“We must demand systemic changes to ensure that incarcerated mothers have the opportunity to be part of their kids’ lives. Not just during Mother’s Day, but all year round.”

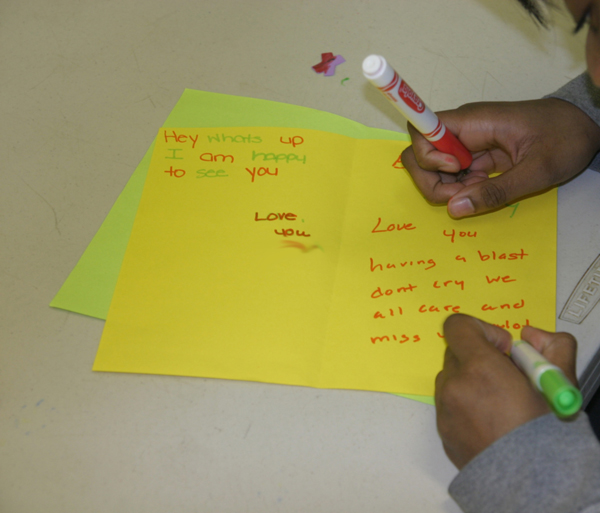

Patrick Egan/City Limits Archives

A child preparing to visit New York’s Albion prison prepares a card for her mother, 2010.For most moms, Mother’s Day is a celebration spent at home surrounded by children and loved ones. For hundreds of thousands of mothers in the United States, that’s not the case. In New Jersey, many of the state’s approximately 2,000 female inmates are mothers of minor children.

As worrisome, most of these mothers will not even see their children this year on Mother’s Day. In research published this June in The Prison Journal, we found that nearly two-thirds of mothers in prison in New Jersey hadn’t ever received a single visit from their children. And due to the prohibitive costs of prison phone calls, many won’t even be able to hear their children’s voices on their special day.

When we asked mothers about this, they shared a range of explanations. One mother said that she doesn’t like it when family members visit her because “it is hard on [her] when they leave.” Others say that they have no visitors by choice, one woman going as far as saying that she requested her family not come.

We found many women don’t want to expose their children to the harsh realities of prison life. This is why having a space especially assigned for kids to visit, with items such as toys and books, could help alleviate the stress and anxiety that surrounds some of these visits.

There are several reasons this is a problem in need of a solution. For one, women are the fastest-growing segment of the imprisoned population, with an estimated 231,000 women incarcerated in the United States, according to the Prison Policy Initiative. Additionally, a majority of women in state prisons and the vast majority of women in jails are mothers of minor children, for whom they had been the primary caretaker prior to their imprisonment.

For this growing segment of the imprisoned population, research shows numerous problems associated with a lack of visitation and contact with family and children. Child separation is related to psychological symptoms like depression, guilt, anxiety, and feelings of distress and isolation. Our New Jersey survey found contact with children to be associated with lower levels of self-reported mental health symptoms. For instance, women who reported more frequent calls with their children also disclosed lower levels of depressive symptoms, feelings of worthlessness, and hopelessness about the future. And there is evidence to suggest that these benefits extend beyond these women’s sentences, with a study finding that keeping in touch with family and children reduces the likelihood of post-release re-offending by almost a third.

Our research leads us to the conclusion that prisons and jails need to emphasize the importance of visitation and other forms of communication between mothers and children, and that they should enact practices to facilitate them. Unfortunately, correctional policies supporting visitation and other forms of contact between mothers and children are severely lacking.

To support women between visits, correctional systems in New Jersey and across the country should enact policies that make other forms of communication, such as phone calls and letter writing, easier. One first step would be to restructure the prison phone call system. Prisoners are a captive market, preys of monopolistic private companies contracted by state agencies. While the FCC has been able to cap the cost of interstate calls at $0.21 a minute for debit/prepaid calls and $0.25 a minute for collect calls, states can and should set caps on intrastate calls, which make up 80 percent of all inmate calls.

Prisons and jails also should do more to facilitate child/parent contact. In recent years, advocacy efforts, such as the “National Black Mama’s Day Bail Out,” have shone the spotlight on the plight of incarcerated mothers separated from their children. But we still have a long way to go. We must demand systemic changes to ensure that incarcerated mothers have the opportunity to be part of their kids’ lives. Not just during Mother’s Day, but all year round.

Irina Fanarraga, M.A. is a doctoral student in the Criminal Justice Program at John Jay College of Criminal Justice / The Graduate Center, CUNY. Her research focuses on intimate partner violence, corrections, risk assessment, and alternatives to incarceration.