With pieces dating back to the early 20th century, the city’s public schools are home to almost 2,000 works encompassing realistic murals depicting the city’s history, giant pieces on exterior walls, playground installations that teach children about sound, fanciful fences and wall installations with nooks and crannies for students to explore. Faith Ringgold, Keith Haring, Romare Bearden and Carrie Mae Weems are among the many prominent artists represented.

Adi Talwar

Art Spiegelman’s 17 panel hand-painted stained glass installation titled, “It Was Today, Only Yesterday… (A Window of Time)” at the High School of Art and Design in Manhattan.The cartoony figure of an artist at work watches over the activity below. Inspiration, perspiration and craft nurture his brain, but a grizzled figure representing self doubt will not go away.

The colorful glass installation could grace a museum, performance venue or gallery. Instead it’s in a New York City public high school, looking out on the cafeteria at the High School for Art and Design in midtown Manhattan. Created by school alumnus and celebrated cartoonist Art Spiegelman, “It Was Today Only Yesterday…” features scenes of an artist at work, along with panels celebrating the school’s past, present and future graduates—and a dash of autobiography.

“It represents all our futures here. It gives us inspiration when we see it,” said senior Eva Bell.

Spiegelman’s 2012 installation is among hundreds of artworks in a little known collection: the School Construction Authority’s (SCA) Public Art for Public Schools (PAPS). With pieces dating back to the early 20th century, it includes almost 2,000 works in all five boroughs and encompasses realistic murals depicting the city’s history, giant pieces on exterior walls, playground installations that teach children about sound, fanciful fences and wall installations with nooks and crannies for students to explore. Faith Ringgold, Keith Haring, Romare Bearden and Carrie Mae Weems are among the many prominent artists represented.

Since 1982, under the Department of Cultural Affairs Percent for Art program, 1 percent of the budget for “eligible city-funded construction projects” in New York City, including new schools or school additions, has been set aside for public artworks. In 1989, the city established Public Arts for Public Schools within the School Construction Authority to commission and install the art outside school buildings and in lobbies, hallways and classrooms.

Having art “shows that schools are really important and important as community centers,” said Michele Cohen, the founding director of Public Arts for Public Schools. “It communicates that this is a special place and you [students] are important.”

“Children who may never have an opportunity to be in a museum or see a professional artwork, our aim is to provide that for them in their daily lives,” says Tania Duvergne, the current director. “It’s an educational opportunity that is different from books and exams. … It bridges divides.”

The right art in the right place

Creating public art for any space presents a series of challenges, and the requirements for works intended to last for a century in a public school in a diverse and ever-changing city are particularly daunting. For one, it must be meaningful today—and remain that way for decades.

“You have to think about what this artwork is going to look like 30, 50 or 100 years from now in terms of its content and materials. We want each student to feel it belongs to them and they’re referenced in that artwork,” said Kendal Henry, assistant commissioner of public art at the Department of Cultural Affairs.

“A lot of the work is connected back to the community and to the site,” said Jennifer McGregor, the first director of Percent for Art. At the same time, it can’t be too specific because the art will be there for 100 years more or less—and in that time communities will change.

It should “fit into the architecture of the building so it looks like it belongs there, not posted on the wall,” said Cohen. And it has to be durable. “Any time you put art in public spaces you have to maintain it and schools are a challenging environment,” said Cohen. “You want to put things where they’re somewhat out of reach.”

Although students can walk right up to Spiegelman’s work and even look through it, it meets many of the other criteria.

The artist said he wanted to “offer something that would be fun but also the more you stay with it the more it unpacks.” After months, or even years at the school, a student could likely still find something new in the 17 panels. They can look through “eyes” in the installation to see their friends below, pick out depictions of famous alumni, such as Calvin Klein and Harry Fierstein, look for Spiegelman’s autobiographical reference or chuckle at the visions of the graduates of the future.

Above: works by Spiegelman and Abraham Joel Tobias at the High School for Art and Design in midtown Manhattan (Photos by Adi Talwar)

Spiegelman chose hand-painted etched glass, partly because he wanted students to be able to read the work as they would a comic: “Stained glass windows were comics before there was newsprint.” And he wanted it to go above the cafeteria because “it was the social nexus of the school” when he attended, “and I think still is.”

Overall, he said, the work shows “my experience at the school forwarded to now. They’re lucky to be there.” Even though many students do not know Spiegelman created the installation, they said they get his message. “It is very encouraging. It gives us inspiration when we see it,” senior Anneliese Wang said.

Spiegelman said as far as he can tell his installation “seems to be integrated into the heart of the school.”

That is one of the city’s criteria as well. Often—though not in the case of Art and Design—the artwork is “the first thing people see. The art becomes the face of the school,” Henry said.

There is no shortage of artists in New York. Working on art for a public school, McGregor, lets them try something new and may serve as an entree for doing other public art pieces. “One of the things that excited artists about being in a school building is that we’ve all been students,” she said.

The SCA maintains a registry of artists interested in doing school projects. At the very beginning of a school’s planning and construction, a committee selects 30 or 40 artists from that registry who might be a good fit with that particular school.

“PAPS is on board at the very, very beginning,” Duvergne said. The architect, engineer and artists all must work together to ensure, for example, that the art is appropriate to the size and shape for the space and that no structural elements, even electrical outlets, will get in the way. The process can take five years from start to finish.

Eventually the committee—with representatives from SCA, the Department of Cultural Affairs and the Department of Education, as well as two people from the art world, including one of whom has gone through this process before—selects three or four artists, who are then invited to submit a proposal.

The school community “has a huge role in our process and what the feel of the school needs to be and how that’s interpreted through the art,” said Henry. “The school is super involved and we accommodate them as much as we can without sacrificing the integrity of the art.”

Any project selected, Duvergne said, “needs to be inclusive of all communities.”

“It should make every child feel that they’re a part of it, now and in 50, 100 years,” she added.

The process seems to have avoided controversy—for the most part. In the 1960s, students at what was then Evander Childs High School in The Bronx objected to the depiction of Black people in James Michael Newell’s 1938 murals “The Evolution of Western Civilization” and some of the mural was vandalized. The work was allowed to remain in the campus library but is now accompanied by a student mural in the hallway, and material that puts Newell’s work in context.

There can be other glitches. A second installation at Art and Design High School—a stainless steel sculpture by Lawrence Weiner embedded in the floor—is often covered with mats, students said. The piece gets slick in the rain and the school worries about people slipping.

One artwork, many perspectives

Unlike a gallery or museum people may visit once or twice, students are in their school several hours every day for as many as nine years. In preparing their proposals, artists must consider that, Henry said, and create work that “can be experienced at many different levels, literally and figuratively.

Above: Penelope Umbrico’s “Cabinet 1526-2013” at PS/IS 48 on Staten Island (Photos by Adi Talwar)

Even after nine years at the PS/IS 48 on Staten Island, few children will have absorbed all of Penelope Umbrico’s “Cabinet 1526-2013.” Spanning a long hallway, the work includes 6,000 images of plants, animals and astronomical bodies created between 1526 and the early 20th century, held together by a metal lattice that Umbrico said, “acts like a window box for each image.”

“I wanted to give them a visual encyclopedia of the natural world before the web,” she said.

Because the installation is almost the full height of the hall with pictures at every level, children will see it differently from year to year as their own eye-level changes. “As you grow up, you will be experiencing new imagery just by the fact that you’re growing,” said Henry.

The sheer volume of the images plays a key role too. “I wanted it to be a more interactive piece with the students, something they could not only look at but actually use,” Umbrico said. “If I was them there would be my favorite image and I would look at it every time I walked by.”

For at least some that seems to be the case. Students bounce up against “Cabinet,” with some looking at it, some pointing out details to their friends and some ignoring it.

Four glass boxes next to “Cabinet” pay homage to the dioramas at the American Museum of Natural History. Umbrico worked with kindergarteners in the school’s first class to create scenes in those boxes using toy animals and other knick knacks. In one, lions cavort on a rock while a big china bunny looks on.

“When they came out and put their pieces in, it was like Christmas,” Duvergne said.

This month those kindergartners are graduating from PS/IS 48, but their dioramas will live on.

“Cabinet” is not the only artwork that invites student involvement. Under the Sites for Students program, some commissions include a workshop run by the artist with students. And other artworks provide other ways for students to interact: Mnemonics by Kristin Jones and Andrew Ginzel at Stuyvesant High School includes 400 glass blocks scattered throughout the building. When it was installed, 88 of those boxes remained empty, waiting to be filled by future classes, so every year until 2088 the graduating class will leave its mark in a glass box.

Such projects are far removed from early art in New York City public schools. The first professional art on school walls, Cohen said, were seals, many of them quite elaborate, created for the individual school. Then in 1905 the Board of Education commissioned two murals by Charles Turner entitled “The Opening of the Erie Canal,” for a new high school on Manhattan’s West Side named for DeWitt Clinton, whose signature achievement was the building of the canal. (When Clinton moved to the Bronx in 1929, the murals did too.) Murals followed at other schools, notably Washington Irving High School near Union Square.

The New Deal’s Works Progress Administration and Works Projects Administration in the 1930s and ’40s offered a major boost to school construction in the city—and to art in schools. Murals still dominated but, Cohen writes in her 2009 book Public Art and Public Schools, the works addressed broader themes. In a move that resonates today, they tried to capture the diversity of the city, Cohen said, with Seymour Fogel “giving equal weight to the musical traditions of Europe and Africa” in his murals at Abraham Lincoln High School in Coney Island.

Art continued to be part of public schools in the 1950s as the city launched an ambitious construction plan. In a break with the past, many—such as Hans Hofman’s 64-foot mosaic mural outside the High School of Graphic Communication Arts on Manhattan’s West Side—were strikingly abstract, much to the dismay of some.

The social movements of the 1960s were reflected in perhaps the city’s most ambitious art in schools project: The construction of Boys and Girls High School in Bedford-Stuyvesant in the 1970s. Up until then, only one Black artist—Charles Alston—had received a commission for a public school mural in New York City.

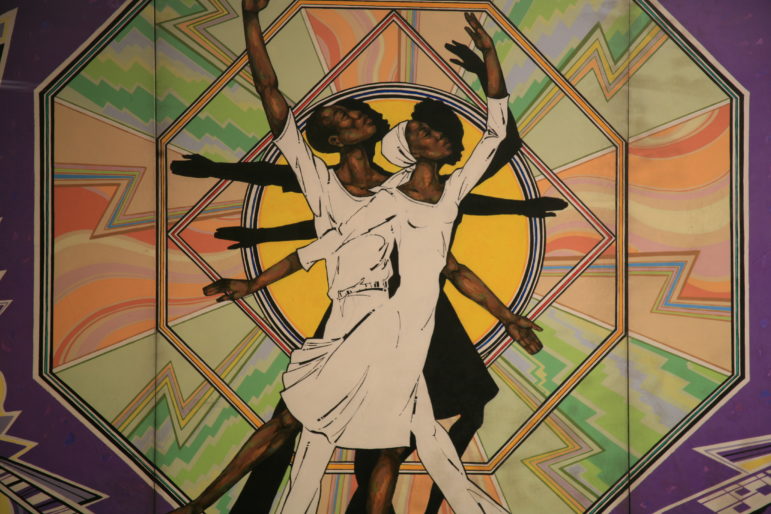

With a design calling for work by nine African-American artists, Boys and Girls marked a new era. One of the artists, Brooklynite Ernest Crichlow, was the consultant and lead artist. He created a 25-panel mural in acrylics on masonite outside the school. Other works included Ed Wilson’s “Middle Passage,” a series of bronze relief on curved concrete panels depicting the horrors of the voyages that brought enslaved people to the United States.

Above: Works on display at Boys and Girls High School in Brooklyn. From left to right: Eldzier Cortor’s “Dance, Music, Art”; An untitled mural by Ernest Crichlow; Acrylic panels by Vincent Smith; Ed Wilson’s “Middle Passage” (Photos courtesy of the NYC School Construction Authority)

Despite such projects, the push for public art was scatter-shot until the establishment of Percent for Art, with strong support from Mayor Ed Koch, in 1982. The Board of Education, initially somewhat slow to come on board, became more involved, particularly after the creation of Donna Dennis’ “Dreaming of Far Away Places: The Ships Come to Washington Market” outside PS 234 in Tribeca in 1988. “It was really revolutionary because they were turning over the design of the fence to an artist and you can’t have a school without a fence,” McGregor said.

This is the sixth city administration since the installation of that fence. Duvergne and Henry both said the program will go on. The new administration “will continue to stress that artwork needs to be inclusive of all communities,” Duvergne said. “We have to find ways to make people feel included.”

On a June morning, workers pushed trollies with boxes of ceramic tile into what will be the lobby at PS 320, a nearly completed building a block from the Sheridan Expressway in the West Farms section of The Bronx. Inside, as tile setter Mariusz Czartoryjski positioned about 1,200 pigmented tiles, a mural took shape on two adjoining walls.

An orangey river slices through the lower left corner. One section depicts a boat bobbing on water. Nearby, one sees a chest with an Islamic geometric design and a staircase. The work, “The Bronx Through Time” by Natalia Nakazawa, combines a cityscape incorporating designs from textiles with depictions of the nearby Bronx River. Plain white tiles sprinkled around will be replaced by mosaics of monarch butterflies made with glass pieces that will look “like little gems that pop out,” Duvergne said. The butterflies were selected, she added, partly because “they move from country to country.”

For Duvergne, one real test of the project is how children react to it. “What is success for me is to see a child come into a school for the first time.” The child is feeling stressed and apprehensive but then she sees the art, Devergne said, and declares, “This is it. I want to go here.”

In September, when students walk into PS 320 for the first time, Nakazawa’s work will be put to that test.

Above: “The Bronx Through Time” a tile mosaic by Natalia Nakazawa being installed at the new PS 320 in The Bronx. (Photos by Adi Talwar)

City Limits’ series on the people, places and politics of New York City’s five-borough art scene is supported by the Laurie M. Tisch Illumination Fund.

2 thoughts on “The Art Treasures Behind NYC’s School Doors”

Great story. Who knew? Should have tours. I worked at a well known school where the principal was removed after he painted over very old murals depicting early US history.

See The Decorated School for an international perspective on this phenomenon. https://www.amazon.co.uk/Decorated-School-Essays-Culture-Schooling/dp/1908966246