A federal court approved the terms of a settlement agreement that requires the NYS Board of Elections create a statewide remote mail-in system so that voters who are blind, or have other print disabilities, can read and mark their ballots independently.

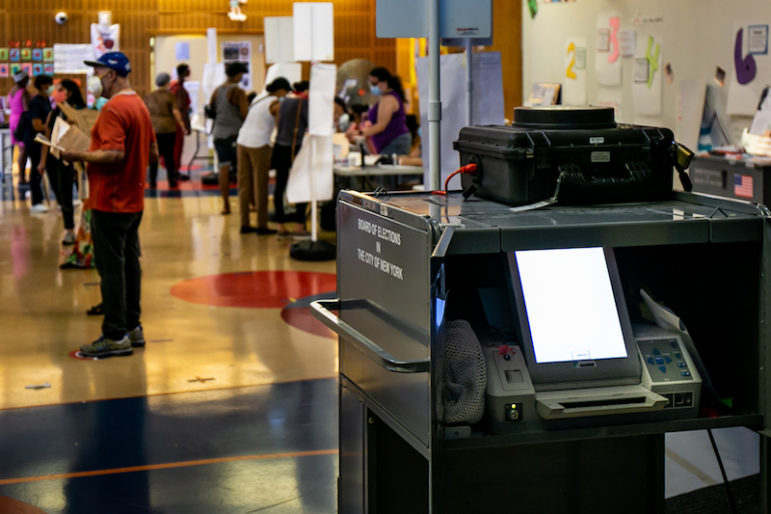

Adi Talwar

A ballot-marking device at P.S. 94 in the Bronx on Primary Day in 2020.For Sharon McLennon-Wier, casting her vote in elections hasn’t always been easy.

The executive director at the Center for Independence of the Disabled, New York (CIDNY), McLennon-Wier is blind. Voting at a poll site in-person often proved “very challenging,” she says.

There were crowds and lines to contend with, and despite the fact that every New York City polling station is required to have accessible voting equipment in the form of a Ballot Marking Device (BMD), sometimes the machine wouldn’t be plugged in yet, or it would be out of paper, or staff at the site wouldn’t really know how to use it, McLennon-Wier said.

Voting via paper absentee ballot wasn’t ideal, either. “They just mail a piece of paper to your house,” she explained, meaning she and other voters with a visual, learning or dexterity disability had to rely on another person to help read their ballots.

“My experience has been every time that I vote—and I’m 51 years old right now—if I didn’t have a family member, husband, mother, someone come with me, I could not vote,” McLennon-Wier said. “I could never ever vote independently, which is horrible to say.”

But that’s set to change. A federal court last week approved the terms of a settlement agreement that requires the NYS Board of Elections create a statewide remote accessible vote-by-mail (RAVBM) system, which would use HTML ballots compatible with screen-reader software so that voters who are blind, or have other print disabilities, can read and mark them independently.

The settlement stems from a lawsuit filed in 2020, when then-Gov. Andrew Cuomo issued an executive order that allowed all New Yorkers to vote via absentee ballot because of the pandemic. A coalition of disability rights advocates challenged the fact that the change still excluded voters who couldn’t complete a paper mail-in ballot on their own, and would have forced them to head to poll sites in-person instead.

“The pandemic really threw into sharp relief how important it was that people with disabilities have the same voting choices that people without disabilities have,” said Christina Brandt-Young, a supervising attorney at Disability Rights Advocates (DRA), one of several advocacy groups, including CIDNY, that filed the lawsuit.

Just weeks after the suit was filed ahead of the June 2020 primary election, NYSBOE announced it would for the first time offer email-accessible ballots to voters with disabilities who requested them, which could then be read and marked with assistive technology. That option has been available since then, but it’s imperfect, advocates say, since the PDF ballots are not compatible with all screen reader technology.

But under the newly approved settlement, the NYSBOE will have to establish a system that is specifically designed for such software and “is tailored to filling out a ballot,” said Brandt-Young.

“HTML websites have been coded for screen-reading technology,” that turns text to Braille or spoken words, explained McLennon-Wier. Voters will be able to use their own accessibility equipment, like adaptive keyboards, to mark their ballots directly themselves.

“That’s huge,” she said. “And why can’t people with disabilities be able to do absentee voting just like everybody else, you know—they sit in their home and mail away their ballot, right? Why can’t a person with disability have that same pleasure?”

Voters will be able to request the electronic absentee ballots using an accessible online request form up to 15 days before an election.

“There are a lot of people statewide that this is going to help,” Brandt-Young added. “And the state should be commended for making sure that those ballots are more private, independent than they were before.”

Under the settlement, the NYSBOE will need to create a portal where voters can request an accessible mail-in ballot, and to provide return envelopes that have tactile marks on them to indicate where a voter should sign (though signatures anywhere on the envelope will be accepted). The board is also required to train election workers in all 58 counties on how to use the RAVBM technology.

It’s not clear yet if the new system will be ready in time for the June primary election, which will see Gov. Kathy Hochul square off against rival Democrats like Jumaane Williams and Tom Suozzi, among other competitive races.

A BOE spokesperson said the agency “will use its best efforts to complete the procurement process and the other technical details necessary to fully implement the technical provisions of the agreement in time to meet the primary election,” in June.

If the system isn’t ready by then, the NYSBOE will offer the PDF absentee ballots it began offering in 2020. “We still have the accessible system in place that was used during last year’s elections and our goal would then be to comply in time for the November general election,” the spokesperson said.

Advocates say the change is just one hurdle in a larger, nationwide effort to make voting more accessible to people with disabilities. Even HTML-accessible absentee ballots, like the paper counterparts, need to be printed out and mailed in, meaning some voters will still need to rely on the help of another person (the NYSBOE, as part of the settlement, is required to help voters print their ballots if they don’t have a printer at home).

“We still have a long way to go with regards to accessibility,” said McLennon-Wier, including improving the in-person voting process so those who still want to cast their ballots “the old fashioned way,” can do so without issues.

This would require making Ballot Marking Devices (BDMs) ubiquitous at poll sites—as opposed to the current system, where there is typically just one at each location—and ensuring board of election workers are properly trained in using them.

“Until we get to the point where [the] ballot marking device is a universal design—where for everyone one standard machine, there’s a ballot marking machine as well—and you incorporate mass training on every machine, you won’t get to the point of having true accessibility,” McLennon-Wier said.

This story was produced as part of the 2022 NY State Elections Reporting Fellowship, with support from Center for Community Media at CUNY Newmark’s Graduate School of Journalism.