“Wayne was an absolutist—moral, faithful, tea totaling, tenacious—a believer in redemption, with reportorial standards beyond reproach. No short cuts, no cheap rumors—only shocking facts; never going with a piece unless certain of its accuracy; smiling rather than taking umbrage when reporters chased his work without citing him.”

Courtesy of Fred Smith

Left: Wayne Barrett and the author at the release party for Barrett’s 2001 book RUDY! Right, the author and Barrett at City Limits’ 40th anniversary gala. CityViews are readers’ opinions, not those of City Limits. Add your voice today!

CityViews are readers’ opinions, not those of City Limits. Add your voice today!

Wayne Barrett died five years ago. We lost a “detective for the people.” I lost a friend.

I contacted him a half-life ago on a Board of Education phone to see if he’d be interested in doing a complicated story involving New York City’s test results.

Little did I know this would start a beautiful friendship. Little did anyone know that over the next 20 years, Wayne would take the measure of the three biggest egos in New York City: Ed Koch, Donald Trump and Rudy Giuliani.

I reached out to Wayne because of his Village Voice columns in the late 1970s. Other newsies said my subject was too “arcane.” But Wayne took the call. He expanded my analysis, showing how reading scores had shot up sharply in 1980 and 1981. The reason was that the tests had been over-exposed and low scorers were left out of the test population.

This was early in Wayne’s career, when he was perfecting the use of interns to help develop articles, and they were learning real-world lessons about what went into investigative reporting.

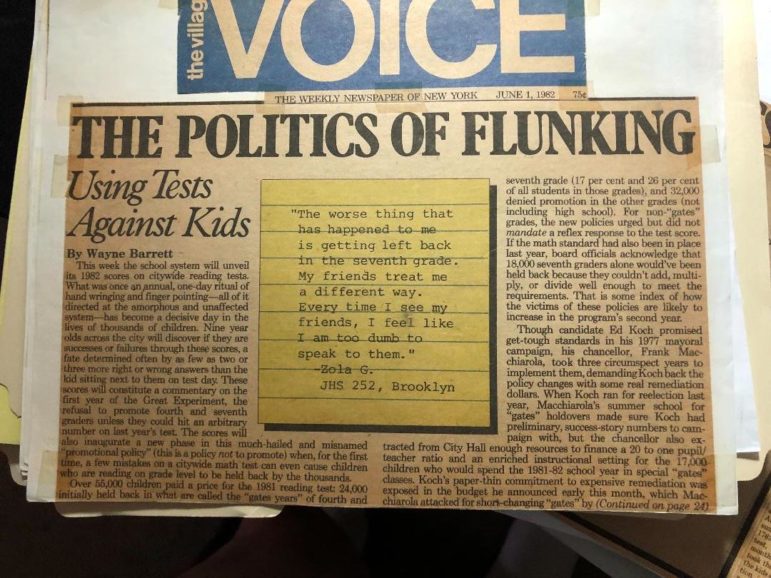

Wayne’s June 1981 front-page report, “City Cheats on Reading Tests,” ran. It was the first deep analysis of the way the testing program had been misused to yield inflated scores. Koch asked to be judged based on test performance. He got what he wanted—more than half of the kids above the norm, and his re-election in 1981.

Recently, as I re-read the dusty 40-year-old piece, it reawakened me to how Wayne’s writing went from revelation to prophesy. He goes beyond immediate falsehood, and decades later I realize that he points to dangers he foresaw—in this case, the waste of classroom hours on test preparation and the pressure put on students, teachers and principals to do well on the exams.

Our bond formed early on. We both took BOE jobs in the late ‘60s; were doting fathers of sons, Mac and Sam; addicted rooters for underdogs—he, the Red Sox and we, the Jets, for whom I had begun to keep official stats. That was the alchemy of our friendship.

In addition, Wayne liked my backstory. In 1976, I brought Controller Harrison Goldin evidence that the citywide testing contract had been rigged. He ended a fix that had cost the city $2.5 million. My good citizenship netted me an unsatisfactory rating. But I got a one-year leave to work for Goldin.

In 1982 I brought Wayne a box full of memos, interim reports, bylaws, etc.—his lifeblood. The material pertained to the “Promotional Gates” that Koch had been hyping as a return to tough standards. The Gates would retain students in the 4th and 7th grade if they were below the norm in reading. It turned out to be a futile design, sold with ballyhoo—a policy in search of a program and resources.

It was a cruel approach which failed to deliver claimed benefits for students who were held back. “The Politics of Flunking,” Wayne’s June 1982 cover story for the Voice, provided the debunking details. The Gates were abandoned, but Mike Bloomberg and Andrew Cuomo would repeat similar mistakes despite the history lesson.

Courtesy of Fred Smith

Wayne Barrett’s 1982 story on the Koch administration’s school test scores policy.Barrett’s actions, not just his words, mattered. I asked if he’d come out on a Saturday to speak to parents at a local school about the issues we raised. He instantly agreed and cautioned skepticism about the testing program.

My source-to-reporter relationship continued intermittently when he asked me to sleuth out some BOE information on targets of interest. But the friendship grew steadily, from my inviting him to Jets training camp to dropping by for chats at his new Windsor Terrace home.

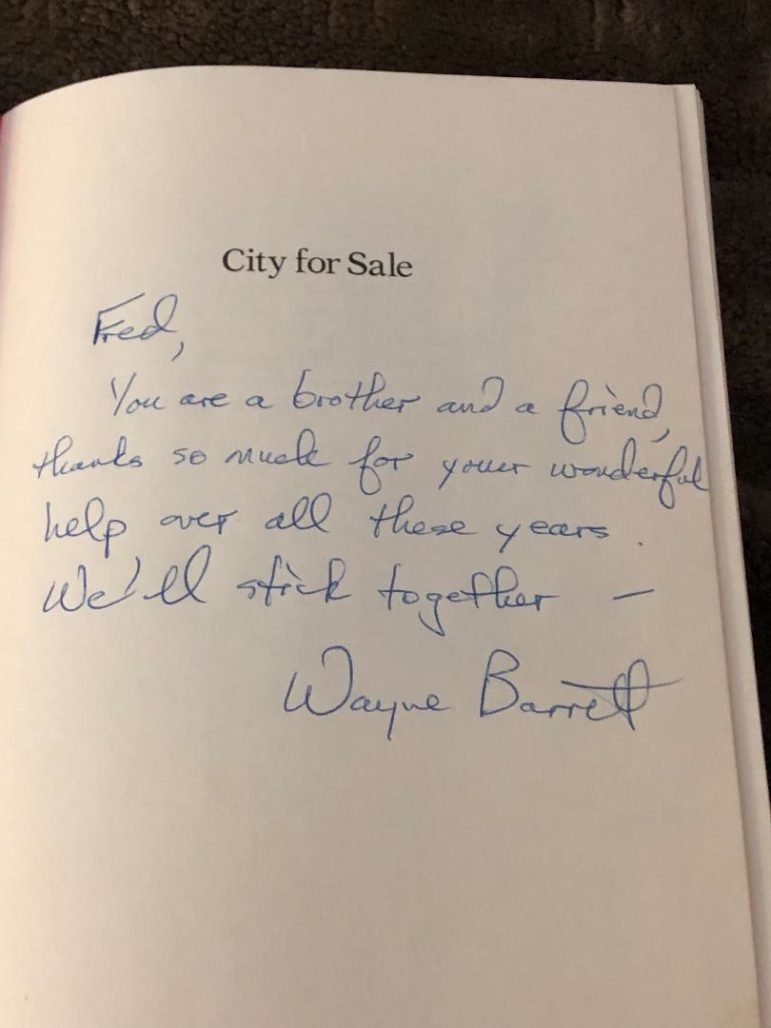

Soon he was ready to author books. The Voice had given him free rein with his writing and he had time to work with Jack Newfield on their gripping 1988 “City for Sale,” tracing the payoffs and corruption that took place under Koch’s nose.

A highlight came when he told me to come to the book signing at the Village Vanguard. I remember Gabe Pressman, David Dinkins, Murray Kempton, Jimmy Breslin and even Jackie Mason being part of this celebration. And I treasure my inscribed copy: “You are a brother and a friend…. We’ll stick together.”

Courtesy of Fred Smith

At my son’s Bar Mitzvah a few years later, I see WB flinging himself into a joyfully disjointed hora. Wayne gave a copy of his 474-page seminal work, “Trump: The Deals and the Downfall” (1992) with a card that said: “Sam, Search for truth. Struggle for justice.”

Surely, both concepts are alien to Trump, who never granted Wayne an interview as he delved into his makeup and did a forensic examination of the financial, quasi-legal games Trump played to build a sand castle empire. It was an MRI into this guy’s MO that would have spared the feds millions to trace the same blueprint.

Wayne was onto to this then-33-year-old racist and his political accomplices from the jump. He continued to dog Trump and, I believe, would have buried him in his dirty habits, tax returns and phony property valuations before the 2016 primaries.

By 1996, I’m living in a Windsor Terrace apartment a half-mile from Wayne. At times, he asks me to verify data on personnel. House-sitting, dog-walking and cat-feeding opportunities come my way. We jog in Prospect Park. He contends that home plate umpires are biased against the Red Sox. I confess that, as years go by, alluring women are more and more out of reach. He blows me up: “Smith, they never were within your reach!” We howl.

One day he wants to meet for lunch in downtown Brooklyn. He’s doing another book and needs someone to deconstruct Giuliani’s crime stats to see what’s behind the decreases that are central to the mayor’s success story. Of course, I say yes and embark on a dissertation’s worth of effort, digesting information from FBI, DCJS and NYPD reports, looking for trends pertinent to violent vs property crimes in New York and other large cities. All for one slice of pizza and a coke.

“Rudy!: An Investigative Biography” is slated for completion by Labor Day 2000, but when Giuliani’s senatorial race against Hillary Clinton crashes in May due to his medical and marital woes, the publication timetable is moved up to June. Wayne asks me to jog on the morning Rudy pulled out. He took it in stride, and finished his 468-page book against a brutal deadline. I’m particularly fond of Chapter 17, “These Statistics Are A Crime.”

Wayne was convinced there was no information that he couldn’t unearth. Proof comes when he asks me to Xerox the “Rudolph W. Giuliani Vulnerability Study.” Rudy commissioned the oppo research against himself, to anticipate weaknesses David Dinkins might use against him in his 1993 re-run for mayor. On reading the 464-page report, which identifies a “weirdness factor” in his personal life, he ordered every copy destroyed. Somehow, one copy got away.

There would be another book in 2006, “Grand Illusion,” co-authored by Dan Collins, a piercing counter-narrative showing how Giuliani failed NYC on 9/11.

Wayne was an absolutist—moral, faithful, tea totaling, tenacious—a believer in redemption, with reportorial standards beyond reproach. No short cuts, no cheap rumors—only shocking facts; never going with a piece unless certain of its accuracy; smiling rather than taking umbrage when reporters chased his work without citing him.

After 37 years, 10 years into the millennium, the Voice laid Wayne off to save money. That same day, clear-eyed Tom Robbins, the closest anyone was to being Barrett’s peer, took his rake and quit the eviscerated paper.

In the ensuing years Barrett wrote on and offered commentary in TV interviews and documentaries. Sadly, his health began to fail. I would drive him to local doctor visits. He talked with animation but gradually moved from a chair and oxygen to his bedroom. We’d kibitz. He never betrayed self-pity. On my goodbyes, I wanted to hug him, but settled for pinching his big toe.

Adi Talwar

Wayne Barrett addressing the crowd at City Limits’ 40th anniversary gala, September 2016.

City Limits honored Wayne in September 2016. Barrett spoke, his indignation, passion and vision undimmed, summoning the strength to call out cable news networks for coverage less concerned with truth-telling than gaining the largest ratings. After that, he asked me to wheel him away from the loud music.

Last year, “Without Compromise,” was issued, a collection of articles gathered from Barrett’s archives by former intern Eileen Markey. Get a copy.

Near the end, ever-caring Tom Robbins told me to see him. A few days later, on the eve of Trump’s inauguration, someone emailed me the news. A lung disease had silenced Wayne’s voice and ours.

Five years ago, hundreds packed the funeral service in his Brownsville church. Family, friends, interns, reporters and politicians were there. Two of his victims, Andrew Cuomo and Charles Schumer, spoke fondly of him. Mac gave a eulogy for the ages.

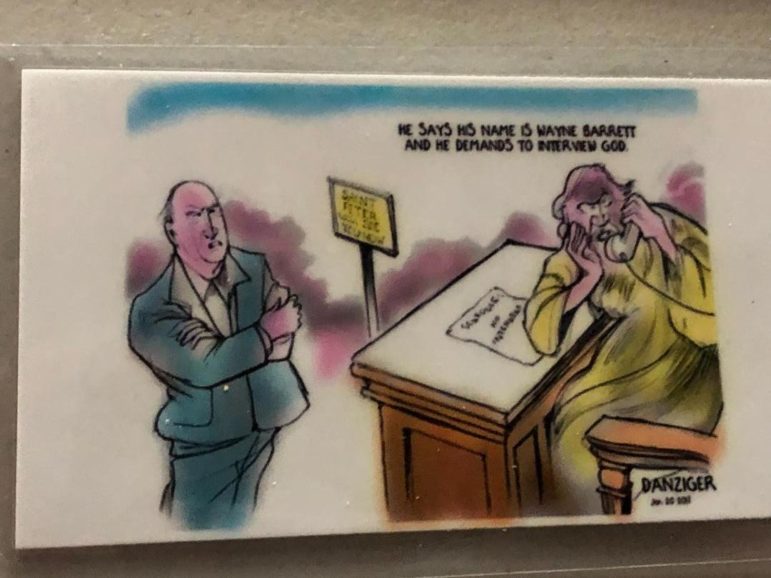

His funeral card sums it up in a political cartoon by Danziger, depicting an impatient WB and a harried, phone-in-hand, Saint Peter calling from an intake desk: “He says his name is Wayne Barrett and he demands to interview God.”

Fred Smith worked as an administrative analyst for the NYC public school system.

Courtesy of Fred Smith

A prayer card for the late Wayne Barrett. Illustration by Jeff Danziger.Read more:

2 thoughts on “Opinion: Remembering the Wayne Barrett I Knew”

A terrific tribute and reminiscence of an amazing journalist, now 5 years gone, who was relentless (and impatient) when it came to his pursuit of the truth. Wonderful that you were able to work with and establish a friendship with WB over the years. Thank you, Fred, for sharing your thoughts and impressions of a good man and a talent taken much too soon.

Thank you Fred Smith for this wonderful tribute to your dear friend Wayne Barrett. I had the privilege of overlapping with Wayne for a short time at the Village Voice, where he generously gave me reporting tips for the investigative features I was writing. One of my fondest memories of Wayne is his delightful habit of calling out to me from his second-floor Windsor Terrace office as I walked my daughter to her nearby elementary school.