Last season, the city’s 25 beaches saw a total of 244 closures, either because water quality exceeded the city’s safety standards—determined by testing for the bacteria found in fecal matter—or because of excessive rainfall, which increases the likelihood of pollution entering local waterways. That’s up from 94 such closures during the 2021 season.

Beach season has arrived as New York City officially opened its waterfront for swimming on Memorial Day weekend.

But in a city where billions of gallons of sewage and stormwater runoff are discharged into local waterways each year, swimmers around the big apple may want to check the water quality at their local beach before diving in headfirst, environmentalists say. On Thursday, for instance, a day before it was set to reopen for the season, city officials warned swimmers to avoid south Brooklyn’s Manhattan Beach, citing “inadequate water quality.”

“If you’re going to be swimming in [New York City], you’re going to want to know what’s in that water. And once you do know, you’re going to want to do something about it,” said Deanne Draeger, founder of Urban Swim, a non profit organization dedicated to providing safe access to clean water.

City Limits reviewed public data for the past four summers and found that last season alone, the city’s 25 beaches saw a total of 244 closures, either because water quality exceeded the city’s safety standards—determined by testing for the bacteria found in fecal matter—or because of excessive rainfall, which increases the likelihood of pollution entering local waterways. That’s up from 94 such closures during the 2021 season.

Poor water quality in New York City’s beaches stems mostly from raw sewage that overflows from the city’s outdated sewer system, and pollution from the streets that makes its way into the harbor when it rains, environmentalists who spoke with City Limits say. The degree to which each form of contamination affects a particular beach depends on location—some are closer to sewage overflow sources than others.

Officials say the city’s waterways are the cleanest they’ve been since the Civil War. Government agencies have poured billions of dollars into replacing pipes and funding infrastructure projects designed to intercept stormwater before it reaches the sewer system. But climate change has ushered in heavier rains, causing more sewage and pollution to spill over into the surrounding harbor and rivers.

The Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) estimates that 11 billion gallons of raw sewage mixed with polluted runoff gets discharged into the surrounding waters annually. Environmental groups, however, believe the true figure is actually worse, and project that New York City waters receive 20 to 30 billion gallons of the discharge every year.

“It’s sewage mixed with stormwater untreated,” said Peter Linderoth, director of water quality at the environmental non-profit Save the Sound. “That’s going to be a major stressor on any swimming beach in the area.”

What the numbers show: private vs public beaches

Beaches can be shut down if sampled water has enough bacteria in it to exceed a threshold defined by the state as having a higher risk of making people sick. Bathing in contaminated water can lead to rashes, infections and intestinal issues, according to the city’s health department (New Yorkers can get updated advisories before they hit the shore by calling 311 or texting “Beach” to 55676.)

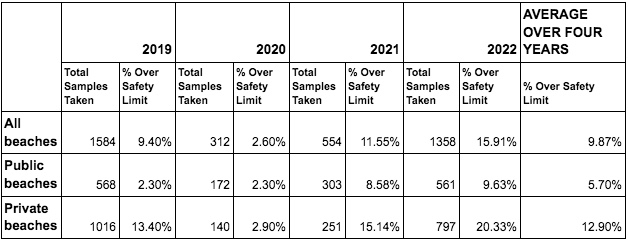

While the number of water samples tested has varied greatly from one year to the next, the percentage of tested samples exceeding the safety limit has crept up each year since 2019 for both private and public beaches, with the exception of the pandemic summer of 2020, when very few samples were taken.

NYC Dept. of Health

Over the past four summers, the city’s private beaches consistently displayed the poorest water quality compared to public swimming spots. Most private beaches are located in harbors of semi-enclosed land where contaminated water remains stagnant.

Meanwhile, the majority of public beaches popular with swimmers and sunbathers face open ocean water, where currents consistently flush out contaminants. Over the last four summers, just under 6 percent of water samples tested at the city’s eight public beaches were over the safety threshold. Some have displayed great water quality, like Rockaway Beach, where water samples didn’t exceed the threshold at all in three out of the past four years.

But one private beach in particular, Douglaston Manor Association in Queens, consistently had more samples exceeding the city’s safety limit than any other beach four years in a row. In 2021, 50 percent of tests exceeded the threshold. Last year, it clocked in at over 45 percent.

Other beaches that stood out for exceeding safety limits in 2022 were private beaches White Cross Fishing Club in the Bronx, with over 40 percent of its samples exceeding the threshold, and Whitestone Booster Civic in Queens, with more than 35 percent of samples over the limit.

Different sewers, different problems

In New York City, 60 percent of sewers use an archaic combined system designed in the 19th century to collect both wastewater and storm runoff in the same pipes. During heavy rains, the pipes cannot handle the amount of water coming in, forcing them to dump waste into the nearest water body without treatment in a process known as Combined Sewer Overflow (CSO).

“So it’s no mystery what causes the water quality to be worse after rain. It’s sewage from eight and a half million people,” explained Dan Shapley, the senior director of advocacy, policy and planning at the environmental non-profit Riverkeeper.

Most modern cities have moved away from using this model and today less than 4 percent of U.S. municipalities still have them. But separating the city’s combined sewer system is not a viable solution because it would cost well over $100 billion, the DEP told City Limits.

Meanwhile, beaches like Douglaston Manor Association in Queens get hit with the overflow of sewage that gushes out of these pipes during storms. Save the Sound’s annual beach report, which compiles beach data from agencies all over New York and assigns them a grade from A to F, ranked Douglaston as the worst beach in the state in its most recent 2021 report.

The Open Sewer Atlas, an interactive map of the big apple’s sewer system launched by the non-profit New York Soil and Water Conservation District, shows that Douglaston is located near a combined sewer discharge point or an “outfall.”

This outfall discharged 105 million gallons in 2016, according to the most recent data featured on the map. In that year alone, the waste overflowed there more than 14 times, and only 0.76 inches of rainfall was needed to trigger the overflow of the combined sewer system, according to the map.

“My guess is that there are probably more discharges happening [now] because we tend to have heavier rain events. And when rain happens, sometimes it just dumps in a very short period of time,” said Shino Tanikawa, executive director of New York City Soil & Water Conservation District.

To top it off, Douglaston beach is located in Alley Creek, a natural wetland area that has been of particular concern to the environmental community because of past industrial pollution.

Pollution is a main issue when it comes to poor beach water quality. Rain often carries chemicals, fast food wrappers, cigarette butts, oil, bacteria from pet waste and other kinds of debris from New York City’s streets and rooftops into its harbor.

Adi Talwar

A Municipal Separate Storm Sewer System outfall on the west shore of Sheepshead Bay in Brooklyn.In some parts of the city, this storm runoff doesn’t end up in the city’s combined sewer system. Instead, it gets funneled into separate pipes called the Municipal Separate Storm Sewer System (MS4). This water doesn’t get treated because it isn’t connected to wastewater treatment plants.

Wolfe’s Pond Park is a public beach in Staten Island—a part of the city that relies solely on the MS4 system—that over recent years has seen an increase in sampled water exceeding the city’s safety threshold.

Two years ago, 22 percent of the water tested at Wolfe’s Pond beach exceeded the city’s safety threshold. NYC’s Beach Report attributed this spike to “excessive flooding from multiple tropical storms (Elsa, Ida, and Henri) that impacted the New York City shoreline.”

But last year, Wolfe’s Pond Beach saw another spike: 28 percent of its sampled water exceeded the safety limit determined by the city.

The DEP told City Limits that Wolfe’s Pond has failed to meet water quality standards due to combined sewer overflows coming in from New Jersey, and added that large flocks of birds could also be contributing to poor water quality there.

Handling the problem

The environmental community has a long history of pushing New York City officials to tackle its sewage overflow problems. In March of 2012, the city committed to doing something about it by signing what they called “a groundbreaking agreement” to reduce Combined Sewer Overflows.

From there, the state-wide Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) and the local DEP set out to develop 10 Long-Term Control Plans, which would zero in on the different bodies of water around the city and come up with solutions to the sewage problems specific to each region.

But it’s taken over a decade to get these plans up and running. The proposal for Alley Creek, for instance, was submitted in the summer of 2013, but only got approved in March of 2017. While DEP says it’s on track with commitments made for Alley Creek, the plan is ongoing.

“Riverkeeper is convinced that the city and the state are really not doing enough and not fast enough to reduce [sewage] overflows,” said Shapley. “So we will see these water quality conditions for another generation if we don’t pick up the pace and require more of the city.”

The DEP told City Limits that nine out of their 10 plans have been approved to date, and pointed to a series of infrastructure projects already in place, from replacing pipes to coming up with ways to intercept stormwater before it reaches the sewer system.

Officials broke ground this year on a $1.6 billion project to add underground storage tanks in Brooklyn’s Gowanus Canal that collect rainwater during heavy storms. Another $106 million was poured into building out a new sewer link in the Bronx.

Adi Talwar

A CSO/Wet Weather Discharge Point along the Bronx River near Tremont Avenue.Last week, DEP Commissioner Rohit T. Aggarwala announced that New York City would invest $3.5 billion in “sewered areas across all of the five boroughs” to better manage the intense rainfall “that climate change is bringing to the region and improve water quality in New York Harbor.”

And while DEP boasts that New York’s harbor is cleaner today than it has been in 150 years, environmentalists say the standards for measuring water quality fail to meet the stricter federal limits outlined by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

In 2017, nine environmental groups filed a lawsuit against the EPA to get the federal agency to force New York State to adopt a stricter threshold for what amount of fecal bacteria found in water should be considered safe for recreation.

“If you set the bar too low, with weak standards, you’re going to end up with weak plans for cleaning up sewage pollution,” said Larry Levine, a senior attorney with the Natural Resources Defense Council who is involved in moving the lawsuit forward. “And that’s really what we’ve seen happening. The state approves plans from the city that allows for billions of gallons of raw sewage to continue overflowing every year into the harbor.”

Last month, as part of an Earth Day announcement, the city pledged to “develop a strategy to end the discharge of untreated sewer overflows by 2060.”

“There has been progress over the years and we are seeing more of that. But the fact of the matter is there’s still a [long] way to go,” Levine added.

“So it’s really up to all of us to call on our city leaders to clean up that pollution and really protect a tremendous resource for New Yorkers.”

One thought on “Beach Season is Here. How Clean is the Water in NYC? ”

As outlined in this good article, there has been been huge progress to reduce sewage overflows in NYC. And it comes at great cost and is a slow process. Overall, I would say that the city and agencies are doing a good job on this front. These huge projects must be well-studied before spending billions on any projects.