“In the 2020 Census, the New York City metro area was found to be running just behind Milwaukee and Detroit as the third most segregated region of the country according to Black-white segregation data. This is not by accident.”

HOLC

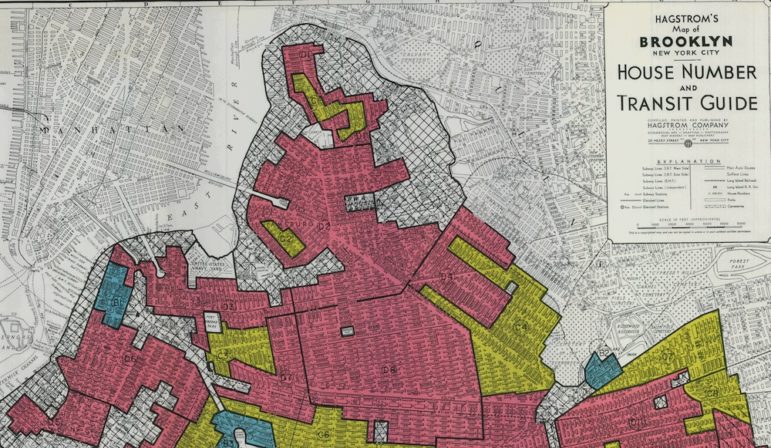

A redlining map of Brooklyn.Racist policies of the past designed the segregated, unequal landscape we live with today, and exclusionary zoning perpetuates it.

In the 2020 Census, the New York City metro area was found to be running just behind Milwaukee and Detroit as the third most segregated region of the country according to Black-white segregation data. This is not by accident. Federal, state and local policy intentionally created a landscape of exclusionary, homogenous areas alongside more diverse and often more disinvested cities, towns and neighborhoods.

There is a reason so many do not want to tell this inconvenient history. Far from simply independent, locally-determined hamlets, in reality these exclusive places have been just as much creatures of large-scale policy as any redlined neighborhood.

In our Undesign the Redline exhibit, we examine the history of neighborhoods that have been systematically segregated and disinvested for decades. Neighborhoods were coded “red” as hazardous for investment on 1930s federal redlining maps with starkly blatant language such as, “detrimental influences: Negro infiltration.”

At the same time, the Federal Housing Administration created an underwriting manual that would go far beyond the maps. They instructed mortgage-issuing banks to look out for “whether incompatible racial and social groups are present, for the purpose of making a prediction regarding the probability of the location being invaded by such groups. If a neighborhood is to retain stability, it is necessary that properties shall continue to be occupied by the same social and racial classes.”

The real estate industry itself was even more direct in their language. An example from a real estate textbook predates federal redlining policy, and echos the same sentiments: “The colored people certainly have the right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness, but they must recognize the economic disturbance their presence in a white neighborhood causes, and forgo their desire to split off from the established district where the rest of their race lives.”

These damning quotes point to the other side of redlining: “green” areas, those coded as desirable and a good investment. What made an area green was not only that white and usually wealthy people were living there, but that there were restrictions on “hazardous infiltration,” meaning there was a racial covenant, or it was in the deeds of the homes that you couldn’t sell to a Black or Latino family, among others.

These restrictions are what the FHA was referring to when they mention removing the “probability” of “being invaded.” Many suburbs, villages and neighborhoods in New York were created because of this policy. The system this established was clear: exclusion itself gave these neighborhoods their value, and exclusion alone could preserve it.

By the 1970s, after the implementation of the 1968 Fair Housing Act made this explicit racism in housing illegal, restrictions on zoning density, lot size, height requirements and more increased dramatically in suburban areas. Fast forward to 2023, and these policies have in effect preserved many towns and neighborhoods exclusively for wealthier, often whiter residents. Many of our fellow New Yorkers genuinely profess support for the cause of racial justice and equality under the law but fail either to recognize or acknowledge how those same values are stymied in their own backyard.

Listening to some disheartening arguments being made against finally ending exclusionary practices today, one would be forgiven for wondering if some have a more cynical view: maybe everyone has the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, but not here.

New York is in desperate need of more housing, and affordable housing especially. This is reason enough to guarantee that every city, town, and neighborhood is a place where a diversity of people with a range of incomes can live and thrive together. We can design beautiful, vibrant, walkable communities, especially centered around transit, that will actually improve the quality of life for everyone nearby.

That vision doesn’t sound so bad? But ending the long history of residential exclusion is also a goal in and of itself. There is a reason that voluntary incentive programs have failed and fear mongering has succeeded when it comes to producing new and affordable housing in historically exclusionary towns and neighborhoods. That’s why any Housing Compact plan being considered in Albany needs to ensure the end of exclusionary practices that prevent new and affordable housing, period.

Working families should be able to afford a home in New York, and there will be more to do to ensure that right. Affirmatively furthering fair housing will also take continued policy changes. But we have the opportunity to advance both goals here and now. When policy makers see our redlining exhibit, many have asked what policies and practices today will our children and grandchildren look back on and regret for perpetuating injustice? Exclusionary zoning is one of those policies.

Braden Crooks is the co-founder of Designing the We.

3 thoughts on “Opinion: How Exclusionary Zoning Perpetuates Segregation in New York”

Again great opinion topic, Yes nyc definitely have a affordable housing segregation issue, if you have market rate or high middle income, u get to live in better off to do neighborhoods , if your a low income of any kind, you can only live in undesirable areas, atlantic yards/pacific park is one example, down town brooklyn new housing is another

Are you that stupid to think that any modern bank from the 1960s onward paid any attention to the so-called ‘redlining’ maps drawn up in the 1930s, or for an underwriting manual written in 1938?

The redlining maps were obsolete by 1950 and in many cases areas were redlined for nothing to do with race. Many middle-class areas of Staten Island like parts of New Dorp and Oakwood were redlined on those 1930s maps becasue of the poor drainage and lack of sewers at the time. By the 1960s those areas had sewers or sewers were being planned. No bank in the 1960s on Staten Island was issuing mortgages based on 30 year old maps.

Where’s the exhibit?