Excluded Workers Fund debit card thefts have been reported by over 70 beneficiaries, which has left some of their accounts with losses of up to $6,000.

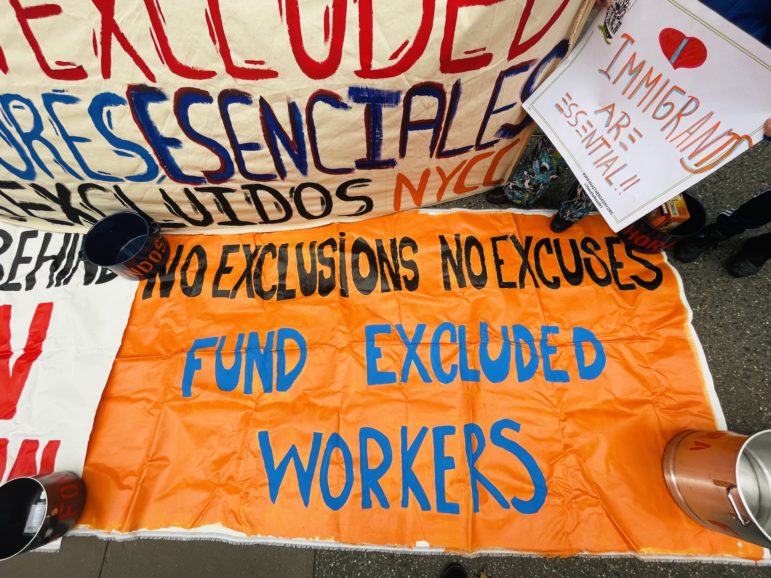

Courtesy Make the Road New York

This story was originally published by Documented on Jan. 26, 2022

Elizabeth was elated when she received a notice that she had been approved to receive financial assistance from the Excluded Workers Fund (EWF). She had gotten COVID-19 in early May of 2020 and lost her job as a house cleaner and had fallen behind on rent. She was surviving on borrowed cash from her family.

On Nov. 5, 2021, she received a debit card in the mail with $14,820 on it. “It was a blessing from God, it felt like my early Christmas present,” said Elizabeth, who is 34 years old and like others Documented spoke to for this article, preferred to use a pseudonym. She used a third of the money to pay back the debt to her family, around $5,800, and with the rest she was able to buy food, school supplies for her older son, 16, and a new backpack for her daughter, 5.

Early one December morning, she took her usual stroll to her local bank in Jamaica, Queens, to withdraw the money she depended on for food and her expenses. She put in her card and punched in her pin, and shortly after a message popped up on the ATM screen: she had insufficient funds in her account, it said. She called the company who issued the card and was told that she only had $25 left. Somehow, $3,200 had disappeared.

READ MORE: NY’s ‘Excluded Workers’ Push State for Protections Beyond Pandemic Aid

Elizabeth is one of at least 70 Excluded Workers Fund recipients who reported their financial relief dollars being stolen from their accounts through fraudulent withdrawals and purchases. Documented spoke with nine members of our WhatsApp community who lost a total of $29,437 to unauthorized transactions. Recipients of the fund started reporting money being stolen by late October, shortly after the state sent out debit cards to thousands of New Yorkers. These incidents highlight how the state government’s strategy of distributing financial aid through prepaid debit cards, which it does for programs outside the Excluded Workers Fund as well, is highly vulnerable to theft.

Documented contacted both the NYPD and Blackhawk Network, the company that the state contracted to handle the distribution of the funds. On Jan. 24, 38 days later after Elizabeth reported the card theft, Blackhawk concluded their investigation and credited her account for the funds disputed.

However, other Excluded Workers Fund card theft victims are still waiting. Diana, 40, also contacted Documented via WhatsApp and said she had reported a claim for $1466.50 for three unauthorized transactions. Like Elizabeth, she used to withdraw money from ATMs in her neighborhood of Corona on a regular basis. But around Thanksgiving, her account started acting up.

“It said that I had exceeded my limit, so I would skip a day thinking that perhaps the 24 hour cycle had not passed,” Diana said, referring to the 24 hour period that must pass between cash withdrawals.

During the first week of December, as she checked her remaining balance on her account online, she saw three withdrawals that had taken place on the exact days that she had been unable to withdraw.

She immediately called Blackhawk and began the process to dispute three transactions in the amounts of $483, $483.50, and $500 that had taken place between Nov. 23 and 26 in the boroughs of The Bronx, Brooklyn and Queens, according to a cardholder dispute form submitted to Blackhawk and reviewed by Documented.

Card Thefts On the Rise

Incidents, where individuals have their debit or credit card information stolen and used for unauthorized transactions are generally known as card skimming.

Card skimming happens when an individual tampers with an ATM by placing small devices, fake keypads, and/or small cameras to steal someone’s card information, along with their pin, Bruce Wayne Renard, Executive Director at The National ATM Council explained.

Bank lobbies that stay open overnight, like the ones that both Elizabeth and Diana had visited, are more prone to skimming due to the lack of security, Renard said. “You have to look carefully at the terminal to see if anything is altered or anything has been overlaid in the keypad,” he said. He recommends every card holder cover the keypad with one hand whenever they are entering their pin, since most of the time the pin can be stolen by small cameras placed around the ATM.

“Card skimming is charged in a couple of ways. In New York the most common ones are identity theft as a felony, grand larceny, and possession of a forged instrument,” said Jeremy Saland, a criminal defense attorney and former Manhattan prosecutor.

Data from the Federal Trade Commission shows an increase in the number of complaints of card fraud over the past five years in New York state, with a significant spike in the last three years. Between 2019 and 2020, estimated losses jumped from $87.6 million to $127.7 million and to $179.5 million in the first three quarters of 2021.

Sergeant Edward Riley, a spokesperson for the New York Police Department, told Documented that data about EWF skimming incidents was not tracked at a granular level. Riley said that stealing “and or using card information is considered Grand Larceny,” regardless of the amount.

There have been no arrests made in Elizabeth’s grand larceny case and that investigation remains ongoing, Riley said. He did not respond to questions about whether the NYPD was working with other agencies, including the Department of Labor, for the investigation.

While these types of crimes have been on the rise, there is concern among immigrant advocates that EWF recipients have been targeted given the high number of beneficiaries that had their information stolen. “Workers are getting defrauded, it’s a serious issue,” said Nadia Marin-Molina, co-executive director of the National Day Laborers Organizing Network (NDLON). She first heard of these complaints back in early December.

In December, Blackhawk notified all the recipients about a new procedure that would protect them from having their information stolen. From the moment recipients activated their card, they were able to withdraw cash from any ATM. Blackhawk made it so that individuals could not withdraw money from ATMs and instead had to go into a bank that was part of the VISA network. They would have to speak to a teller, show their card and a valid ID to withdraw their funds.

“The idea is to protect workers from more of this kind of theft,” Marin-Molina told Documented.

Not Everyone Reported The Thefts

For those who had already fallen victim to the Excluded Workers Fund card thefts, the Department of Labor implemented a process to report any unauthorized transactions, said Brayan Pagoada, youth organizer for Churches United For Fair Housing (CUFFH) in a statement.

First, individuals had to submit a complaint form on the DOL website, call Blackhawk to request a new card and a case number to dispute the transactions, notarize the form, take it to the police precinct where the unauthorized transactions happened to file a report, and then email and submit those documents to Blackhawk within 10 days.

Elizabeth had to take her daughter-in-law with her to the police precinct and notary to act as a translator while the process unfolded. She said it took her around eight days to complete all the steps and send back the report alerting of the card thefts.

But not everyone who lost money from their accounts has filed a complaint. Jaime B., a resident of Queens, told Documented that at least four of his friends had fallen victim to card thefts in the same bank located in Astoria. Around early December, he says that his friends started to see random withdrawals in New Jersey, Manhattan and other boroughs where they have never used ATMs.

“Some reported, some did not. I tell them that once they get the money, it is up to them to protect it,” he said, mentioning also that when his friends went to the 114th precinct they had seen multiple people filing the same complaints for card thefts.

“The last thing you want is someone to open lines of credit or take out loans in your name,” said Saland, mentioning that depending on how the information was obtained, it could end up on the dark web. “If you are a citizen, or if you are here with status or without status and you are a victim of crime, you do not have to allow yourself to be victimized because of that status. There are folks who will advocate for you.”

Ingrid, 38, another member from Documented’s WhatsApp community who chose to use an alias, showed Documented her statement where $6,102 was depleted from her account via online purchases done at places like Michael Kors and Bloomingdales.

Because her transactions had taken place online, it was easier for her to file a dispute as compared to transactions that were done at physical ATMs. When she called Blackhawk she had to wait until her card replacement arrived and then file a complaint, which she did on Jan. 9.

Queens Assemblymember Catalina Cruz, who represents the neighborhoods of Corona, Elmhurst and Jackson Heights, urges everyone affected by card thefts to file a report and dispute the transactions. Cruz said her office had reached out to the DOL when constituents began expressing their concerns about unauthorized transactions on their accounts.

While the actual number of EWF beneficiaries who have fallen victim to skimming practices is not known, Cruz’s office worked closely with the police to file at least 70 cases of card skimming on behalf of her constituents between late October and December. Multiple community organizations have also heard complaints from some of their members.

“What we have been working to do is to make sure that we are supporting people to get their money back, and some have already gotten their money back, but also making sure that this issue does not happen ever again,” Cruz said on a phone call.

Nova Rivera from Fund Excluded Workers Coalition said it was “incredibly disappointing” to see this scam happening after fighting so hard for essential workers to receive their money, and especially because the fund is so historic.

“We’ve never seen any program that allocates money to the immigrant community, to excluded workers and gives them cash payments like this directly. And so that’s a huge win in and of itself. And then to have that sort of taken from some workers because of this issue, it’s really disappointing,” she said. “It can definitely provide a lot more unnecessary stress and anxiety.”

But Rivera still regards the Excluded Workers Fund as a successful program, and noted that the proportion of people getting scammed is “pretty small” compared to the proportion of people who have benefited from the fund.

Card Thefts Reports That Were Rejected

Armando Isidoro, 52, a Mexican native who has been living in The Bronx since he arrived in 1993, contacted Documented desperately asking for help. Between Dec. 3 and Dec. 6, based on the dispute form filed with Blackhawk and reviewed by Documented, $3889.50 had been spent from his account in 10 unauthorized transactions.

He felt saddened to know that someone had taken his information and taken advantage of him at a time when he was most vulnerable. Since the pandemic started in 2020, his employment at a cleaning company had suffered erratically. There were weeks when he had no work.

In August 2021 he suffered an injury on his toe, due to his diabetes, which required him to go to the hospital. The doctor told him he needed to rest for a few weeks. When Isidoro asked his employer for unpaid time off, he was fired, he said. Ever since then he has been unable to find work, although he has been constantly looking for it.

When he was approved for the funds he felt relieved, but also uneasy because he never liked to receive help from anyone. “Ever since I got to this country I have always worked and lived from my own money. But sometimes our illness can put us in these situations,” he said.

The $14,820 that he received substituted his lost salary and allowed him to pay his monthly rent and utilities, which he shares with his brother. When he found out that his money had been taken from his account in early December, he could not believe it had happened to him. He had heard from other recipients that their accounts had been affected, but it did not feel real until that cold winter morning when his balance dropped drastically.

“It feels like a second pandemic that is only affecting undocumented people,” he said via a phone interview. He filed the police report and complaint form with Blackhawk during the third week of December.

On Jan. 19, he received a message from Blackhawk that said: “We have concluded our investigation based on the facts of your case. After review of the cardholder’s dispute claim we have found that no error has occurred. As such, your case is considered resolved and closed.”

Isidoro does not know what is going to happen, and worries that the money he saved and what was left of his EWF grant won’t last long. “My head is working overtime thinking about where I am going to find a job,” he added.

A representative from Blackhawk directed an inquiry into the number of card thefts complaints submitted by EWF recipients to the Department of Labor (DOL). The DOL told Documented that “The New York State Department of Labor does not comment (confirm nor deny) on potential or pending investigations.”

“I just want them to help us. Not just me, but everyone,” Diana said, adding that she is $5,500 behind on rent. “There were a lot of people that fell victim to this and the right thing to do would be to give us the money back.”

One thought on “NY’s Excluded Workers Fund Hit With Debit Card Thefts”

Hi I got the same problem I can scam also I need to know where to make the report I send in all the documents they need and the case is still not resolve from December 2021.please help