wrote a letter to state lawmakers saying they should review the maps and asking why other, wealthier parts of the state are labeled as “disadvantaged” while theirs are not.

“…some gentrified/more affluent, majority white communities like Hudson Yards, Williamsburg, Greenpoint, and the Hamptons are designated as disadvantaged and are therefore eligible for this special funding,” reads the letter.

The criteria for a tract being “disadvantaged” was based on 45 data points, including income, race and ethnicity and health impacts, such as low birthweight. Other factors included the cost burden of energy bills and how many older people live in an area.

The state’s Climate Justice Working Group, which worked with a state panel to come up with the criteria, consisted of representatives from state agencies as well as nine environmental justice advocates from across the state. Three of those nine advocates were from New York City, though none were from Queens, what those critical of the maps say was a blind spot.

Advocates, as well as elected officials who represent the area, were also disappointed that proximity to an airport was not one of the data points considered when determining whether a community is considered disadvantaged, overlooking the noise, traffic and air pollution impacts that John F. Kennedy airport has had on surrounding communities.

“It is critical that the Disadvantaged Community Map fully reflects these realities,” said Senator James Sanders Jr., whose district includes parts of South Ozone Park, Springfield Gardens and Brookville.

Screenshot/NYSERDA

A screenshot of the state’s “Disadvantaged Communities” maps, with DACs shaded in blue. Many census tracts in Southeast Queens didn’t get the designation, despite a history of environmental and infrastructure issues highlighted by locals.DEC did not provide an answer to City Limits as to why airport proximity was not considered, but said the Climate Justice Working Group looked at more than 170 potential indicators and ultimately decided on the final 45.

“The DAC criteria process included a robust public comment process that included a 150-day public comment period, 13 public hearings, two public education sessions and generated over 3,000 comments,” the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) said in a statement.

The Climate Justice Working Group will review and update the DAC designations annually, and “will examine available data to determine if the disadvantaged communities’ criteria and list census tracts require modifications,” according to the state.

Comrie, Sanders and Assemblywoman Alicia Hyndman, whose district includes parts of Jamaica and Addisleigh Park, said they’re committed to working with advocates and constituents to ensure more sections of Southeast Queens are included in future updates.

“Moving forward, I hope there will be continued adjustments where needed,” Hyndman said.

Many environmental and climate issues in this part of Queens disproportionately affect people of color. More than 40 percent of residents in Queens Community Boards 12 and 13 are immigrants. Both districts are majority Black, including neighborhoods such as Springfield Gardens, Queens Village and St. Albans. Some of these communities sit next to highways, bus depots and JFK airport.

City Limits spoke to neighbors in this corner of Queens about how the effects of climate and environmental matters play out in their communities.

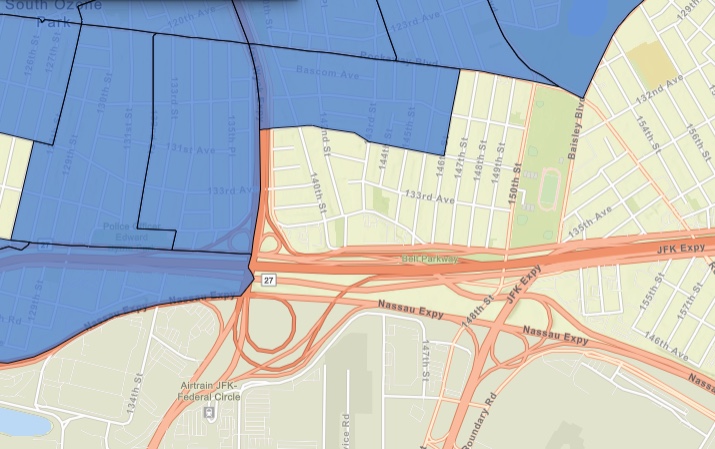

Springfield Gardens and South Ozone Park

Adi Talwar

Traffic at the intersection of Rockaway Boulevard and North Conduit Avenue. While vehicle traffic density is one of the data points considered under the state’s “disadvantaged” criteria, this census tract didn’t make the final list of priority neighborhoods.It was important for Aracelia Cook to walk to Burger King on the corner of Rockaway Boulevard and North Conduit Avenue—known to locals as “The Conduit”—to get her steps in. On that corner, there’s also a 7-Eleven, Punjab Liquor & Wine and a Tandoori chicken spot. But the Burger King is extra special to her: She knows the manager, and it’s where one of her five children got his first job before he passed away.

The Springfield Gardens Burger King is below the Belt Parkway, where cars whisk by to get to JFK Airport, to Brooklyn or to the nearby Van Wyck Expressway. Even though vehicle traffic density is one of the data points considered under the state’s “disadvantaged” criteria, this census tract didn’t make the final list of priority neighborhoods.

Cook’s home is about a 20-minute walk away in South Ozone Park, where she’s lived for most of her 65 years. She’s seen the area change, from mostly white residents to more Black neighbors moving in in the 1970s, and now a growing Asian population from places such as Pakistan and Bangladesh.

Adi Talwar

Adi Talwar

Adi Talwar

Screenshot/NYSERDA

Above: Aracelia Cook in front of her home on Inwood Street. While her census tract was given the “disadvantaged communities” designation, other nearby areas—including homes along 133rd Avenue (top right corner)—did not. The shaded blue areas in the map in the lower right hand corner indicate DAC-designated tracts in South Ozone Park. Photos by Adi Talwar.

She and the nearly 800 other households in her census tract are considered “disadvantaged” by the state. But if she walks about a block east or south, she finds it baffling that her neighbors are not. She recalled a gargantuan sewer backup in the area in November 2019, when a broken 42-inch pipe caused raw sewage to flood hundreds homes in an area bound by Baisley Pond Park, the Van Wyck Expressway, and Rockaway Boulevard and the Belt Parkway.

After initially blaming residents for clogging the city’s pipes with grease over Thanksgiving weekend, the city took responsibility for the incident, which one researcher told the New York Times amounted to “a problem of environmental racism.”According to the NYC Department of Environmental Protection, sewers have a lifespan of about 100 years; the collapsed sewer was built in the 1980s by the state.

“This failure should never have happened,” said a DEP spokesperson. The agency constructed a new sewer around the collapsed one in 2020.

“I’ll never forget that day,” Cook said. “There are still families who are not back in their basements.”

Addisleigh Park

Adi Talwar

Homes on 178th Street in the Addisleigh Park neighborhood.A stroll through leafy Addisleigh Park will lead you past hundreds of Tudor homes. The area, a section of St. Albans, is known as the former home of musicians, artists and baseball players, including Lena Horne, Jackie Robinson, Count Basie and countless others. In 2011, the neighborhood earned landmark status and became a historic district.

Valerie Jordan Garvin moved to Addisleigh Park in the early 1960s when she was just in the third grade. By the time she attended P.S. 36, she remembers her classmates being mostly Black. “Everyone looked out for each other’s children,” she says. “It was close-knit.”

There are not many of those people left on the block now, she says. Many have died. Jordan Garvin is in her mid-60’s, and moved out of her childhood home when she was in her 20s. She lives not far, in South Jamaica, and comes back to help her 85-year-old mother, who still lives in Addisleigh Park.

In her mother’s dining room, quiet rumbles can be heard from two pumps installed in her basement to keep water out. She says her family has dealt with flooding in the home for almost 30 years.

That’s because the Jamaica Water Supply Company used to pump groundwater out of the area. But she says since the NYC Department of Environmental Protection took over the wells of the company in the 1990s and ceased pumping from them, intense flooding began in her home.

DEP is in the midst of a $2.65 billion plan to build a comprehensive drainage system and address flooding in Southeast Queens. “This is the largest such investment anywhere in the city,” said a spokesperson to City Limits.

Adi Talwar

The basement of Valerie Jordan Garvin’s mother’s home, where a pump system is triggered by the water level and runs every few minutes to prevent flooding. Photos by Adi Talwar.

According to the agency, flooding issues nearby are exacerbated by streams running under houses in the neighborhood, which could cause fooding. DEP says it has made efforts to monitor groundwater flooding—which can be worsened by rising sea levels and increased rainfall due to climate change—and redirect water away from homes.

Still, most of Addisleigh Park was not labeled “disadvantaged” by the state. Because of the barrage of water, Garvin’s mother pays to keep the pumps running. That means an electricity bill of about $225 per month on a limited income.

“It’s not like she can shut them off,” Garvin said.

Once a year, she says she pays $150 for the pumps to be replaced because they wear out from so much use. “I think the water issue is the main issue,” she says about her neighborhood. “We’d like to see that solved.”

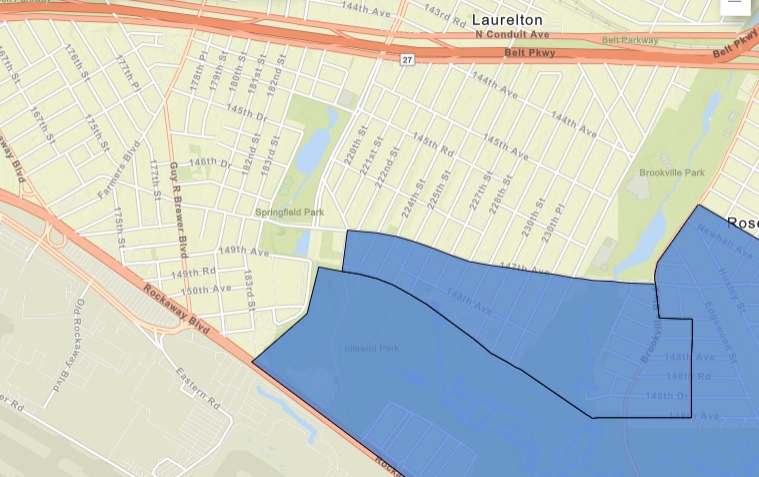

Screenshot/NYSERDA

A screenshot of Springfield Gardens and Brookville on the state’s map of “disadvantaged communities” indicated in blue.

Brookville and Springfield Gardens

The bumpy two-and-a-half-miles of 147th Avenue is lined with mostly residential houses. The busy thoroughfare is frequented by pedestrians, drivers, cyclists and bus passengers on the Q111, who pass by a laundromat, deli, a church or two, and warehouses related to cargo at JFK airport.

On the western most part of the road is Springfield Gardens. A tractor trailer houses large trucks, as men direct more trucks going in and out of a warehouse there. Exhaust diffuses into the air.

But for residents like Cassandra Bell, 71, the heavy traffic comes with the territory of living adjacent to a busy international airport. “It doesn’t bother me,” Bell says. Some of her neighbors on her block shared her sentiment. Bell has been in her home for about 40 years, which she was able to buy through a federal housing program.

Trucks and warehouses interspersed between residential homes in Springfield Gardens, Queens. Photos by Adi Talwar.

The exhaust used to be worse, she remembers, when there was a gas station nearby and trucks would be parked for long periods of time.

Further east in Brookville, off the side streets of 147th Avenue, two adjacent gray warehouses—home to freight, shipping and logistics businesses—take up nearly a city block each.

Mordie Hicks has rented an apartment in a two-family home on 227th Street since 2019. “It’s horrible,” said Hicks of living near the busy truck hubs.

“All they [the truck drivers] do is rush down the street all day,” he says. “They don’t watch out for pedestrians, they don’t watch out for cars.”

Hicks is wheelchair-bound and relies on an ambulette to get around town. “I’m handicapped. I get dropped off by the ambulette. They honking at the ambulette,” he said, shaking his head. Sometimes he hears trucks rumbling by at two in the morning.

Adi Talwar

Mordie Hicks has rented an apartment in a two-family home on 227th street since 2019. “It’s horrible,” said Hicks of living near busy airport truck hubs.His partner, Hazel Griffith, says because of the narrow streets, sometimes neighbors have to leave their homes to help direct trucks. Griffith is also tired of being so close to the airport.

“They seem like they’re literally just right at the edge of the top of the house,” says Griffith about the planes. “Yeah, I can feel the vibration and I can hear the big engines.”

The couple hasn’t been following what’s been happening with the state’s disadvantaged communities designations. But they were both shocked to learn their home wasn’t included among the prioritized census tracts.

“Are you kidding me?” asked Griffith.