“Concerns about the creation of ‘mega jails’ have hounded the plans to close the jails on Rikers Island since before the historic vote in 2019. It has served as a useful boogeyman for opponents of the Rikers closure plan, especially in Manhattan. It’s also a fabrication.”

rikers.cityofnewyork.us

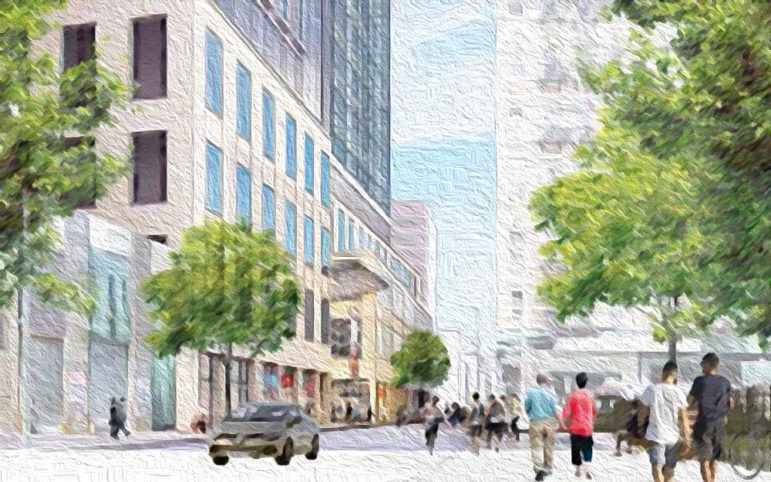

“Concept art” for the new Manhattan Detention Facility planned for Baxter Street.On a still cool but bright recent spring day people opposed to a new jail facility in Lower Manhattan rallied against the plan to get thousands of people out of the deadly, decaying facilities that are Rikers Island.

This is obviously not their framing of the situation. Activists, primarily from the adjacent Chinatown and Little Italy communities, have been in a pitched public relations battle to fight the demolition of “The Tombs” jail facility. Their attempts to stall the installation of fences and scaffolding comes after Mayor Eric Adams’ administration has given the go-ahead for demolition in Manhattan to move forward, joining the other sites in Brooklyn, Queens, and the Bronx already underway. All four sites must be cleared to make way for new facilities needed for the jails on Rikers Island to be shuttered forever by August 2027.

Local opposition to development is almost a given in New York City. The jail facility fights, which began the year leading up to passage of the land use plan to create the new facilities, are tinged with an additional resistance to the people inevitably being housed in them. Never mind that, like the Manhattan site, three of the four locations are pre-existing jails that have been in these communities for decades. It’s bad enough that the disruption of major construction is coming, but for it to house people accused of crimes is too much for some residents.

Were these simply new versions of what exists now on Rikers Island, their arguments would ring more true. That the protest over the facility sizes and their supposed local impact on communities is a misdirection for biases about the people that end up in jail hollows out the legitimacy of their stated concerns. Yet their fixation on the exterior of the buildings as a stand-in for cruel, inhumane views unintentionally highlights a critical concern totally absent in today’s discussions about Rikers and its closure. Like so much else in life, it’s really what’s on the inside that matters most. In this case, what actually goes into these new facilities represents a critical step towards keeping them from becoming new mini-Rikers.

Research and anecdotes from those who have lived through the experience speaks to the negative effects and outcomes that loud, institutional, sprawling, artificially lit, malodorous environments like the jails on Rikers lead to. These spaces help breed the culture of violence and danger–for those detained and those working there alike–that has become the all-too-familiar hallmark of Rikers Island.

Ensuring the new physical spaces did not repeat these design failures was at the forefront of everyone’s mind as the process of planning new facilities began. A team of city officials, architects, activists–including formerly incarcerated individuals–and correction leaders were tasked with creating a building program that supported necessary social and educational programming. To do this, the team visited newly constructed precedents within the US–from California to Florida–to see how they addressed similar physical space constraints, and to understand how New York could do even better. Officials went abroad, to Norway and Amsterdam, where they saw jails that utilized supportive physical spaces and embodied the kind of caretaker culture that the new facilities here must realize.

The interior design goals became clear: naturally lit, open, communal spaces that lend themselves to programming, direct service, and therapeutic priorities for those detained, while supporting correction officers with better work facilities, including gyms, respite areas and more comfortable meeting spaces. By investing in an environment built to promote safety and overall health, a critical foundation is laid on which a new culture can be built. Culture change is not an issue of bricks and mortar, to be certain. But the physical environment either supports or hinders culture change goals.

Creating this foundation means building structures that embody these goals. Ensuring that the new facilities are able to deliver all the necessary space to support education, social services, plentiful access to natural light, spaces for families to convene, and community centered ground floor programming (retail or community space, for example) requires buildings that are proportional in size to the ambitious goals set for them. Concerns about the creation of “mega jails” have hounded the plans to close the jails on Rikers Island since before the historic vote in 2019. It has served as a useful boogeyman for opponents of the Rikers closure plan, especially in Manhattan. It’s also a fabrication.

In truth, the new facility replacing The Tombs will not be the largest building in the neighborhood by far. Two Federal buildings around the court are taller, with the 500 Pearl St. court building standing at 462 feet and the multi-use Jacob K. Javits Federal Building rising to 584 feet. Three blocks away, the Civic Center’s crown jewel Municipal Building is just over 550 feet tall. And nothing rises over the neighborhood quite like the 433-foot Confucius Plaza Apartments, four blocks down from the jail on Bayard Street. With its maximum height of 295 feet, the new facility won’t even be the tallest building on its block: 100 Centre St., home to the state courts and the Manhattan district attorney’s offices, stands adjacent at 354 feet.

Critics have also noted that the new facility will actually have fewer beds that are currently available in The Tombs. This is somehow meant as a critique. What it actually shows is that the increased square footage isn’t about detaining more individuals within–it’s about providing the proper space for people to utilize programming, health clinics, and recreation.

The decisions the administration of Mayor Eric Adams makes in the coming weeks and months will determine whether these facilities recreate past failures or embody a new model. Everything from what types of bathroom fixtures are installed and how institutional they look, to whether there is a real commitment to a direct supervision model–officers stationed on the housing unit floors, interacting with detainees without barriers–are critical to demonstrating that New York City is serious about building a new system.

The culture of Rikers Island must also end with its closing. The first test of whether that’s possible will be holding firm to the commitment of a radically different environment for detainees and officers alike. In August 2027, when the jails on Rikers Island are forever closed, people in custody must be entering new facilities that are supportive, rehabilitative, and in stark contrast to the carceral buildings that have plagued New York City for decades, if not centuries. If the interior space designs are corrupted and allowed to recreate even a small measure of the institutional bleakness and inhumane isolation of Rikers we will truly and simply be trading one set of buildings for another.

People in Chinatown and in neighborhoods across New York City where the facilities will be located do have righteous demands and deserve a responsive government that takes seriously construction and quality-of-life concerns such as parking, noise, and traffic. But in focusing on stopping these facilities over ensuring that these buildings are on time to meet the 2027 closure of Rikers, well designed to meet the stated goals for transformation, they are–even if unintentionally–fighting to condemn another generation to the unacceptable and deplorable conditions of Rikers Island. That is a future that no New Yorker should accept as an outcome.

Stanley Richards is deputy chief executive officer at The Fortune Society.

READ MORE FROM THE ARCHIVES:

2 thoughts on “Opinion: Planned Borough-Based Jails are a Chance for a ‘Radically Different’ System”

3/4 jail sites will be appropriately placed except for the Bronx location. The Bronx jail should have been developed adjacent to the courthouses on E 161 Street. The city chose the site in Mott Haven over a mile from the Bronx judicial district because the previous council member was against it and it would have required a more expensive project. So the Bronx just has to deal with the poor location. Part of the original primary criteria was to keep the new jails near the existing judicial facilities.

The large Concourse Plaza across the street could have been redeveloped, it’s mostly parking and has an enormous footprint. New commercial storefronts, offices, and community facilities could have lined E 161st Street, the existing demolished. Parking underground. Jail on top. Skybridges to the courthouses. Maybe even a residential component facing Concourse Village on the south part of the lot.

The selected site, a tow pound, should have been redeveloped as high density mixed use to anchor the increasing residential transformation of the mostly industrial corridor east of St Mary’s Park. Time will tell how a jail will impact the neighborhood.

The Chinatown location is a hilarious farce but the Kew Gardens, Queens site is absurd.

The holding area that used to be there was small. It’s closure led to the area moving on so that there is no infrastructure to support a jail to bring thousands of people daily. And the argument that you’re just replacing one jail with another is like saying you’re just going to fit Central Park into another park whose area is 1/50 the size.

So how ludicrous is it? The Kew Gardens jail will have ZERO actual outdoor areas for inmates. They are building a 1,100 vehicle garage at a difficult to access space that is right smack at the Kew Gardens Interchange, considered the top ten worst traffic areas in the entire country. That it is also a hub to JFK makes me laugh my butt off because any mistake they make, and it will happen, means a criminal suspect can quickly jet out of the area and the jurisdiction!

Anyone who looks at a map can also see that the jail local is inaccessible in almost every direction except for one main road and a subroad. Imagine thousands of cars trying to get in and out of parking. Watching the DOT try to explain this catastrophic mess will be funny. Since the neighborhood is primarily residential, it’s going to be really fun to watch how criminal inmates and their families go in and out of what was a low crime community. Everyone knows this is going to be a total disaster but they don’t care. They will grab Riker’s real estate, develop it, and who cares if middle Queens becomes a criminal cluster that will never recover. And it won’t.