“People are bringing it up, people are talking about it and thinking about what can be done, but I don’t know that that has translated very well into action yet,” said Victoria Sanders, research analyst at the New York City Environmental Justice Alliance. “We really want to see actions starting to play out.”

CLARIFY News

During late July’s heat wave, the Remsen Sarita Jean Older Adult Club hung an official cooling center sign on the fence of Clarendon Road Church to signal that their “cooling center” status had been activated.This story was produced by student reporters in City Limits’ CLARIFY News program: Zion Irvine, Teron Lewis, Emma Sweger, Kaila Tomlinson, and instructor Abigail Savitch-Lew

On the sweltering afternoon of July 28, in the basement of East Flatbush’s Clarendon Road Church, a few dozen people were gathered in a large, cool room.

Having finished a lunch of fish creole, okra with tomatoes, yellow plantains and yuca with onions, they were now practicing Zumba to upbeat music. 71-year-old Elizabeth Stanley, senior president of the Remsen Sarita Jean Older Adult Club, told City Limits she lived across the street and helped organize a variety of fun events for her fellow seniors, from birthday parties to “hat” day. “People come out to laugh and enjoy themselves,” she said.

That week, however, the senior center was also a government-designated “cooling center,” and was open additional hours that Thursday and Friday—from 9 a.m. to 7 p.m. instead of the usual 9 a.m. to 5 p.m.—and an additional day that week (Saturday from 10 a.m. to 6 p.m.) for anyone in the community in need of air conditioning.

“Some people, seniors like ourselves, some of them can’t afford air conditioners, so they need a place they can come cool off for a little while,” explained Stanley. “With this heat, a fan can’t do it.”

With record-setting heat globally this summer, along with red skies from Canadian wildfire smoke, many New Yorkers are looking for a place to take refuge from the increasing impacts of climate change. Some can stay home, turn on an air purifier and air conditioner, and they’re safe. For others, it’s an ongoing frustration: they don’t own air conditioners, or they want to avoid running up their utility bills. It can be especially tricky for senior citizens and children, who are among the most vulnerable to extreme heat.

RELATED READING: Bill Would Make More New Yorkers Eligible for Air Conditioner Subsidy

This is where government-designated cooling centers—neighborhood spaces with air conditioning where people can go, at no cost, during heat emergencies—become useful. Each year, the NYC Department of Emergency Management (NYCEM) partners with agencies, private companies, and nonprofits to make available more than 500 cool spaces across the city, according to NYCEM. When the temperature skyrockets, the official NYC cooling center map allows residents to search for sites in their area.

Yet not every cooling center on the city’s online map was working as expected during late July’s heat wave. On Thursday, July 27, the Oversight and Investigations Division (OID) at the New York City Council visited 24 cooling centers in vulnerable neighborhoods across the city, and found that four were either not open, didn’t exist, or were under construction, while 10 didn’t have a sign announcing their cooling center status.

Out of the eight library-based cooling centers OID visited, five didn’t have drinking water available, according to OID Director Aaron Mendelsohn. Also a bit confusingly, while the cooling center website said that senior centers on the list were only open to older adults, that turned out not to be the case with the senior centers OID visited.

Upon discovery, the OID team contacted the NYCSEM and let them know of these issues, and NYCEM responded swiftly to address them, Mendelsohn noted. Later in the summer, NYCEM, prompted by a note that had been made by the OID fieldwork, also helped to ensure a cooling center for the visually impaired received a braille sign, and committed to getting braille signs for other cooling centers that serve the visually impaired.

It’s not the first time the city’s cooling centers have faced questions. But as climate change worsens, people are beginning to realize the necessity of the program and are more invested in improving it.

“People weren’t really talking about [extreme heat and cooling centers] much even two years ago and now the conversation is much more robust,” said Victoria Sanders, research analyst at the New York City Environmental Justice Alliance.

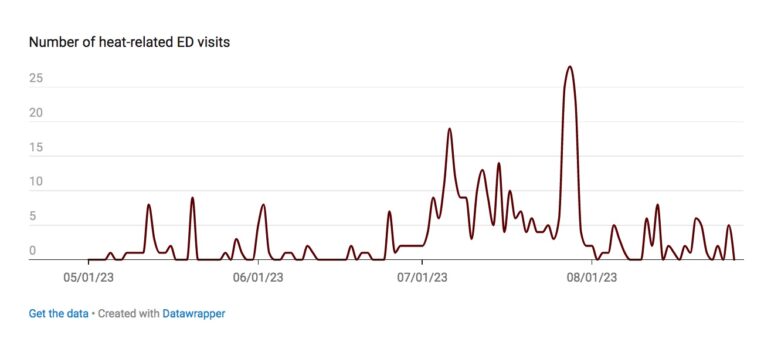

The passage of a 2020 law requiring the NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene to publish a detailed annual report on the number of heat-related deaths also helped to galvanize concern. According to the latest data, about 350 heat-related deaths occur each year in New York City—the vast majority not directly caused by heat stress, but by underlying conditions exacerbated by heat.

“People are bringing it up, people are talking about it and thinking about what can be done, but I don’t know that that has translated very well into action yet,” said Sanders. “We really want to see actions starting to play out.”

Ongoing concerns

As previously reported by City Limits, the city’s cooling center program faces some limitations.

First, as noted by Gothamist, the cooling center map tool only becomes available when the forecasted heat index (the estimate of how it feels when temperature and humidity are combined) reaches 95 to 99 degrees for at least two consecutive days, or over 100 for at least one day. Such a high heat index triggers a “heat advisory” that activates the city’s “heat emergency plan.” Some neighborhood advocates say that launching the website right before a heatwave doesn’t give residents—especially those who aren’t digitally savvy—enough time to know where they can go.

In addition, an analysis conducted in 2022 by Comptroller Brad Lander and covered by City Limits found that about 30 percent of centers closed before 4 p.m.—even though heat waves can last well into the evening—while half were listed as closed on Saturday and 83 percent were listed as closed on Sundays. The report also noted that about half the cooling centers were senior centers, potentially creating entry barriers for non-senior but still vulnerable populations (though it now appears not all senior centers disallow non-senior population visitors). In addition, 22 percent of the senior centers did not have wheelchair access.

Other studies by advocacy groups have shown further issues. For instance, a 2021 study by the nonprofit WE ACT for Environmental Justice that focused on upper Manhattan cooling centers found that less than half the sites had staff trained to identify heat-related illnesses, and 12.5 percent had staff who didn’t realize the building had a cooling center status. About 12.5 percent of centers looked at in the study didn’t have public restrooms, about 22 percent didn’t give out water, and 25 percent didn’t have any kind of programming or activities taking place for those present.

Citywide, cooling centers are unequally distributed, according to the Comptroller’s analysis, with Manhattan home to the highest access rate (7.1 centers available per every 100,000 people) compared to Queens, which had the lowest (5 per every 100,000 people).

When he was running for office in 2021, then-mayoral candidate Eric Adams linked to an article about cooling center placement inequities and tweeted that he would address the issue, if elected: “That’s completely unacceptable. We need to open more cooling centers in communities with vulnerable populations, immediately.”

Yet it remains unclear how much progress has been made to improve the program since Adams took office. Because the cooling center list is only available during heat advisories, it’s difficult to monitor changes to the program. City Limits’ request to NYCEM for the latest list of cooling centers from late July’s heatwave was denied.

“A list or database of cooling centers is not available because of different cooling centers operating on different days,” the office wrote to City Limits. “They are taken down or re-listed on an ongoing basis (this can be due to several factors including any equipment or staffing issues by the provider), therefore as a record there is no final version.”

NYCEM did, however, send City Limits its 2023 Cooling Center report, which includes a database of potential cooling centers “as of May 15, 2023,” each page marked “NOT FOR REAL TIME USE,” with the warning that the list “should not be used as a guide, nor should it be disseminated publicly.”

Cooling centers have a “very decentralized program operation,” said Louise Yeung, chief climate officer at Comptroller Lander’s office, a fact “that can pose some challenges to how the program is running and the consistency of service.”

Adi Talwar

A drinking fountain at Mount Hope Playground in the Bronx.Neighborhood-level inequities

According to the comptroller’s analysis, East Flatbush, Brooklyn is the worst served neighborhood, with a high “heat vulnerability index” score and the fewest cooling centers.

The city’s Heat Vulnerability Index (HVI) scores neighborhoods on a scale of one to five using a statistical model that calculates a neighborhood’s vulnerability to heat. The model takes into account factors including surface temperature, green space, access to home air conditioning, and percentage of low-income or Black residents (Black New Yorkers are twice as likely to die from direct heat stress as white New Yorkers, the result of systemic racism, environmental injustices and a range of related factors, according to Health Department data).

With an HVI of 5, East Flatbush has the highest level of heat vulnerability, but a rate of only 1.2 cooling centers for every 100,000 people.

“I want to increase cooling center locations in the district. I only have two!” said East Flatbush Councilmember Rita Joseph, who listed a number of ways she thinks the city can expand its cooling infrastructure, like establishing outdoor areas with fans, water sprays, and seating.

She also reiterated several of the the recommendations the comptroller’s 2022 made: expanding the hours that cooling centers operate—especially on weekends—making cooling center information permanently available to the public, ensuring all sites are ADA compliant, and transitioning to more sustainable cooling centers. She sees a local Boys and Clubs Club, places of worship, and schools as potential candidates for new cooling centers in her district.

In a response to a request for comment, NYCEM explained that it “prioritize[s] accessibility in establishing cooling centers” and that its “placement strategy involves comprehensive evaluation and close collaboration with community partners months in advance of the summer to ensure broad and widespread reach.”

“Despite our efforts, some gaps may still occur in areas in need of additional support, but we’re constantly striving to address these gaps to better serve all New Yorkers,” the agency’s statement said. NYCEM also encouraged community organizations interested in becoming cooling centers to fill out a Share Your Space Survey.

Access has improved for East Flatbush residents since the moment of the comptroller’s survey, the agency added. “At the time the Comptroller’s report was released, sites that are usually a part of the Cooling Center Program were under construction and were temporarily unable to open to the public,” an NYCEM spokesperson said. “In 2023, a library was able to rejoin the program after completing renovations and a new older adult center on the border of East Flatbush and Flatbush/Midwood joined the program.”

The “NOT FOR REAL TIME USE” map with a list of potential cooling centers as of May 15 showed three cooling centers within the East Flatbush community district’s boundaries, though it’s unclear if that represented on-the-ground conditions during July’s heatwave.

A dedicated stream of funding would help address inequities between neighborhoods, advocates say.

“Right now the budget for cooling centers is zero dollars,” explained Annie Carforo, climate justice campaigns manager at WE ACT. While some partner sites may benefit from government allocations from other agencies, like the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, for cooling center initiatives or at least for other functions, there is no funding stream from NYCEM for the cooling center initiative as a whole.

“Without a dedicated budget,” said Carforo, the cooling center program, “is not going to really serve people as well as it could.”

Sanders from NYC-EJA pointed out that because the partner sites are not funded for their roles as a cooling center, there is no mechanism for the city to hold them accountable or implement new rules, such as requiring a site remain open for additional hours.

When asked whether NYCEM agrees with the need for dedicated funding, the agency replied that it is “always open to feedback on our cooling center plans and are always improving our availability and operations.”

“Cooling center partners work diligently during heat activations to identify available staff to provide extended hours open for weekend activations,” an agency rep said. “During the July 2023 heat activation, over 200 older adult centers offered extended hours and opened on the weekend when normally closed to ensure communities across the five boroughs had access to a cool space. Spaces that want to provide extended hours on weekends or evenings should apply on the share space finder.”

Spreading the word

Vamel Baron, a 71-year-old Haitian native now living in East Flatbush, has air conditioning at home, but during the late July heatwave, he also saved some money by sitting under a tree on Nostrand Avenue. Asked if he’d heard of the Remsen Sarita Jean Older Adult Club a few blocks away, Baron said he knew of the place—he had been over to the address once for a Haitian Independence Day celebration—but he didn’t know the senior center also served as a cooling center for the community.

Lack of visibility may be limiting the program’s reach, stakeholders say. While the Remsen Sarita Jean Older Adult Club puts up a sign outside during heat waves and changes its voicemail to include cooling center hours during those times, many people learn about the site through word of mouth. Physical fliers and wayfinding signs are not required or provided by the city.

Christian Cassagnol, district manager for Queens Community Board 4, expressed concerns about lack of awareness, and particularly about the requirements needed for the cooling center website to go live. (Queens Community District 4 encompasses Elmhurst and Corona, which according to Lander’s report has the second-to-worst access to cooling centers, after East Flatbush.)

“Two consecutive days [of 95 degree weather] is just too much,” said Cassagnol. “We are really just playing with people’s lives.”

Although the board office sends out digital notifications to the community when cooling centers open, he thinks physical fliers might be better at getting the word out.

Carforo from WE ACT is also concerned that cooling centers can often be “really hard” to find, which she says contributes to underutilization. WE ACT would like to see the city implement wayfinding signs in the neighborhood directing people to the cooling centers, and making the centers themselves more welcoming destinations, with amenities like water, wifi, and charging stations, so that people feel comfortable there.

In his 2022 report, Lander joined WE ACT and others in taking issue with the city’s policy of leaving the cooling center finder offline except when there’s a heat advisory.

“While it is understandable that NYCEM wants to ensure accuracy of information and avoid confusion if cooling center locations or hours change, it makes it difficult for New Yorkers to prepare for heat waves in advance,” the report noted.

Asked for comment, NYCEM reiterated the importance of not posting a list of cooling centers because staffing and equipment are subject to change on any given day.

“Most libraries and older adult centers people are familiar with in their neighborhoods will be activated as cooling centers along with multilingual signage,” the agency said.

Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office

Workers in the New York City Emergency Management command center monitoring heat conditions on July 27, 2023.A new era of extreme heat management?

According to the New York City Panel on Climate Change, without action to mitigate climate change, New York City can expect to see the number of days at or above 90 degrees double by the 2050s. Facing this reality, some advocates and experts are spearheading visions for a revamped cooling center program.

According to WE ACT’s comprehensive 2023 Extreme Heat Policy Agenda, the environmental group is currently working with the New York City Council to put forth a bill that would officially codify the cooling center program. A first version of the bill was introduced in 2019, but never passed.

WE ACT envisions a revamped version of the legislation that would create a budget for the program through NYCEM, establish a minimum number of centers based on where vulnerable populations live, and improve education and advertisement about the centers.

It would also require the Health Department to conduct a survey of program utilization, and require organizations that receive funding be open for every heat advisory, put up certain signage, and train staff in identifying heat-related illnesses. The law would also ensure certain centers were designated as having extended hours, and create more desirable programming at the sites.

Advocates stress that the cooling center program is also only one small piece of a larger set of steps that must be taken to both adapt to the climate crisis, and to mitigate it. When it comes to extreme heat adaptation, Carforo also calls for increasing funding for the Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP), which provides and installs air conditioners for low income families and individuals. New York State set only $15 million this year for LIHEAP, and this fund has run out in early to mid-July for the past two years. Carforo states that the lack of funds is “a real abdication of responsibility by our government” and that there must also be funding for subsidizing electric bills.

Mendelsohn, from the City Council’s Oversight and Investigations Division, said they’re in conversation with Speaker Adrienne Adams’ office and Councilwoman Gale Brewer, chair of the Committee on Oversight and Investigations, about other ways to improve the cooling center program. OID would like to explore whether all public libraries used as cooling centers could have water stations available, and if some cooling centers could also be retrofitted into “clean air centers” to prepare for future air quality hazards, such as the wildfire smoke the city saw in early summer.

While the Council deliberates on possible policy changes, people in cooling center deserts continue to seek ways to cope. On Aug. 21, when the heat index was at 94 degrees—below the threshold for cooling center activation—a small group of men passed time in the shade of an outdoor structure on Nostrand Avenue.

“Cooling center” was not a term they’d heard before, but they agreed it would be nice to have more in the area. Asked what the government could do to help more people stay cool in the summer heat, they named portable ACs, fans, and water stations as something they’d like to see.

“There’s a lot they can do that they choose not to do,” one man said.