After two pandemic years that wrought havoc on all education but particularly on arts classes, advocates and educators have mounted a drive to win more—and more permanent—funding for visual art, music, dance and theater in the city’s public schools.

Adi Talwar

Teacher Sekou O’Uhuru leads a drumming lesson at Bronx Community Charter School.City Limits’ Art at the Limits series explores the people, places and politics of New York City’s five-borough art scene. Supported by the Laurie M. Tisch Illumination Fund.

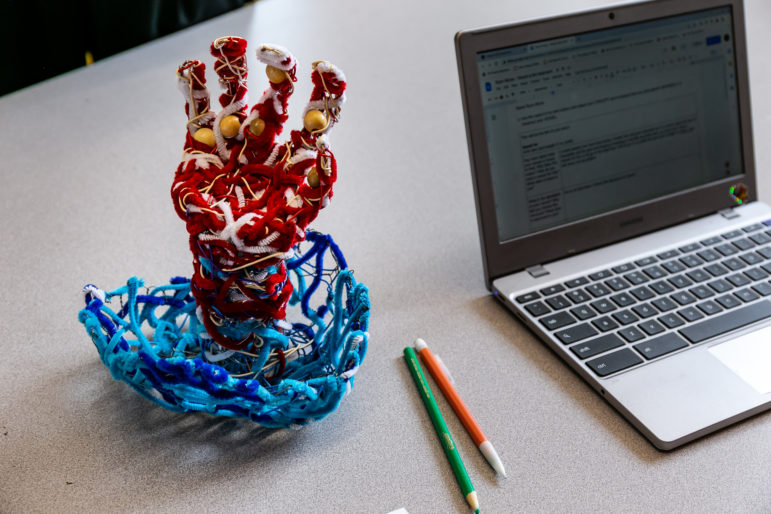

In a sunny Bronx classroom, eighth grader Niazarai Vargas uses chunky yarn and other materials to create a red, white and blue heart about the size of a soccer ball. But it’s more than a heart: It’s a vessel to hold her feelings, including heartbreak. Creating it, she said, was “like a burden being lifted.”

Across the hall, another group of eighth graders moves as dance teacher Khalid Hill issues instructions. “Open up,” Hill said. “Kids, make an L with your arms.” Getting the steps and gestures right has been a challenge, he said, because many of his students hadn’t moved for a year and a half.

In a third classroom, about 15 eighth graders sit in a circle, some with straight-sided African drums between their knees, others with buckets that once held joint compound. Regardless of their instruments, the students’ drumsticks pound out beats that reverberate through the room and beyond, all but daring visitors to start dancing.

Arts are key at Bronx Community Charter School in Norwood, which serves grades K-8. Children not only take arts classes but also have time every day to work with materials to create their own projects. Student self-portraits hang over the reception desk, an art installation on activism looks out on Webster Avenue and graduating eighth graders collaborate on murals that classes to come will admire for decades.

Not many New York City students have access to this kind of arts education, but many advocates and artists and some public officials think they should. After two pandemic years that wrought havoc on all education but particularly on arts classes, they have mounted a drive to win more—and more permanent—funding for visual art, music, dance and theater in the city’s public schools. For now, they are focusing their attention on the 2023 budget being negotiated between the Adams administration and City Council, where schools are bracing for expected cuts.

“The city must invest in our students’ future and guarantee that every young person—no matter where they live or where they go to school—has access to the arts,” Kimberly Olsen, executive director of the NYC Arts in Education Roundtable, which is spearheading the effort, said in a statement earlier this spring.

Arts education in an art capital

Despite New York’s many museums, galleries, theaters, concert halls and design studios, the arts often get short shrift in the city’s schools. With limited time and resources, schools may see art not as a high priority but as a way to give students a break and free up time for classroom teachers to prepare for the more serious topics ahead.

“Most people think art is really nice and if we had the money and the space, it would be great,” said Linda Louis, an associate professor of art education at Brooklyn College.

During the Bloomberg years, arts took a hit. Schools concentrated on subjects evaluated on standardized tests, and many of the new small high schools that emerged in that era—part of the administration’s efforts to shutter large, lower-performing schools—did not have enough students to offer a varied arts program.

In 2007, principals were no longer required to use some money that had been set aside for the arts on the arts. A 2014 report by then City Comptroller Scott Stringer reported sharp declines in spending for arts and cultural institutions working in schools and for art supplies and equipment. At the time, 28 percent of city schools did not have a single certified arts teacher; 42 percent of those schools were in the South Bronx or Brooklyn, the comptroller’s report found.

Funding began to recover during the de Blasio years with a record approximately $460 million budgeted for arts education in 2019-20—up from around $313.8 million during Bloomberg’s last year in office—though because of the COVID school shutdown, much of that 2020 money was not spent. And despite such gains, in 2018-19 about two-thirds of New York City principals felt arts funding was not adequate, according to data the Roundtable compiled from a city survey. The city’s annual Arts in Schools Report found that only about a third of middle students met the state requirement that they take courses in two different arts disciplines with a certified teacher.

And those arts teachers were often stretched thin. “Elementary school arts teachers can have 750 students and maybe a cart. If you have a room, it may not have water,” Louis said. “Funding is a huge factor.”

Then the pandemic hit. With the state education department waiving certain requirements after schools closed in March 2020, elementary schools did not have to provide a minimum amount of arts instruction. Many schools cut back on dance and theater in particular, and arts teachers were often assigned to other subjects.

The arts were not entirely abandoned. Parent groups and others assembled packets of material for home-bound children while students scrounged things from around their homes and enlisted parents in performances. The New York Community Trust awarded grants to four non-profits arts organizations to develop 345 lessons to teach arts remotely.

“It was amazing to see kids rehearsing a musical or giving a puppet show in their living room,” said Leigh Ross, program officer at the New York Community Trust. Some teaching artists taught remotely. “It required tremendous creativity and ingenuity. You had to be so agile.”

She added, “Despite all of the many challenges, what I heard again and again from grantees was that children were responding very positively. They were looking forward to their arts classes.”

Bronx Community was determined to keep arts programming even when its building was shut, said co-director Sasha Wilson. The school distributed packages of art materials so children could paint and make prints, and involved parents whenever it could. Dance continued over ZOOM, and drumming teacher Sekou O’Uhuru got drum pads for students so he could teach pieces over ZOOM and then listen to each student individually. Though they could not perform as an ensemble, “The kids continued to progress as musicians,” said Wilson.

Adi Talwar

Bronx Community Charter School students practicing their drum skills.Overall, though, the pandemic’s effect on the arts throughout the city was “devastating,” Olsen said. “Excellent arts education was still happening but only for some of our students.”

With students back in classrooms, art education is returning as well. “As we emerge from the pandemic, the arts are a critically important outlet of expression, connection, and healing for our young people,” Department of Education spokesperson Jenna Lyle said in an email. The agency has said it budgeted $429 million on arts education in the partly remote year 2020-21 and, Lyle said, “looks forward to continuing to prioritize arts education across all NYC zip codes.”

Arts education advocates and their allies on the City Council want arts to come back stronger than ever in 2022-23. Led by the Roundtable with its “It Starts with the Arts” campaign, they are pressing the city to increase the allocation for arts education to $100 per student, up from the education department’s current $79.62. The campaign also wants the department to require schools to spend that money on arts, since the DOE currently allows principals to divert the money to other uses.

In addition, the Roundtable’s campaign calls for the city to use 20 percent of the money from the federal government’s American Rescue Plan Act Academic Recovery to expand arts instruction and also seeks to restore the $24 million cut from Arts Services in 2020. This covers items such as arts grants aimed at students with disabilities and multilingual learners, and additional materials and partnerships.

In its response to the executive budget, the City Council endorsed the $100 allocation—and requiring schools to spend it on the arts—but said it could come out of the federal money.

The Roundtable, though, worries that under that scenario the increase in arts funding could vanish when the rescue money does. Olsen said they want the money to come from general school revenues to ensure that it is permanent. The rescue plan money, she said, “is a great bridge to have schools see what equitable arts education looks like,” but the Roundtable wants to bring more stability to arts education in the city.

While it is not clear whether the final budget will include the increased money, the $100 threshold “is a modest request and I think the schools want it… My sense is school leaders absolutely want more money for the arts,” Ross said.

Appearing before City Council, Lindsey Oates, chief financial officer for city DOE, said the department would review the Council’s proposal of $100 per student and has put a high priority on arts education in spending the federal stimulus money.

Some of that money goes to arts organizations, which play a major role in schools. About 400 cultural organizations partner with city schools in arrangements ranging from field trips to visiting artists to in-depth collaborations on performances by students.

Adi Talwar

A student-created work at Bronx Community Charter School.Healing through arts

As schools struggle to help students suffering from isolation and even trauma catch up academically and adjust mentally and socially, some might question whether arts education is the most pressing concern. But, advocates say, it is not an either-or question.

Art engages students and can get them excited about learning. It can provide new perspectives on so-called academic disciplines. Most pragmatically, arts is big business in New York, so raising students to be creators and consumers of it has a certain economic logic.

Creating has value in its own right, said Louis. She talks about “a tremendous sense of accomplishment” in bringing something new into being, such as “mixing red and yellow and making a mountain lion kind of orange.”

“Making is disappearing from our culture,” she said. “If you can make something that didn’t exist before, that kind of agency is going to make you a learner.”

Then there is the value of art in helping students re-emerge from the trauma of the last two-plus years and re-engage with being out in the world and around people.

“Art provides some important opportunities to process grief and … grapple with what happened over the last couple of years,” said Ross.

To channel that, the Partnership with Children is working with four elementary schools in Brownsville, Brooklyn, to launch a three-year theater program where teaching artists, social workers and classroom teachers will work with students. Meredith Sherman, vice president at the partnership, said the idea is “to provide social-emotional learning through the arts.” Brownsville was selected partly because COVID-19 struck the area particularly hard.

“We can’t expect every child to let their thoughts and feelings [out] through words. Arts give such an opportunity for expression,” Sherman said. The program centers around theater, she said, because “theater encompasses other arts and theater relates so well” to the English language arts curriculum.

While arts has always been a focus at Bronx Community, Wilson said they now may be more important than ever. “Our arts classes allow for a certain amount of messiness, which is important now and a certain amount of working things out,” he said.

At the other end of the art room at Bronx Community, Jayla Gonzalez displays a slightly bloodshot eyeball with a green iris. It’s a vessel, she says, for grief and loss. Her grief is not about what people might assume as we enter the third year of the pandemic, but that’s okay with Jayla.

“I have my own reasons for doing it but other people will see it differently, which I find refreshing,” she said.

City Limits’ series on the people, places and politics of New York City’s five-borough art scene is supported by the Laurie M. Tisch Illumination Fund.

One thought on “After Tough Time for Art in City Schools, Advocates Seek More Funding”

THIS ARTICLE SUCK