The developer and MTA have come to agreement on the platform needed for three towers, but Greenland USA won’t proceed without a key tax break. As Empire State Development floats proposals, watchdogs warn of delays.

Norman Oder

View west from Carlton Avenue showing the first railyard block, with three development sites, to be decked as part of the project. In the background is 18 Sixth Ave. (B4), the project’s largest tower so far, which flanks the Barclays Center arena.

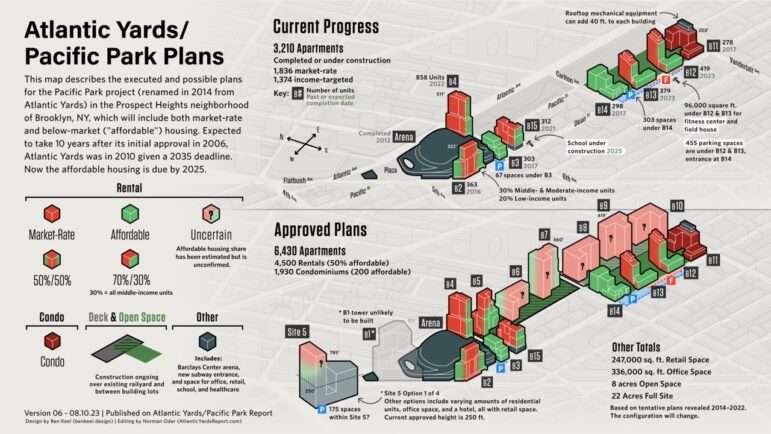

What’s next for the troubled Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park project in Brooklyn, which has seen just half of the approved 6,430 apartments built, and still needs major infrastructure investment—an expensive two-block platform over a working railyard—to complete the rest?

Perhaps some slack from New York State on the May 2025 deadline, by which the developer was supposed to deliver 876 more “affordable” units (out of a required 2,250) or face hefty fines, part of an agreement inked in 2014 around the massive development deal. The state may also intervene and recreate the crucial savings of the now-expired 421-a tax break.

The first element surfaced at a meeting Aug. 2 of the Atlantic Yards Community Development Corporation (AYCDC), which advises the parent Empire State Development (ESD), the gubernatorially controlled state authority that oversees and shepherds the project.

Some AYCDC directors, plus two local elected officials at the meeting, were skeptical that ESD’s proposed “community engagement process” regarding the project’s future could be taken seriously when the state has not enforced previous promises, like fines for the missing “Urban Room” atrium at what is now the Barclays Center plaza.

The bigger news surfaced later, when The Real Deal reported that ESD was considering a substitute for the 421-a tax break—seen by developer Greenland USA as key to future housing construction—just as Gov. Kathy Hochul recently proposed for projects in Gowanus.

An ESD spokesperson later confirmed that payments in lieu of taxes (PILOTs) “are being considered for the project.” If that happens, expect debate about whether Greenland deserves slack on the housing deadline for a project delayed multiple times, as “affordable” units grow more costly.

The 22-acre, 17-building Atlantic Yards was announced in 2003, approved in 2006 and re-approved in 2009. By 2014—after original developer Forest City Ratner had built the arena and started one tower—Greenland, part of a Shanghai-based firm, bought a majority share, changing the name to Pacific Park Brooklyn. Since then, seven towers have risen: three with Forest City, one with another developer, and three on sites leased to other developers.

Graphic by Ben Keel and Norman Oder

Moving forward?

At the meeting, held at ESD offices in Manhattan, a Metropolitan Transportation Authority official said the MTA and Greenland had resolved their differences related to building the first platform phase over the MTA’s Vanderbilt Yard, where the Long Island Rail Road stores and services trains using Atlantic Terminal.

The two-phase platform would enable six towers and fulfill the project’s eight acres of open space by adding five more. But looming is the 2025 affordable housing deadline negotiated in 2014, which comes with $2,000 a month fines for each unfinished unit.

The MTA had previously been cited by ESD as the roadblock to platform construction. Greenland in late 2019 claimed it would start the platform in 2020. In spring 2022, Greenland—which now owns nearly all of Greenland Forest City Partners going forward—said it was prepared to start, but didn’t proceed.

Then came the June 2022 expiration of the state’s controversial 421-a program, which offered property tax breaks to developers that build new housing. Only one railyard tower, B5, had foundation work started and could qualify for the tax break deadline, if finished by June 2026.

At the meeting, when asked for an anticipated start date for the 36-month buildout of the first platform block, Greenland hedged.

“There is no affordable housing subsidy in place for this project,” Xinmei (Macy) Wang, a Greenland executive based in Los Angeles, said over the phone, indicating 421-a, “so we are evaluating how to proceed.”

Other potential factors include high interest rates, rising construction costs, and parent Greenland Holding Group’s near-default credit rating and limited liquidity. (The company is based in China, where the real estate market is currently in crisis.) The trainyard platform could cost more than $300 million, at a time when Greenland USA is also trying to extend payments on $349 million in low-cost EB-5 loans from immigrant investors.

Joel Kolkmann, ESD’s senior vice president of real estate and planning, then changed the subject, as if prepared to deliver the meeting’s most important news: He noted that, at a previous AYCDC meeting, ESD’s then-Project Director Tobi Jaiyesimi cited plans for public engagement regarding the project’s future, including the affordability of housing.

That process could delay plans to meet the 2025 affordable housing deadline, some attendees worried, and perhaps lead to an extension, given ESD’s unwillingness to commit to enforcing it.

Greenland seemed on board.“With the beginning of the public engagement that ESD is going to lead, we hope to have a clearer picture of the timing and what we’ll build when we build,” executive Joshua Cohen said.

(Later sent a list of specific questions from City Limits, a spokesman for Greenland said the company would have no comment beyond what was said at the meeting.)

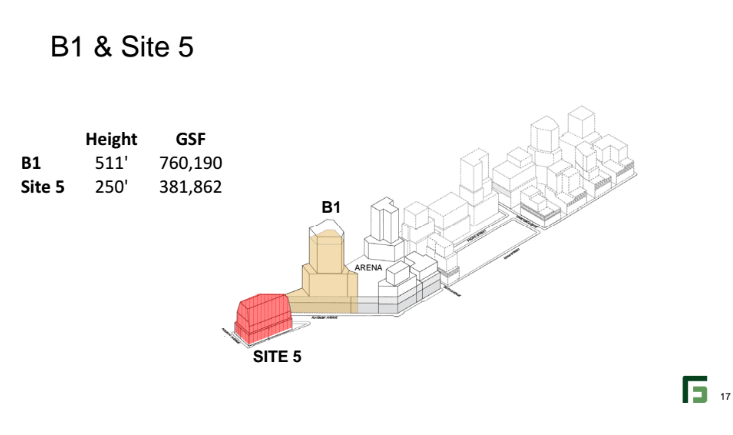

Source: 2016 presentation by Greenland Forest City Partners.

B1 and Site 5, as approved.

Adding Site 5

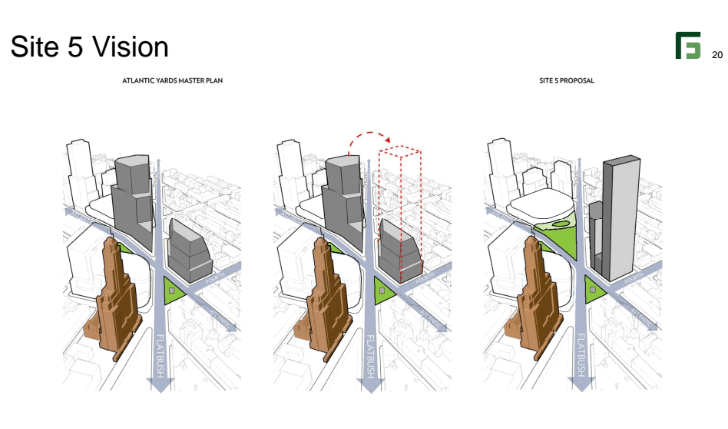

That process would involve not just the railyard towers, but the plan, floated by the developer in 2016, to shift the bulk of the unbuilt flagship tower—designated “B1” and once slated to loom over the arena—across Flatbush Avenue to Site 5, longtime home to two big-box stores.

A substantial building has already been approved for Site 5, a parcel bounded by Atlantic, Flatbush, and Fourth avenues, as well as Pacific Street. But shifting most but not all of the bulk would preserve the sponsored Barclays Center plaza, crucial to arena operations, and could create a much larger two-tower project.

That bulk shift would require, beyond initial public engagement, an approval process lasting a year before ESD’s parent board—typically a rubber stamp for the governor—amends project documents.

ESD’s Kolkmann said the public discussions would focus on affordability. Indeed, the income-targeted units that have opened so far are much more costly than promised, though affordable housing was a key selling point for the initial approval of the project, which was dogged by controversy over scale, subsidies, and the use of eminent domain.

While Forest City in 2005—via an overhyped Community Benefits Agreement (CBA)—promised to balance low-and middle-income “affordable” apartments, of 1,374 below-market units built, 1,054 serve middle-income households. The two-tower 595 Dean offers 240 income-linked units to households earning 130 percent of Area Median Income (AMI), mostly well over $100,000. The 93 one-bedroom apartments rent for $2,690, well below market-rate units there but hardly serving those who rallied for affordability with the advocacy group ACORN nearly two decades ago.

Not only was the CBA unenforceable, the state’s guiding contract allows a loose definition of “affordable”: any below-market housing in a government regulatory program. Moreover, delays in the project have coincided with rising AMI, the base for affordability calculations.

Though B1 was proposed as an office tower, a bulk shift to Site 5 could add hundreds of apartments. The buildable square footage might be worth $300 million, at least before factoring in affordable housing. So the affordability levels may relate to not just available subsidies and tax breaks, but also the state’s willingness to pressure the developer.

Source: 2016 developer presentation.

Proposal to shift bulk from B1 to Site 5, The Williamsburgh Savings Bank tower, now known as One Hanson, is in the foreground.Some pushback

While Kolkmann said project documents haven’t changed, he deflected a question about enforcing that 2025 housing deadline. Should Greenland fail to deliver, the fines could total $1.75 million a month, directed to an affordable housing trust fund. The project’s guiding Development Agreement allows a delay based on the unavailability of subsidies, though it’s unclear that the loss of 421-a qualifies.

“If the construction of affordable housing is on hold pending an authorization of a new subsidy,” AYCDC Director Gib Veconi asked at the meeting, “is the developer prepared to make good on the liquidated damages?”

Veconi, a leader in the BrooklynSpeaks coalition that in 2014 negotiated the housing deadline, didn’t get an answer. “We can do public engagement,” he added, “but if we’re promising something in the future and we haven’t even been able to enforce the remedies for what we promised in the past,” it won’t be effective.

He was backed by Assemblymember Jo Anne Simon and State Sen. Jabari Brisport, both present at the Aug. 2 meeting.

AYCDC Director Ron Shiffman, a veteran community planner and Pratt Institute academic, warned that public engagement should not be used to delay the project and to avoid improving affordability.

Veconi again asked if Greenland would pay the fines. If so, “we can talk about doing something like community engagement… but if you’re not, then we’ve got to have a different discussion,” he said.

AYCDC Acting Chair Daniel Kummer intervened. “I don’t think we can expect them [Greenland], on the phone, to answer the question directly,” he said, “but I think they should take the question very seriously under advisement.”

AYCDC Director Ethel Tyus warned about reinventing the wheel with engagement, noting that 35th District Council Member Crystal Hudson, whose district includes most of the project site, has already conducted several land use sessions focusing on a proposed rezoning around Atlantic Avenue nearby.

ESD Executive VP Arden Sokolow responded that the proposed public sessions were not intended “to distract or delay.”

“This is truly born of a heartfelt desire to talk about these issues,” including AMIs being served, Sokolow said.

Greenland does have incentive to build: since 2016, it’s been paying the MTA $11 million a year for development rights over the railyard, and must pay through 2030 to gain control of the six sites. Those payments fulfill a 2009 revision of the initially pledged $100 million payment for development rights.

Another scenario, though, worries some observers: could Greenland, after gaining approval for the bulk shift, sell a shovel-ready Site 5 to another developer, recouping some of its expenditures, and leave the platform and railyard sites in limbo? (The company declined to comment when City Limits asked if this was a possibility).

At the meeting, Veconi said that, as a precondition to public discussion, the AYCDC should see a financial analysis of the project’s future, including funds needed to pay liquidated damages.

The advisory board asked the parent ESD to deliver such a report by Oct. 3.

To reach the editor behind this story, email Jeanmarie@citylimits.org.