“Extreme heat is not an isolated issue. It is intertwined with other injustices like urban development and racist infrastructure,” said Rami Dinnawi, a representative from the community human rights organization El Puente de Williamsburg. “We need to support community-led initiatives on mitigating the effect of extreme heat.”

CLARIFY News

Advocates rallied in City Hall Park Thursday calling for the city to come up with a plan to address extreme heat.This story was produced by student reporters in the City Limits Accountability Reporting Initiative For Youth (CLARIFY).

By Shanyll Nunez, Alana Allen, Sangeeta Chakraborty, Fatoumata Conde, Kayla Hall, Soleil Hendy, Zion Irvine, Hamna Kanwal, Teron Lewis, Ilana Livshits, Maleea Mcphatter, Jillian Peprah-Frimpong, Emma Sweeger, Robert Vanterpool, and instructor/editor Abigail Savitch-Lew

On Thursday at City Hall Park, environmental groups, community based organizations, and political representatives held a rally demanding action to address the impacts of extreme heat—while meanwhile, across the street, other politicians announced a package of bills aimed at regulating indoor air quality.

The two outdoor gatherings unfolded on yet another humid, sweltering day in the city, with a “moderate” air quality index rating. Advocates and concerned policymakers say the city must take more steps to protect New Yorkers from the worsening effects of climate change, whether that’s boiling temperatures or smoke from faraway wildfires.

“This is a legacy issue, this is a public health emergency, and we’re counting on the mayor to help us in this fight,” said Councilmember Lincoln Restler at the extreme heat rally.

Councilmember Keith Powers, who was about to introduce legislation to improve indoor air quality, proclaimed, “We are here today to help New Yorkers breathe a little easier.”

Extreme heat is an equity issue

Dozens of people—with many more gathered as audience—raised their voices in City Hall Park to chant, “What do we want? Climate justice! When do we want it? Now!”

Many were members of WE ACT, a longstanding environmental justice organization based in Harlem. WE ACT was joined by other community organizations such as GOLES, New Yorkers for Parks, the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), El Puente, Red Hook Initiative, and South Bronx Unite, according to a press release.

Speakers expressed concerns about inadequate infrastructure and a lack of access to cooling resources. They also stressed that extreme heat impacts communities of color and low income communities differently.

According to statistics from the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH), Black New Yorkers are more than twice as likely to die from extreme heat. Compounding factors—the history of redlining and disinvestment, lack of access to health care, lack of green spaces, and more—means neighborhoods in the South Bronx, Harlem, East Brooklyn, and Jamaica score highest on the “heat vulnerability index.”

“Extreme heat is not an isolated issue. It is intertwined with other injustices like urban development and racist infrastructure,” said Rami Dinnawi, a representative from the community human rights organization El Puente de Williamsburg. “We need to support community-led initiatives on mitigating the effect of extreme heat.”

Bronx advocates agreed.

“In the Bronx, we need urgency and immediate action,” said Clean Air Program Coordinator Leslie Vasquez of South Bronx Unite, adding that the Bronx has one of the highest asthma rates in the country. “Our communities can no longer suffer!”

Last week, WE ACT released its 2023 Extreme Heat Policy Agenda, a roadmap with eight objectives to protect vulnerable communities from extreme heat, and the organization also announced the formation of a statewide Extreme Heat Coalition.

At an online press conference on July 6, WE ACT noted that New York City is especially vulnerable to rising temperatures due to the dense concentrations of pavement, buildings, and other surfaces that absorb heat instead of reflecting it (what’s known as the “urban heat island” effect). They also described their advocacy for a range of policies and bills on the federal, state, and city level.

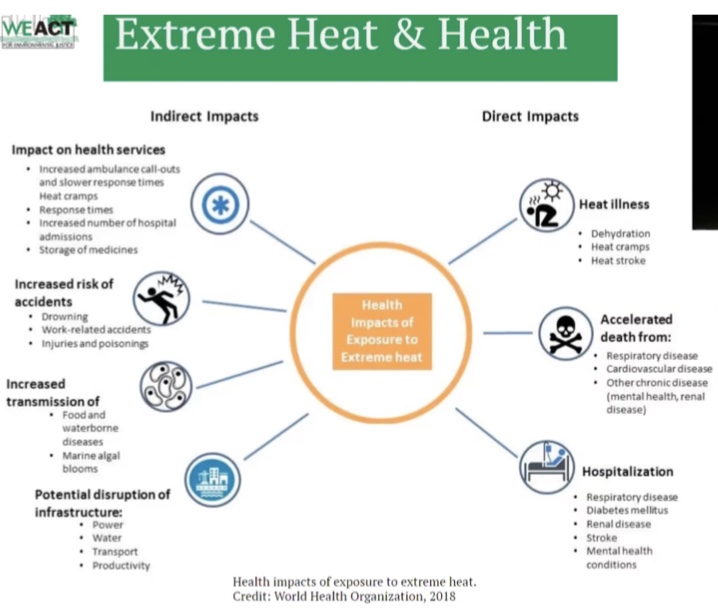

Screenshot

A recording of WE ACT’s 2023 Extreme Heat Briefing shows a graphic from the World Health Organization illustrating health impacts of exposure to extreme heat.Among many other recommendations, WE ACT calls for increasing state funding for the Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP) to make it easier for low-income households to run air conditioners. They also want to pass legislation in the City Council to impose strict limits on how hot it can get inside of buildings.

Furthermore, they’re calling for resources to grow and maintain urban forests and advocating for the expansion of green infrastructure such as cool pavements, cool roofs, green roofs, and renewable energy, both to help cool vulnerable neighborhoods and to naturally decrease New York’s carbon footprint. Several parts of their roadmap have een proposed as bills by the City Council.

Advocates are also calling on the City Council to hold New York City Mayor Eric Adams accountable for fulfilling the extreme heat goals his administration laid out in PlanNYC.

“We need the mayor to make this one of his priority issues,” said Eric Goldstein, NYC environment director at NDRC.

Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office

Smoke from wide fires in Canada blurring the New York City skyline on Tuesday.Smoke behind closed windows

Meanwhile, Councilmember and Majority Leader Keith Powers and Manhattan Borough President Mark Levine held a press conference to announce an indoor air quality legislation package consisting of four bills.

Intro 1127 would require the Health Department to set standards for air quality in schools and the Department of Education (DOE)—with the assistance of the Department of Environmental Protection (DEP)—to monitor and report on real time air quality in schools on the DOE website, as well as issue annual reports about school air quality. It would also require DOH and the DOE to engage in outreach and education about indoor air quality in schools.

Intro 1130 would make similar requirements but for city owned buildings, while Intro 1128 and Intro 1129 would create pilot programs to monitor indoor air quality in certain commercial and residential buildings, respectively.

“I believe personally that this is an issue nationwide that we are ignoring,” said Keith Powers, noting that both the recent wildfires and the COVID-19 pandemic have made us all more aware of indoor air quality. “The data collected … will help us inform best practices,” he added, saying he envisions New York City becoming a national leader in indoor air quality regulation.

Borough President Levine described working in his office on the 19th floor of 1 Centre Street and smelling smoke—even though the windows were all sealed—during the recent air quality crisis caused by Canadian wildfires. “What we’re doing with this package of bills is a major first step,” he said.

Others who spoke in support include Councilmember Lynn Schluman, chair of the Committee on Health, Councilmember Rita Joseph, chair of the Education Committee, and Councilmember Mercedes Narcisse, chair of the Committee on Hospitals, who stressed the importance of protecting vulnerable communities and ensuring “that the community is alert” to air quality changes as they happen.