While talent helps, students also need knowledge, expertise and polish to get into dozens of New York City public school arts programs that use auditions and portfolios to screen applicants. Although these schools have largely escaped the rancorous debate over selective admissions policies, they raise many of the same concerns about equity, class and race.

Nigel Campbell graduated from New York’s LaGuardia High School in 2004, launching him on a dance career. But during the Black Lives Matter protests, Campbell said, he and Chanel DaSilva, a fellow LaGuardia alumnus and his long-time friend and fellow dancer, “realized there were very few people of color in the space we occupy.”

In response, in 2015 they founded MOVE/NYC to bring greater diversity to “the dance profession and beyond.” And so on a recent April Saturday, about 25 teenagers met at the Mark Morris Dance Theater in Brooklyn to try to gain admission to programs designed to address the disparity Campbell and DeSilva saw.

Though most of its participants attend dance classes, MOVE is not a dance school, but a program to help promising young dancers and their families navigate the admission process for dance colleges—and New York City public high schools that require auditions, which can be equally competitive.

“You can be a very good dancer, but you need support in the actual process of applying to the school,” Campbell said. “Very few kids will get in solely based on raw talent.”

While talent helps, students also need knowledge, expertise and polish to get into dozens of New York City public school arts programs that use auditions and portfolios to screen applicants. Although these schools have largely escaped the rancorous debate over selective admissions policies, they raise many of the same concerns about equity, class and race that public schools screening applicants with test scores or grades do.

The city’s public schools offer specialized arts programs at all grade levels. Some are open to all, but 14 high schools screen almost all their students by audition or portfolio, and about 10 general schools offer one or more programs—dance at Fort Hamilton High School, for example, or art at Edward R. Murrow—that require auditions. A smattering of middle schools and at least two elementary schools screen students for the arts.

The Department of Education (DOE) has made efforts to remove biases in the audition process and to streamline it. Instead of auditioning in person for each individual program, as was the case before the pandemic, students apply virtually with videos and photos and can use the same material for all schools in the same field. But the bar remains high, and critics charge that auditions favor students who have had professional training, excellent arts instruction in their existing schools or professional coaching—resources out of reach for many children.

For example, eighth graders applying to some high school visual arts programs must send photographs of at least five original artworks including a self-portrait, still life and figure drawing, additional original work in any medium, and a full-page picture capturing “your wildest ideas of what a Fantastical Sandwich looks like.” They also must provide a video or short essay explaining three of the pieces.

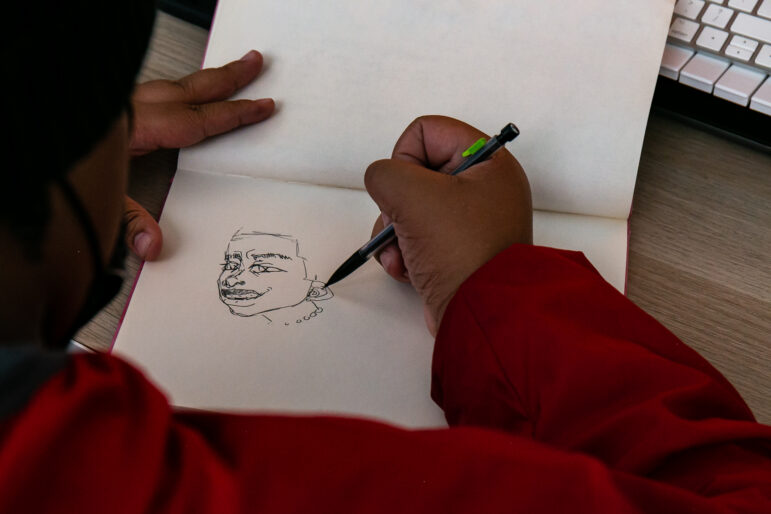

Adi Talwar

A student at the Harlem School of the Arts taking part in a “WEBTOON” workshop. The arts center offers programs to help participants prep for the city’s public arts schools.

Dance applicants submit two videos: a prescribed dance in one of four styles (ballet, jazz, etc.) and a one-minute solo demonstrating their “passion for dance.” Instrumental music aspirants also provide two videos, one a solo, the other a scale. The DOE website offers resources for those who don’t know what a scale is, though it’s questionable how many students get to this point without knowing that.

And the process can begin long before high school. Fifth graders who want to be in the singing program at Professional Performing Arts School must send a video of themselves performing 16 bars of a memorized song, while children seeking admission to second grade at the Special Music School must perform two or three “contrasting solo pieces” and two scales.

Calvin Walton, a lecturer in education at Georgia Southern University who has studied the impact of arts education on young Black men, says many elements can skew an audition process, including whether students have someone to help them prepare; what other factors, such as academics, the school might consider; and what qualifies as audition material.

Until the addition of August Wilson, for example students applying for many theater programs had to choose from monologues in “the canon,” all by white dramatists. (At present, New York City’s schools allow applicants to choose from more than 100 monologues or even select one on their own, and lets dancers choose from ballet, jazz, modern or West African dance for their audition solos.)

To help their children navigate this process, some families hire coaches for $125 an hour—in addition to having paid for private arts classes or individual lessons.

Alina Adams, a writer who runs the NYC School Secrets site, has written that it cost more to prepare her two sons to pass an audition for LaGuardia than to prepare them to pass the controversial Specialized High School Admissions Test used by Stuyvesant and seven other elite public schools.

“The level of skills a LaGuardia or a Frank Sinatra [High School] is looking for, that takes years,” she said. “I have clients, even people who have done five years of dance or drama and they don’t get in.” These schools, Adams said, “are not looking for raw talent.”

The situation is perhaps even more acute with middle school. “What is an expected level of professionalism for an 11-year-old kid?” said Miriam Nunberg, an education rights lawyer.

Few elementary and middle school students, particularly in poorer parts of the city, get the type of training most audition schools are looking for. While current figures are not available, a 2014 report by the city comptroller found more than 42 percent of all city public schools without any certified arts teachers were in the South Bronx or Central Brooklyn.

“In New York City public schools, arts are being cut all the time,” says Harlem School of the Arts President James Horton. “In a lot there are no arts programs, let alone arts programs that provide deep, quality instruction.”

Then there is the application process itself. While the changes made during the pandemic have improved things, they haven’t solved every problem, says Laura Zingmond, senior editor of Inside Schools.

“Some kids get more help than others,” Zingmond said. “Some schools are more energetic in helping kids prepare their portfolios, and some schools are better on staying on top of their eighth graders.”

Adi Talwar

Students at Harlem School of the Arts rehearsing for an upcoming production of Roald Dahl’s ‘Matilda the Musical.’

As with other admissions processes, the one for audition schools, “will always favor students who have adults who are engaged,” she added. “The majority of eighth graders don’t have the executive function to keep track of everything. The system is designed to have adult involvement.”

Syndi Nuesi of the Cypress Hills Local Development Corp.’s Middle School Student Success Center helps students at IS 171 and Highland Park Community School apply to high school. She thinks the audition process is better now than it used to be. Before the pandemic, she said, “students could have to go to three or four different schools to sing the same song,” making some students very nervous.

But trying out still poses obstacles for those who aren’t tech savvy or whose home may not have a quiet place to tape an audition video. “Some kids have to record it in the bathroom,” Nuesi said.

The two middle schools she works with have very limited art programs, and Nuesi worries about her own lack of artistic expertise. “It’s difficult to give constructive feedback if the people giving the feedback don’t have the background,” she said. For her students, “there’s not enough support in terms of what the audition should be like.”

Guidance counselors are supposed to help, but many are too swamped to provide the support some students need—or anything like what the child would get from a paid coach.

Despite such concerns, Nuesi said, all the students she helped apply to audition schools got in.

How much of a barrier the audition is is a complicated question, said one New York City music teacher who graduated from LaGuardia and whose son attends an audition school and who asked that her name not be used. A child needs to be exposed to the arts at home or school and have a family that will help them, she said, but she does not think families need to be wealthy.

“My feeling is that if a child has enough drive and support from the school and family, they will find a way to pass the audition and make it into one of these schools,” she told City Limits through an online forum.

What the numbers say

While disparities between the demographics of students at arts high school and those of the school system as a whole are not as sharp as they are for the specialized high schools, many top audition schools, like other selective public schools in New York, tend to have disproportionate percentages of white and Asian students. Their students are also more affluent, and far less likely to be English language learners

A number of arts schools, like their counterparts, skew heavily to one group or another. The student population at LaGuardia, for example, is 60 percent white and Asian and only 9 percent Black. At Frank Sinatra in Queens, about half of students are white or Asian. But at Wadleigh Secondary School for the Performing and Visual Arts, Theater Arts Production Company School, Fordham High School for the Arts, Celia Cruz Bronx High School of Music and Dr. Susan S. McKinney Secondary School of the Arts, more than 90 percent of students are Black and Latino. (DOE provides demographics only by school and not by program, so demographics for audition programs within other schools, such as dance at Fort Hamilton, are not available.)

The figures for income are particularly striking. More than 70 percent of all New York City public school students are classified as low income. At Professional Performing Arts School, LaGuardia and Special Music School, though, less than a third of students qualified for free or reduced-price lunch. And while about 14 percent of city school students are English Language Learners, many arts schools, including LaGuardia, Professional Performing Arts, Art and Design High School, and Brooklyn High School of the Arts have virtually none.

The schools are more representative in terms of students with special needs, owing to a program that requires schools to designate a certain percentage of seats for students with disabilities. But because it is a “specialized high school” subject to state, not city, law, LaGuardia is exempt from this requirement and only 4 percent of its students—in a system where 21 percent of students have special needs—fall into this category.

Before the pandemic upended the admissions process, news sites The Markup and The City compared the number of city high school applicants and acceptances by race. At many audition schools, Black students represented a far larger share of the applicants than of the students offered places. For white and Asian students, the situation was often reversed.

For example, at Professional Performing Arts, 28 percent of the applicants in 2020 were Black and 35 percent were Latino. For those accepted, the numbers were 12 and 22 percent respectively, while white students were 20 percent of applicants and 41 percent of those who snagged admissions offers. Frank Sinatra had similar numbers, with Black students accounting for 17 percent of applicants and Latinos for 35 percent, while among accepted students the percentages were 7 and 21 percent for those demographics respectively. White students were far more likely to win admission at the Queens school: They accounted for 24 percent of applicants, but 39 percent of those accepted.

All the audition schools have more girls than boys, according to Joyce Szuflita, who runs NYC School Help, which assists families looking for schools, raising an interesting question, she says: “Do boys have an advantage in [applying to] arts schools? If you’re building a chorus or a play, you need male voices.” Similarly, students playing an instrument that few other kids do but that’s needed for an orchestra—a flute or a trombone say—may have an edge over a violinist.

Raising the barriers?

The small theater vibrates with energy. Children dance and jump as a boy standing on an elevated platform belts out, “We are revolting children living in revolting times.” The chorus promises, “We will be a screaming horde,” while a girl demonstrates how to “take out your hockey stick and use it as a sword.”

When they finish, coaches, some of whom performed together in “The Lion King” on Broadway, tell the cast members to do it again. And they do—eagerly.

The students have spent hours preparing for Harlem School of the Arts’ production of “Matilda.” Founded by opera singer Dorothy Maynor in 1964, the school offers activities, classes and individual instruction in a range of arts to hundreds of students a week. While only a small percentage of children as young as 2 who come to the school will want to attend an arts high school or college, for those who do, Harlem Arts offers HSA Prep, a free program that helps students get ready for admissions auditions.

For someone to succeed in the arts, says director James Horton, “technique is just as critical as raw talent. Raw talent, and technique, and passion, are what make you great.” But, he said, people also need access and opportunity, so Prep is aimed at making sure “opportunity is not the barrier.”

Harlem School of the Arts also is one of several arts organizations that collaborates with the DOE to offer free two-week Middle School Arts Audition Boot Camps every summer. The goal, says the camps’ website, “is to provide equity and access” for students from low-income schools who want to apply to a screened high school arts program.

Studio in a School, another nonprofit, runs the programs in visual arts at a school many of the students will apply to: LaGuardia. More than 100 are expected to attend this summer. They will leave with two or three finished pieces for their portfolios and return for two sessions in the fall to add more.

“We give students a safe place to take chances with their work and to think of themselves as artists and as part of a community,” said senior director Julie Applebaum.

President Alison Scott-Williams says the boot camp has a high success rate at getting students through that process, not only by providing them with art instruction but by making it clear what they will have to do. “50 percent of being able to be successful in a competitive process is to know what’s going to be expected of you,” she said.

But some think these programs, whatever their strength, can only do so much. Like the academic screening process, the arts auditions raise the question of whether public schools should select students and the challenge—or impossibility—of creating a fair admissions process in a city rife with inequities.

Since its founding in 2002, the Oakland School of the Arts, a charter school in California, had required auditions to select students who understood what going to an arts-focused school would entail and who were committed to that. But as Oakland became gentrified, the student body became increasingly white. “All of a sudden you had kids who had had dance training or music training for four years,” director Mike Oz said.

Even though the school’s “Step It Up” program helped low-income students of color get in, the school district worried the auditions “were creating exclusivity.” At its behest, the arts school began phasing out auditions in 2019 and now instead selects applicants by lottery, with preference going to certain students, such as those who have siblings at the school or went to a neighborhood elementary school. Oz says it’s too early to determine if the change has affected the school’s quality and programs.

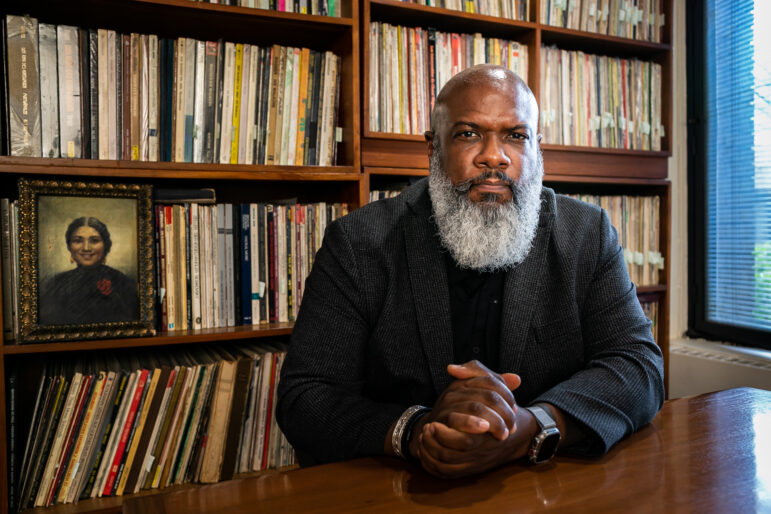

Adi Talwar

“Technique is just as critical as raw talent,” said James C. Horton, president of the Harlem School of the Arts. But, he added, people also need access and opportunity, so HSA’s Prep program is aimed at making sure “opportunity is not the barrier.”Closer to home, New Voices School of Academic and Creative Arts required auditions and was one of the most sought-after middle schools in Brooklyn’s District 15 when the district launched an effort to end segregation in its middle schools. “We were all very clear that test scores and grades and attendance were very discriminatory,” said Nunberg, who served on the working group which developed the integration plans. But the group was unsure what to do about auditions.

The tipping point came when a teacher told the group students were coming to her at the beginning of fifth grade to ask for piano lessons so they could audition for New Voices a few months later. By then it was, of course, far too late.

New Voices no longer requires auditions, and its demographics have changed. White students, who accounted for 53 percent of students in 2018-2019, the last year with auditions in place, made up 38 percent of the student body in 2021-22, while the number of Latino and Asian students increased. Most strikingly, the school’s percentage of low-income students rose from 29 percent to 54 percent.

Not far away, MS 936 in Sunset Park decided to go the other way—but not without controversy. After the city stopped selective admissions at middle schools during the pandemic, MS 936 announced it would begin auditions for the class entering in 2022, to the dismay of many in the community who worried immigrant and low-income children who lived nearby would be at a disadvantage. According to the Brooklyn Paper, after the school began using auditions, the number of low-income children, English language learners and students from nearby elementary schools declined.

With arts a major part of life in New York, most education advocates agree schools should reflect that and provide support and training to students who see arts as a potential lifelong passion or career. The disagreement is whether there should be special programs for that and, if there are, how students should be selected for them.

“In a system of about a million kids, there are going to be child prodigies and the schools should serve them,” Zingmond said. “There is value in having audition schools at the high school level as long as there’s fair play.”

Nunberg agrees. “In New York City, with so many artists, should the public schools be in the business of training artists? Yes, I think they should,” she said. But whether to have auditions or not is “a really, really complicated question.”

“If you’re having this very high standard of technical training to enter that school and you’re not providing that training, it’s favoring people who can afford private lessons,” she continued. “How do you remove the influence of something that costs money or takes adult involvement?”

Oz says that for auditions to work, the panel evaluating them has to be properly trained and schools must offer programs to help students apply. In the end, the process has “to emphasize commitment over preparation and that’s not always easy to do,” he said.

Others argue that any type of screening in arts education is a barrier to something all young people should have standard access to. In his research, Walton has found that exposure to arts can offer surprising academic and other benefits. He recalled a high school student studying dance who said his work on choreography had improved his ability to write English essays.

“We need to really normalize arts education,” Walton said.

Editor’s note: The author of this piece is the parent of a LaGuardia High School alum.

One thought on “At New York’s Other Selective Public Schools: Auditions for 9th Grade ”

Re: 9th Grade Auditions. My daughter, a bright student, did not meet the academic requirements for LaGuardia but aced auditions at arts high schools. I never spent $ on arts training. She learned music and dance for free at ps183, Wagner Middle School, Talent Unlimited, MS Audition Boot Camp, NYC All-City Concert Band, Honors Festival, Summer Arts Institute and most importantly National Dance Institute (NDI). She spent 4 years on NDI’s SWAT then Celebration teams and received the most extraordinary dance, music & leadership training under and fulfilling Jacques d’Amboise’s vision that arts training is critical to humanity and should be free! She is a far better student and leader because of the arts. There are many opportunities for students but they are not easily found. My daughter received her NDI scholarship on her own and pursued music independently. It was only in high school that I realized its value and started researching programs. NYC DOE, community programs and the Media should build more awareness especially in the schools for children. We don’t have great sports programs so for active children that may be younger for their grades, may have underdeveloped executive function or just don’t fit exactly in the box of great test takers or passionate readers, the arts may inspire them to become lifelong learners if they find this light.