A real estate trust bought single-family homes in gentrifying Brooklyn neighborhoods, renovated, and rented them out at a premium. With the trust now looking to offload the assets, tenants are left in an uncertain position, feeling like homeownership is further out of reach than ever.

Adi Talwar

Homes along MacDonough Street in Brooklyn.When the Barnes family decided to move back to Brooklyn in 2021, they were looking to buy a home. Like many families, they had to delay that dream in New York’s scorching housing market, fast rebounding from a pandemic dip.

Instead, they rented a beautiful brownstone on Bainbridge Street in Bedford-Stuyvesant.

That Brooklyn rental, unbeknownst to Ashley Barnes, her husband, and their two school-age children, was part of a portfolio of single-family homes owned by a real estate investment trust, carefully acquired across the borough and the metropolitan area over the past decade.

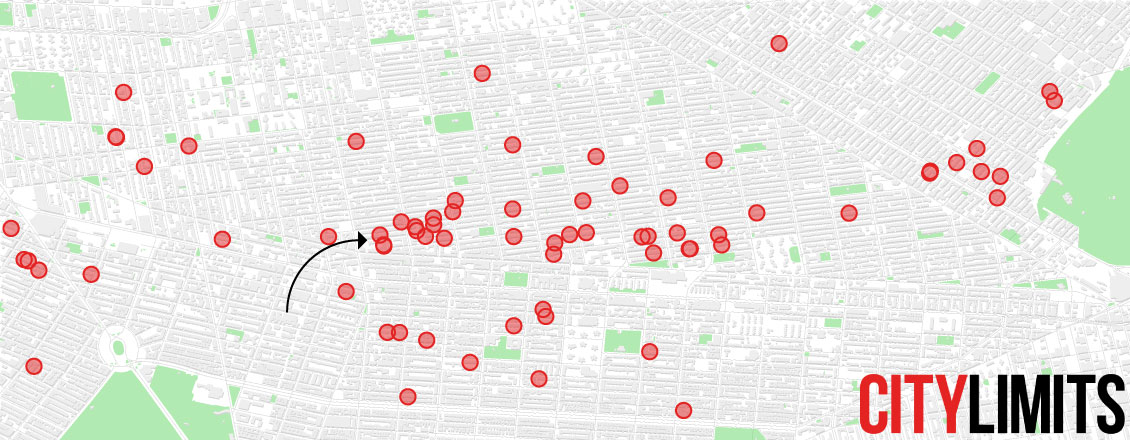

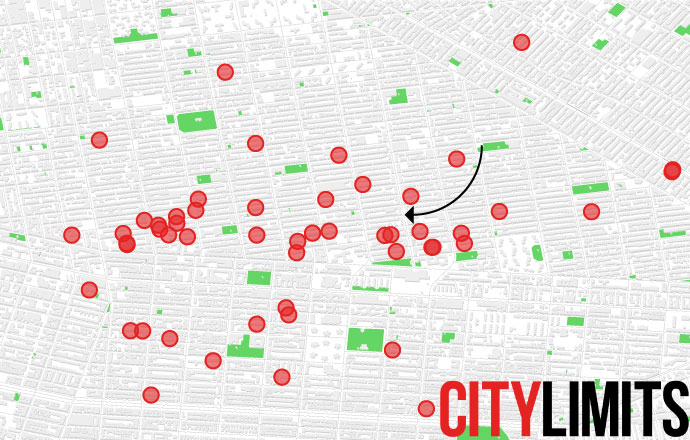

US Masters Residential Property Fund, a publicly-traded, Australian real estate investment trust (REIT), owns 479 properties across the New York City metro area, specializing in single-family, 1-4 unit homes. The biggest concentration is in the heart of brownstone Brooklyn, where they own 84 homes, 38 of them in fast-changing Bedford-Stuyvesant. The fund targeted, according to their website, “undervalued neighborhoods experiencing growth and gentrification.”

Betting on Brooklyn’s gentrification, however, has not fulfilled US Masters’ return goals. Their billion dollar real estate portfolio, which traded at over $1.50 a share from 2013 to 2018, now trades for just 30 cents. The fund is now looking to liquidate its single-family portfolio, per annual reporting and letters from the board on the company’s website and internet archives, leaving tenants in its dozens of Brooklyn rental properties facing an uncertain future, fearful that their homes will be sold out from under them and irritated by inconsistent management.

“I would be devastated to be perfectly frank,” Barnes said. “You go into renting knowing that that’s always a possibility… you might not be able to stay where you are.”

US Masters’s acquisitions and subsequent sell-off plans demonstrate the increasing complexity and financialization of New York’s real estate market as the city’s housing crisis persists, and how institutional investors can complicate tenancies and frustrate home-seekers.

An unusual investment strategy

Opportunistic investors have been buying up and renting out single-family homes in cities across the country since the 2008 financial crisis, capitalizing on the housing market’s big dip to acquire profitable rentals. Some trusts, like Invitation Homes and American Homes 4 Rent, won big in emerging urban markets in the South and Southwest.

US Masters tried to replicate that strategy in New York City, with little luck. New York City’s housing stock has long necessitated large institutional investors because of the city’s sheer costs: of property, transactions, and taxes.

In recent years corporate ownership of New York City real estate has ticked up among properties large and small, according to analysis by the nonprofit group JustFix. Even so, New York City hasn’t been the same hot spot for speculative real estate investment in single-family rentals as the Sunbelt.

Experts on real estate investment note that the biggest REITs tend to avoid markets like New York, due to high acquisition costs, high taxes, a stricter regulatory environment, and more tenant-friendly housing laws. Manon Vergerio, a researcher studying REITs, was surprised to hear about a trust operating in the city: “Maybe they are just clueless?”

US Masters did not respond to multiple requests for comment via email and phone.

Using data on land use, buildings, and property transfers from the city’s PLUTO and ACRIS datasets, City Limits identified purchasers of single-family homes in New York City from 2012 to 2022. Residential real estate investors often use a network of subsidiaries to buy and control assets.

By matching corporate entities based on a shared business address, duplicating a methodology used by JustFix, City Limits was able to link the sales activity of NY OAKLAND LLC and NRL URF LLC, two of the largest buyers of small homes in the city, to the US Masters Residential Property fund.

US Masters residential was the largest identifiable institutional investor operating a rental model for single-family homes at scale during the period City Limits examined.

Myrtle Avenue

Bushwick

Forte Greene Park

Bedford-Stuyvesant

Atlantic Avenue

US Masters Residential owns

38 properties in Bed-Stuy

Crown Heights

Eastern Parkway

Prospect Park

Myrtle Avenue

Bushwick

Bedford-Stuyvesant

US Masters Residential owns

38 properties in Bed-Stuy

Atlantic Avenue

Eastern Parkway

Crown Heights

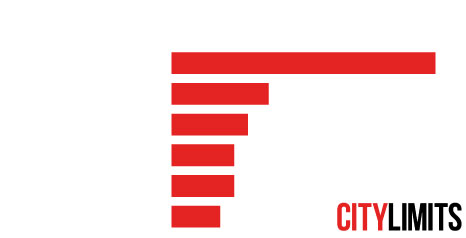

US Master’s Properties by Brooklyn Community District

38

Bed Stuy

14

Crown/Prospect Heights

Bushwick

11

Downtown/Brooklyn Heights

9

Park Slope/Carroll Gardens

9

Other Brooklyn

7

Above: A map of Brooklyn homes identified by City Limits as part of US Masters Residential Property fund. Graphic by Patrick Spauster.

In a 2021 letter, the US Masters’ board chair called the fund “unusual in its composition, location, and scale.”

Less than 3 percent of New York’s single-family tax lots are owned by institutional investors like REITs, trusts, and other corporate entities, and less than 2 percent of New York’s single-family tax lots are rentals.

Despite their small slice of the market, institutional investors made a disproportionate number of purchases of the single-family housing stock in the city, especially in gentrifying community districts. In Bed-Stuy, corporate investors made over half of the purchases of single family homes in the past decade, the highest share of any outer borough community district.

So while US Masters is just a fractional player in New York’s broader housing market, and tiny compared to other REITs operating in the United States, it has an outsized presence in the local single-family market. Most owners of single-family lots in the city own just one property. Yet US Masters, with over 100 properties citywide, owns more single-family homes than any other private owner in New York City, more than doubling the next largest owner.

There may be some upside to the strategy of investing in smaller rental properties. Vergerio notes that buildings with 1-4 units have fewer regulations. For example, rent stabilization and source of income discrimination laws carve out exemptions for smaller properties and those that are owner occupied. Even Good Cause eviction, the flagship tenant bill that progressive state lawmakers sought to pass in the most recent legislative session, would exempt small properties like those in US Masters’ portfolio.

“I’m not surprised that they would be looking at smaller family homes that are not subject to that type of regulation,” said Angela Stovall, the housing specialist at JustFix. “It might be more profitable for them to set those rents as high as possible, especially because they’re in these beautiful brownstones that are obviously very attractive.”

Adi Talwar

Adi Talwar

Adi Talwar

Adi Talwar

Brooklyn properties included in the US Masters Residential Property fund. Photos by Adi Talwar.

Single-family homes, scattered across the outer boroughs, might also be more difficult for tenants to organize. But that dispersed model also makes the properties harder to manage.

Property transaction data suggests that flipping might be the more common strategy for investors in smaller homes, rather than managing rentals. Among small properties that changed hands two times or more over the past decade, a quarter of them passed through an institutional investor.

Vergerio suspects US Masters strategy is to buy homes with some signs of disinvestment, renovate them, and “rent them out to gentrifiers at astronomical rents.”

To the extent the trust’s acquisitions have contributed to Bed Stuy’s gentrification, the damage may already be done. Bed Stuy has been losing Black residents for decades. In 2000, the neighborhood was 75 percent Black. According to 2021 American Community Survey data, Black residents now account for just 40 percent of the area’s population.

At least eight of US Masters’ Brooklyn properties were owned by individuals sometime in the past decade, according to property records data. Now, most of the multiple bedroom rentals list for over $5,000 a month.

Many of the current tenants in US Masters buildings who spoke to City Limits were young professionals, living with roommates and splitting exorbitant rents. Some families, like the Barnes, are paying big rents to live in a home large enough to raise a family and have space for parents and friends to come visit.

It can be hard to find family-sized housing in New York City at all, much less affordable family-sized housing. “We have a certain size home that we feel comfortable in for our family and there’s not many for rent in the area,” said Barnes.

“How are you going to compete?”

Barnes grew up spending time with family in Brooklyn, where her father is from. She and her husband moved to Bed-Stuy first in 2012, but left for New Jersey when they couldn’t afford to buy in the neighborhood.

They came back to Bed-Stuy in 2021 for a rental that had everything they needed: a backyard, walkable schools, and enough bedrooms for parents, two kids, and visiting relatives. “I love the block. I love what it means to me and my kids to live amongst our neighbors,” said Barnes, “we’re really happy here.”

Yet Barnes could feel the change from 2012 to now. “The things that I love the most about the neighborhood are being pushed out and you can feel it creeping across,” said Barnes. “I have mixed feelings about that… we are a Black family, but I wasn’t born and raised here.”

Some tenants were not shocked to learn that their home was owned by a trust. Two US Masters tenants in Bushwick, Luxu L and Xha S, who asked City Limits to withhold their full names, felt that it fit the trends they’ve seen in homeownership in New York. “That’s not surprising,” they chuckled. “We’re both from Queens.”

While not surprised, some tenants felt discouraged by the presence of the trust in the neighborhood. They lamented dealing with a faceless entity, rather than a landlord they know, though cited few issues with the trust and their management company, Dixon. Tenants largely reported liking their homes and found Dixon easy to contact. Work orders were completed swiftly and without fuss.

The more salient sentiment, however, was a feeling of being trapped between worlds. At once well-to-do enough to bear premium rents, US Masters’ tenants, fearing possible sales and rising rents, had little hope of being able to stay long term, much less afford a home in the neighborhood.

Michael Dadurian and his four roommates on Hancock Street saw rent jump nearly 30 percent in 2023, from over $6,300 to $8,400 dollars for a four-bedroom townhouse. Dadurian and his roommates probably won’t renew, they say, in part because of the rent hikes and changing life circumstances. Another tenant reported a 15 percent rent increase this year.

Owning their home was the Barnes family’s ultimate goal. “We talked about if they said it was going for sale, could we figure it out? And there’s just no way,” said Barnes. One US Masters townhome on MacDonough Street recently sold for $2 million. It last sold in 2013 for $500,000.

New York City has the lowest homeownership rate of any major city in the country, and it has stayed stubbornly low for decades. All cash buyers, more likely to be investors or high net worth individuals, are purchasing a record share of homes, locking out less well-off bidders who need the help of a bank mortgage.

Adi Talwar

Vasia Patov (29), Axel Martin (29) and Michael Dadurian (29) on the steps of their rental home in Bedford-Stuyvesant in April. The roommates said their rent jumped nearly 30 percent this year.Dadurian found it upsetting. “Knowing so many properties are not going back in the hands of people. How are you going to compete?”

Vergerio agreed. “Having institutional players come into the market and having homeowners compete with giant investors is really bad,” said Vergerio. “They can [pay] above what is being offered. In a place like Bed-Stuy where Black homeowners have been displaced really aggressively… you throw a big investment firm in the mix and that intensifies some of these dynamics.”

Selling off

The fund’s decision to liquidate the portfolio illustrates some of the perils of investing in New York’s complicated housing market, particularly when economic forces from the COVID-19 pandemic and inflation don’t cooperate. For tenants, it’s another scary, if unsurprising twist thrown at them in a frustrating rental market.

Beginning in 2019, US Masters moved towards selling properties off one-by-one in their 1-4 family portfolio. The pace of sales ticked up in the following years, per the fund’s annual reporting, with leadership citing the fund’s low yield compared to other institutional property exposures and its operating complexity, given the large number of small assets.

In March 2022, the fund secured a sale agreement of the entire 1-4 family portfolio, but with volatile interest rates early last year, the transaction fell apart, leaving the fund to pursue selling assets off individually. With interest rates persistently high as the Federal Reserve tries to curb inflation, 2022’s letter from the chair suggested the fund could seek purchases from all cash buyers. Such a buyer is more likely to be another investor than a family like the Barnes’s.

Even the portfolio’s high rents and low vacancy aren’t enough to cover costs. The fund has high operating costs compared to rental income, perhaps relying instead on the appreciating value of the portfolio’s homes to refinance on favorable terms or sell properties at a large gain. A housing market in turmoil and high interest rates, real estate experts say, will complicate sales, perhaps compelling the fund to sit tight.

Unable to offload in bulk, US Masters moved to cut costs. In January 2023, US Masters reached an agreement with Brooksville LLC and switched management companies from Dixon to Pinnacle City Living, a move that tenants say has worsened service. Tenants are frustrated with the lack of responsiveness, especially when they are paying such a premium on rent.

When a leak sprang in one US Masters townhouse this spring, tenants reported that Pinnacle City Living took weeks to fix it, leaving a gaping hole in their living room. Then the air conditioning went out for a month during a record-hot summer. This was just weeks after tenants say their landlord raised rent by over 10 percent (Pinnacle did not immediately respond to City Limits’ request for comment).

Adi Talwar

Homes along Hancock Street, Brooklyn.The Barnes family’s rent went up 3 percent from 2021 to 2022. This year it went up 9 percent. They reached out to Pinnacle City Living to negotiate, but received no response.

Potentially selling a rental property raises uncomfortable questions for tenants. Tenant advocates worry about landlords’ adverse incentives when they want to sell a property, like raising rents or withholding new leases to get tenants to move on.

“There’s definitely some precariousness,” said JustFix’s Stovall, speaking about potential changes in ownership during a tenancy. “If their lease is active the new owners would have to honor at least this term, but the terms of that lease could change if they are going to renew. It could mean a major price hike.”

One tenant even mentioned the management company tried to sell them the house they rented —not an unusual practice—but notable in light of US Masters’ struggles to offload their portfolio.

Tenants have come to expect the turnover and turmoil of New York’s rental market. Kevin Ramos, who lives in Bushwick with four roommates, thought he would have more time before the owner might try to flip his townhome: “I thought it would take a few more years for this neighborhood to get more expensive.”

New York’s housing market has grown so expensive and complex that a home can at once be an undesirable asset to an investor and too far out of reach for even relatively well-off home seekers. It remains to be seen whether US Masters will prove a cautionary tale for institutional investors eyeing undervalued neighborhoods, or a herald of more speculative investment to come.

In the throes of a housing affordability crisis that most acutely affects the city’s low income renters, the market’s perils now catch up with even the most well-off renters. Squeezed out of homeownership and into the city’s lower-rent neighborhoods, those well-off renters, under different circumstances, might find themselves living elsewhere.

But there’s just something about the brownstone. It captures the imagination of tenants, homebuyers, and even investors, it would seem.

Ashley Barnes feels so close, and yet so far from her dream. “I always had a place in my heart for brownstones,” she said wistfully.

With research assistance from Ola Topczewska and Kyle Tebo

3 thoughts on “A Real Estate Trust Bought Dozens of Brooklyn Brownstones. Now It Wants Out.”

The city should step in and offer to assist at least long term renters to buy these properties. City workers especially police, teachers and firefighters should be assisted in buying these homes.

Whatever you think of these investment trusts they see the future of NYC as bleak and want out now.

I was hoping that this was a simple case of “investors assess NYC’s future as bleak and want out now” since that could mean a buying opportunity for me. Unfortunately, reading through the company’s annual reports and media coverage this is as much an assessment of the local real estate market as Zillow’s abysmal stock performance in 2021 & 2022 (roughly -75%) is an assessment of the US housing marketing during that same time (roughly +15%).

The stock’s peak was in 2016 and experienced most of its loss pre-covid, since stabilizing with modest increase. What happened?

In Summary:

– The fund was initially pitched as a passive landlord portfolio with high yield (8%) and charged a high handling fee to new investors.

– In 2015/2016 the fund switched strategies from being a passive landlord with high cash flow to a property speculator that required a slew of expensive services in addition to investment management like “the responsible entity; administration and accounting; architecture, design and construction; property management and leasing; property acquisition and disposal; execution, structuring and arranging (capital raisings); and debt arranging” Dixon charged MASSIVE fees for all of this and fundamentally transformed the risk profile of the stock.

– The outrageous fees and increased risk structure was very publicly exposed by the Australian media which triggered a board takeover and de-risking strategy. https://www.afr.com/companies/financial-services/evans-dixon-model-under-scrutiny-as-stocks-plunge-20190606-p51v6s

– The stock drop from 2016 then stabilization in 2020 onwards is a result of the board/strategy takeover.

Here’s a great article from 2016 that tackles the ridiculous chinanigans by Dixon titled “US Masters Residential Property Fund: A magic pudding, just not for Investors” by Liam Shorte of EVISER https://smsfcoach.com.au/2019/06/07/evans-dixon-us-masters-residential-property-fund-urf-under-scruitiny-warnings-were-given-3-years-ago/

No buying opportunity, but an interesting scheme to read about.