“We learned decades ago that institutionalizing people, or locking them away in state mental hospitals, was not the solution. This practice demonized people with mental health challenges, disappearing them, and led to facilities that were dirty, dangerous, and inhumane.”

Ed Reed/Mayoral Photography Office.

Mayor Eric Adams announcing the new directive at a press conference Tuesday.Mayor Eric Adams announced last week that he plans to solve New York City’s homeless crisis by involuntarily hospitalizing anyone observed to be mentally ill, regardless of whether or not they are deemed a threat to themselves or others. If this is the city’s plan to address our decades-long mental health and homelessness crises, we wonder, when will we stop forcibly locking people away to create the illusion of public safety and instead address the underlying causes of this problem?

As advocates—and importantly, as someone with lived experience—we know that everyone deserves a dignified place to stay, regardless of immigration status, criminal legal system involvement, and medical and mental health needs. We have a right to shelter law, but that shelter has never been dignified, stabilizing, nor supportive. People choose to stay in the street and in the subways because the shelter system is not desirable, and it is not dignified.

We learned decades ago that institutionalizing people, or locking them away in state mental hospitals, was not the solution. This practice demonized people with mental health challenges, disappearing them, and led to facilities that were dirty, dangerous, and inhumane.

As co-author, Raul speaks from experience. He spent significant time in the New York City shelter system and felt humiliated, demoralized, and dehumanized. Overcrowded, dirty, congregate spaces, unsafe conditions and a lack of hands-on, knowledgeable support staff did not create stability. The shelter system is not desirable, and it is not dignified. Dignified shelter means private space, including a bathroom, and true, goal-oriented support that responds to people’s identified needs and guides them on a path to permanent housing.

But Raul was lucky to have an advocate who pushed to get a reasonable accommodation entitling him to a private room within the Department of Homeless Services (DHS) system. That private room gave Raul a little bit of himself back. He had his own fridge and bathroom, things that might seem small but are significant because they offer a critical sense of autonomy and dignity.

So much of achieving stability is about feeling capable, respected, and truly supported. Residents of the re-entry hotels have been echoing this since the program began—that a program like this, with support staff who do not judge and truly want to help, coupled with a physical environment that feels safe and dignified, is enough to change someone’s life.

But the current state of our shelters is a barrier to people’s release from jail and detention settings every day. When someone is known to the court as a person struggling with mental health or substance use challenges, unfortunately, judges and prosecutors know the state of the shelter system and often do not feel comfortable releasing vulnerable people there. This means that people with mental health and substance use challenges spend more time on Rikers Island solely because they cannot access housing.

Non-citizens are also disproportionally left behind by the shelter system. Undocumented individuals are threatened with losing their shelter bed if they don’t apply for services that they don’t qualify for such as section 8 housing. The over-policing of our current shelter system also puts non-citizens at a higher risk of arrest which could result in their deportation. They are left without supportive services, worrying they will lose the roof over their head at any moment or worse, be forced to leave the country.

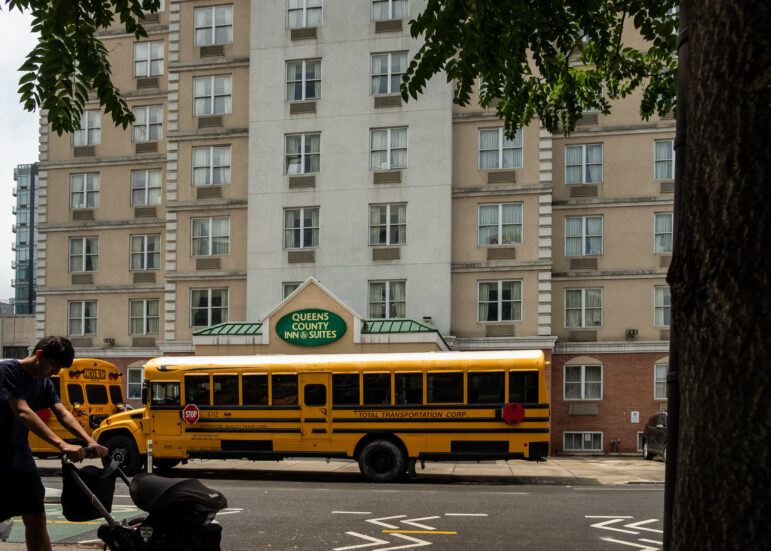

The city responded to the COVID-19 crisis, and the shelter system’s involvement in spreading COVID, by utilizing hotel rooms to house people, part of an emergency re-entry housing program preventing those coming out of jail and prison from going into congregate shelter spaces.

On top of transportation directly to a private hotel room, people reentering the community from custody were also supported by case managers and residential staff and had the option of onsite medical and mental health services provided by Housing Works. For the first time for so many cycling in and out of jails, hospitals, and shelters, they had a safe, private space where they knew their belongings wouldn’t be stolen while they slept.

We agree that the city must respond to the unmet needs of so many unhoused New Yorkers struggling with mental health challenges. A response to this crisis is long overdue, but the mayor’s response makes clear that he is not concerned with the wishes or overall well-being of all New Yorkers and is not familiar with the experience of navigating the hospital and shelter systems. The mayor’s plan does not respond to the myriad of root issues facing this population and as such does not truly address public safety at all. Like jailing people, forcing them into hospitals that will discharge them hours or, at a maximum, days later with the same needs is not the solution.

The emergency reentry hotel program has shown us what is possible if the city invests in responsive, immediate, and dignified shelter for the most vulnerable New Yorkers. We know our city is capable of providing dignified, supportive shelter to all, and Mayor Adams can show his leadership by investing in what people actually need and want.

Raul Ubiles is a Bronx resident. Julia Solomons is a Senior Policy Social Worker in the Criminal Defense Practice of The Bronx Defenders. Rosa Jaffe-Gaffner is Director of Social Work in the Civil Action Practice of The Bronx Defenders.