The bills were part of a larger legislative package related to rules around lead paint, and advocates are hoping to see the City Council bring related bills to a vote by the beginning of August.

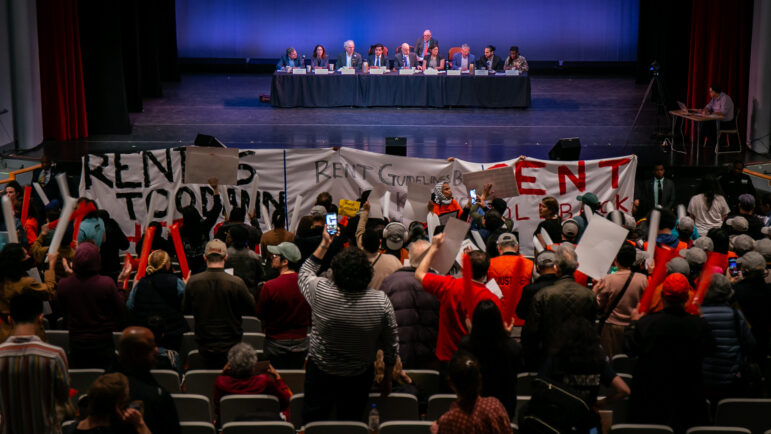

Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography

Former Mayor Bill de Blasio and officials show off a lead paint testing device at a press conference in 2019.The City Council on Thursday passed two bills that intend to close loopholes around lead paint enforcement and bring the city closer to its goal of ending childhood lead poisoning—though advocates hope to see lawmakers pass additional reforms in the coming weeks.

Intro. 193, sponsored by Councilmember Carlina Rivera, will make peeling or chipped lead-based paint a class C immediately hazardous violation in common areas of buildings where a child under 6 resides.

Intro. 200, sponsored by Councilmember Rafael Salamanca, will require the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH) to publish biannual reports on objections filed by building owners in response to the city’s lead abatement orders, including objections filed by the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA).

A third bill, Intro. 1025, aimed to assess children with elevated blood lead levels for eligibility for special education services, but the City Council withdrew the legislation from its agenda on Wednesday due to concerns from advocates. The bills were part of a larger legislative package related to rules around lead paint, and advocates are hoping to see the Council bring the three remaining items to a vote by the beginning of August.

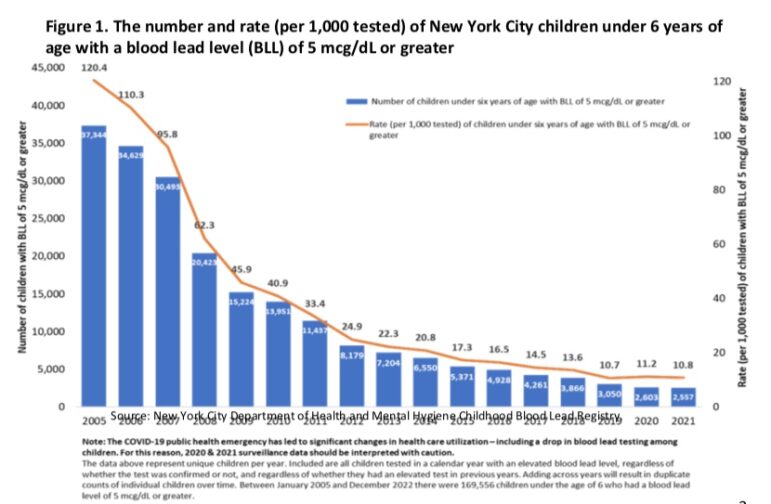

According to a 2022 report by the DOHMH, 2,557 New York City children aged 6 or under were tested to have blood levels of 5 micrograms per deciliter (mcg/dL) or greater in 2021, the threshold at the time that would trigger an investigation from the city.

Of those children, 88 percent were from moderate- to high-poverty neighborhoods. Asian, Black and Latino children also represented 81 percent of children under age 6 who were newly identified that year to have elevated blood lead levels. This spring, DOHMH adopted a stricter standard, lowering the threshold that sparks an investigation to 3.5 mcg/dL.

DOHMH

“We have a responsibility as elected officials to protect New Yorkers from toxic exposures that poison our communities, primarily communities of color, low-income families, and immigrants,” Rivera said. “Without adequate enforcement, our communities are quite literally being left in the dust.”

Under Rivera’s bill, property owners must immediately address peeling or chipped lead paint found in common areas of buildings with multiple dwellings—such as hallways, staircases, and lobbies. The bill also instructs inspectors from the Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD) to conduct visual inspections of common areas that are on their paths to inspect apartments in buildings constructed before 1960 where a child under 6 resides.

The legislation initially required HPD inspectors to examine all common areas in such residences during their inspections, which received pushback from the city agency.

AnnMarie Santiago, a representative from HPD, voiced her opposition to the bill during an April hearing on the broader legislative package.

“The resources that would be required for HPD to inspect, issue violations for, and correct peeling paint in public areas would be one of the largest new needs HPD would face, and raises concerns about focusing resources on an area which will not yield a high return in terms of the impact on reducing exposure,” she said.

Frank Ricci, executive vice president of landlord group the Rent Stabilization Association, likewise testified against the legislation in the hearing.

“Really, it’s a misdirection of resources,” he told City Limits, stressing the high cost of X-ray fluorescence testing, which is used to detect the presence of lead. “That money could be better spent on units people actually inhabit and removing the lead hazards there.”

The second bill passed by the City Council, Intro. 200, is a “common sense bill” that aims to increase accountability, Salamanca said.

He said that through hearings, the City Council discovered that NYCHA—which was found to have for years failed to conduct mandatory paint inspections—was appealing the majority of the Health Department’s lead abatement orders. “It created a backlog, and things started slipping through DOH’s hands. We said that we needed to have more teeth to this oversight, and so that’s where the idea of the bill came from,” Salamanca said.

“We’re trying to bring a level of transparency here from both sides,” he added.

Intro. 1025, which was initially expected to come up for a vote before being pulled by the City Council on Wednesday, would have required the DOHMH to request that any child with elevated blood lead levels be referred to the Committee on Special Education of the Department of Education, which would then determine if the child qualified for special education services.

But the final version of the bill differed significantly from the original, according to advocates. Whereas the initial bill mandated a nueropsychogical or neurodevelopmental evaluation by the DOE, for example, the version set for Thursday’s vote required the child to receive only “an initial evaluation.”

The amendment concerned WE ACT for Environmental Justice, a member of the New York City Coalition to End Lead Poisoning (NYCCELP), according to WE ACT’s New York City Policy and Advocacy Manager Lonnie Portis.

“The psychological evaluation captures more than just the standard test that is given,” he said. “We wanted to really take a look at that language to make sure it was doing what it was supposed to do.”

Strict New York State laws concerning special education placed restrictions on the Council’s bill, forcing councilmembers to alter its language throughout the legislative process, explained Councilmember Lynn Schulman, the bill’s primary sponsor. “We did the best we could,” she said. “But advocates were really upset.”

Schulman added that she and health advocates are reviewing possible courses of action together, which include proposing a resolution to state legislation instead of attempting to rescue Intro. 1025.

Portis said that advocates are also turning their attention to three other items—Intros. 5, 6, and 750—which intend to close more loopholes in the city’s Local Law One of 2004, known as the Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention Act. Intro. 5 concerns records of lead-based paint investigations, Intro. 6 addresses the removal of lead-based paint on friction surfaces, and Intro. 750 relates to proactive inspections of dwellings where children remain at risk of lead poisoning.

“This legislation really builds on decades of progress, and we know there’s more to do, so I’m looking forward to working with colleagues and advocates,” Rivera said. “We have to do everything we can to protect New York’s children from harmful impacts of lead exposure.”