“If Mayor Adams wants to make a positive impact on the city and take his ‘working people’s agenda’ beyond rhetoric, he needs to embrace a trifecta of change that establishes a culture in City Hall centered on the needs of everyday New Yorkers. This means establishing a re-imagined social contract, ending the austerity mindset that has dominated the city’s budget and policymaking, and managing for consequential change.”

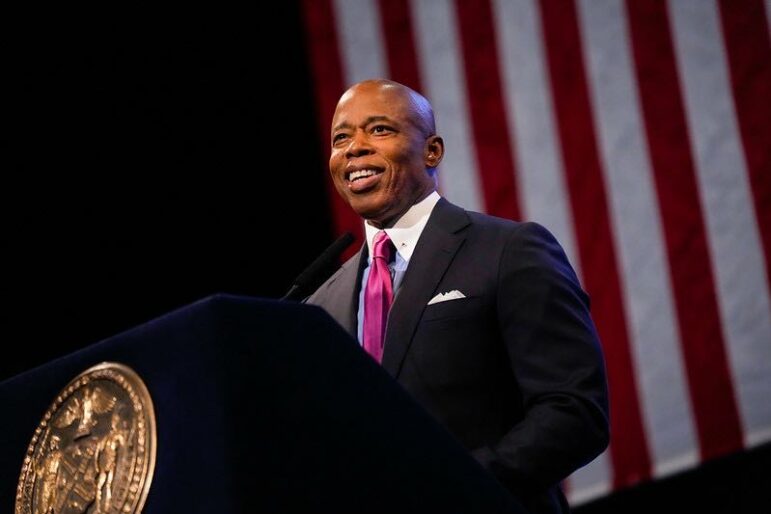

A few days before delivering his recent State of the City Speech, Mayor Eric Adams announced he would be starting an email newsletter that City Hall will send to New Yorkers highlighting the achievements of his administration, which he felt were being neglected or misrepresented by much of the city’s press. But there seems to be something else at the heart of that frustration: perhaps it’s the press challenging his governing philosophy. Or perhaps it is the press assessing his achievements thus far, and it not squaring with his “get stuff done” rhetoric.

If Mayor Adams wants to make a positive impact on the city and take his “working people’s agenda” beyond rhetoric, he needs to embrace a trifecta of change that establishes a culture in City Hall centered on the needs of everyday New Yorkers. This means establishing a re-imagined social contract, ending the austerity mindset that has dominated the city’s budget and policymaking, and managing for consequential change.

Culture change: a re-imagined social contract

Getting the city’s social contract right is an essential first step in realizing systemic and structural change. This means moving to a culture that promotes burden sharing, decency, and generosity for the collective good. It means a new moral compass that doesn’t just point to the elite few. Choices made today must be more than the acceptance of half measures resulting in mediocre outcomes. If we don’t make this change, choices will be small, and not lasting. Worse, it will send a clear message that city government is not there for everyday residents. We need a governing culture that works for all our communities: providing good, truly affordable housing, as well as decent transit, thriving schools, parks, playgrounds, libraries, and stores.

In this pivotal moment in the city’s history, the mayor has so far left the city more dependent on elite institutions and individuals. They sit comfortably around the mayor’s decision-making table, ever protective of their wealth at the expense of the city’s needs. While he has called for cutting subsidies to the city’s libraries by $33 million over the next year and a half, he has asked nothing from the millionaire sports venue owners, who pay nothing in property taxes. Clearly the choice to cut libraries is antithetical to his commitment to the working class.

And for a second year in a row, the mayor fell short on a campaign promise to give the Park’s Department 1 percent of the city’s budget to support this vital public amenity. In fact, he has proposed, in his preliminary budget, a cut of $46 million to Parks. These are classic examples of poor choices, hurting the very constituency he claims to support. As a city, we cannot continue to accept small ambitions for government obligations.

The austerity trap

New York City is facing significant fiscal challenges in the years ahead. As someone who spent 14 years in city government, including four years as director of operations under Mayor David Dinkins, during which time the city was in a deep recession, I learned a fair amount about community needs and services.

During that time, rather than cut, policy choices and decisions were made to improve neighborhood services and access, including extending library services to six days a week, the first time since 1947; selected health clinics were extended to evening hours and weekends; after-school hours were extended in selected schools (The Beacon School initiative); and recreation centers and indoor swimming pool hours were extended to nights and weekends.

But more often, in good times as well as bad, austerity has dominated budget and policy choices. A focus on austerity constrains governing options. Embracing an austerity philosophy of governing is a cautionary tale for the city: poor choices lead to poor policies lead to poor outcomes. An austerity agenda has left the city’s treasury starving many vital public services and essential government functions, frozen in old dogmas that undergird decision-making.

It also allows institutions and individuals to skirt laws and regulations, confident that government only offers weak guardrails. Let’s understand that laws and regulations are not “suggestions” for behaviors and actions by the wealthy few. When institutions and individuals can’t or won’t regulate themselves, is when government must step in to regulate and enforce predatory behavior. Parsing wrongdoing is an on-going task. Nothing less than aggressive litigation and prosecution of misconduct is needed.

While the mayor has focused on street crime, he is silent on cracking down on white collar crimes that pervade our city. The mayor has yet to set boundaries and guardrails on predatory practices. Lax enforcement, beyond street crime, has plagued the city for decades. For example, the mayor has shown little interest in cracking down on recalcitrant landlords who skirt property violations.

He has failed to crack down on landlords who fail to maintain their buildings, especially in underserved neighborhoods. How many stories will we read each winter of tenants without heat or hot water, with few consequences felt by landlords for ignoring building violations? The share of emergency housing code violations corrected by owners has declined annually since 2019, according to data in the Mayor’s Management Report. Yet the NYPD has stepped up enforcement of street vendors’ violations. A low bar example of “taking action.”

Management: getting from creed to deed

In the 1960s we said, “there is a growing chasm between the creed and the deed.” A change in City Hall culture and a move away from decision-making subsumed by austerity politics needs to be accompanied by a management approach that includes disparate voices and communities. So far, we have seen the same entrenched interests dominating the decision-making table.

Hindering a move from creed, whether campaign promise or State of the City declaration, to deed, is the thousands of city jobs the mayor has left vacant. As former City Council Speaker Melissa Mark-Viverito told the New York Times, “I’m a progressive, and my priorities are going to be very different from the mayor…But I’m also concerned about the management side and whether the city is providing the basic services that New Yorkers rely on.”

Her concern is well founded. A recent report by City Limits found that the Human Resources Administration is struggling to process food stamp applications in a timely fashion. According to the September 2022 Mayor’s Management Report, processing time dropped to 60 percent within 30 days during Fiscal Year 2022 compared to 92 percent in FY2021. In another area, the city, by law, was supposed to add 30 miles of bike lanes and 20 miles of dedicated bus lanes last year, but the Department of Transportation, wracked by job vacancies, fell well short.

Although the mayor may have thought eliminating vacant jobs was an easy way to achieve sizeable savings in his most recent budget plan, appeasing the austerity hawks while avoiding layoffs and the wrath of municipal unions, it was short-sighted and wrong. Brad Lander, the City’s Comptroller, noted “that the budget was not ambitious or focused,” adding, “This budget meanders with little direction.”

This budgetary meandering and failure to meet service needs reflects one management shortcoming. Another is a seeming lack of city and state collaboration to achieve consequential changes. Some issues require enormous skills and competency and often they need multiple government organizations and stakeholders to step in and step up to bring about structural changes to achieve consequential and lasting outcomes.

Here are three examples that also would buttress Adams’ working people’s agenda:

- Tackling wage theft: These crimes that go unpunished account for $1 billion stolen from workers’ salaries annually. In recent years, part-time and temporary work have become an increasingly prevalent part of the city’s employment landscape. And for years, minimum wage requirements have been ignored, eroding employees’ wages. And even as minimum wages have increased, some employers have chosen to pay their employees less, or undermine overtime protection by misclassifying workers’ job titles. The working poor cannot subsist on low wages and uncertain work schedules. And these conditions wreak havoc on families’ lives. This is a story played out daily in too many workplaces. Elected officials at both the city and state have known about this abuse for decades and done little about it. Changes in state labor laws and enforcement capacities at both levels of government are required in order to ensure workers are getting fair wages and benefits. This is not a quick fix and will require years of sustained work.

- Changes to the city’s property taxes: Changes to tax laws related to sports venues, “non-profit” universities, hospitals and museums would maximize this essential revenue stream. This will require collaboration with Albany, but once achieved, would generate $1 billion in tax revenues annually.

- Creating a municipal bank: This will require collaboration with the state and the city’s comptroller to create this new banking option, which would allow the city the ability to divest its relationships with the Wall Street banks and redirect those resources to neighborhood banking institutions, credit unions, land trusts, and cooperatives. A public bank would provide credit to community businesses and related community needs. The mayor campaigned on this issue: to date, he is silent on this campaign promise. In recent years, The New Economy Project, along with other advocacy groups, have pressed Albany for this needed legislation.

Managing the city also means managing labor relations. The municipal unions are a major entrenched interest, one that absorbs more than half of the city’s $100 billion budget. With the contracts for many of the unions expired or soon to end, the cost is sure to rise. Will paying for raises come at the cost of other city needs or will the mayor seek productivity measures and claw back costly work requirements to offset wage and benefit costs?

The mayor could seek an end to the wasteful unlimited sick leave policy for uniformed services, police, firefighters and correction officers that has been in place since the 1970s. He could seek a consequential productivity gain by increasing the work week from 35 hours to 37.5 hours, the same as the New York State work week. He could also seek to end overtime when calculating pensions. And he could seek to reflect post-pandemic realities by revamping the work week to allow for a four-day schedule. A four-day work week, where appropriate, can reflect a restructuring of how work is delivered and address some of the challenges related to worker hiring and retention that confront the city today.

Beyond the power of wealth

The business of governing is never ending. What’s enumerated here, is not exhaustive, merely examples of the work ahead of us.

In his first State of the City address the mayor said, “FDR understood that the people needed an honest reckoning of the problems and bold plans to solve them.” And he added, “That is what I intend to deliver for my fellow New Yorkers.” From the choices he has made, we can measure his commitment to lead.

In his second State of the City, Adams said in his opening remarks, “Without a strong working class, this city cannot survive. That’s why I’ve outlined how we plan to build a city for working people.” And in his closing remarks, he said, “City government must work to improve the public good, support an economy that works for all, and care for the working people who make it possible.” He closed by saying, “It is the working class that has lifted up this city, built it brick by brick on the bedrock of a free and democratic nation. And going forward, we will sustain the workers who make this city possible.”

Again, nice words. But what he fails to invoke is an understanding of a re-imagined social contract: show us, by the choices you make, that you really believe in the power of government to be more than the power of wealth. Or in the words of RFK, “The problem of power…is how to get men of power to live for the public rather than off the public.”

For over 40 years, Harvey Robins has worked in various positions in city government, non-profits, and foundations, including the NYC Human Resources Administration, the Board of Education, the Mayor’s Office of Operations, the Children’s Aid Society, and the Edna McConnell Clark Foundation.

2 thoughts on “Opinion: To Deliver for New York’s Working Families, Mayor Adams Needs a Trifecta of Change”

on the opinion of delivering to the working families, you are 100% correct, and also for mayor who says do we need windows in apartments, to fix the affordable housing crisis, and want to keep new apartment units shoe box size, is going to run this city down the drain by hurting the working poor,modrate,senior,retired, people, then again maybe thats what he wants, NYC FOR WEALTHY, some of these elected officials are in bed with these big real estate developers and can care less about anything else

What about forcing retirees to pay $200 a month to keep their Medicare benefits. I worked 40 years to attain this benefit what authority does the mayor have to steal my cost of living increase