Meet activists from across the five boroughs, from oyster keepers in The Bronx to environmental justice advocates in Brooklyn, interviewed by student reporters enrolled in the City Limits Accountability Reporting Initiative for Youth.

Courtesy City Island Oyster Reef

Workers with the City Island Oyster Reef in The Bronx.During the last two years, New York City has seen its fair share of changes and challenges: It was the epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic, spent several days under a mayoral-imposed curfew following civil rights protests last summer and endured unprecedented rainfall this September that flooded streets and subways, killing more than a dozen residents.

At the same time, countless New Yorkers stepped up, as they always do, amidst these and other crises to aid one another, press for neighborhood changes and make their voices heard. Below, you’ll find interviews with just a few of these community activists, from oyster keepers in The Bronx to land use advocates in Brooklyn.

These profiles were produced by student reporters enrolled in the City Limits Accountability Reporting Initiative for Youth (CLARIFY), a paid internship program we’ve operated since 2014, which teaches and trains the next generation of New York City journalists. Liz Donovan, who covers climate change and the environment for City Limits, oversaw their work.

All Ages Bond Over Oysters in The Bronx

Courtesy City Island Oyster Reef

City Island Oyster Reef workers.By Khushba Ahmed, Filomena Baker, Fatoumata Doumbouya and Jeshua Guerrero Lopez

Barbara Zahm has been committed to activism for nearly six decades — a dedication that even once landed her in jail. But now as treasurer of a groundbreaking restoration project on City Island, the world remains her oyster.

Two years ago, Zahm joined the City Island Oyster Reef project, an effort to restore the oyster reef just off of City Island, which once had a vibrant oyster economy. This time, however, the oysters would not be for eating; rather, they’ll serve as a way to provide natural water filtration and protect the island from storm surges and flooding, which frequently plague the community.

“We’ve discussed a lot about how important the reintroduction of oysters back into our waters is, and how that could really help City Island overall,” Zahm told City Limits.

Zahm, who describes herself as a “senior activist” originally found her calling in social justice as a college student in the 1960s protesting the Vietnam War and working in the Free Speech Movement.

As a student at University of California-Berkeley, Zahm was horrified to hear about the human rights violations during the Vietnam War. While some of her friends were drafted into the military, she became part of the resistance.

“I couldn’t go on with my own life until the war ended,” she said.

As a part of the G.I movement, Zahm participated in protests and organized around military bases, asking veterans to share their experiences. After college, she produced two documentaries: “Bombs Will Make the Rainbows Break,” portraying the fear of nuclear war that Americans felt in the 1980s, and “The Last Graduation,” chronicling the education system in prisons and how many such programs were eventually wiped out following the Crime Bill in the 1990s.

She later worked as the head of a department of writers publishing curriculum materials developed by leading educators with funding from the National Science Foundation. The goal was to engage middle and high schoolers in social justice issues and empower them in math and science.

“We didn’t change the world, but we changed people’s lives. I know that,” Zahm said.

After 30 years of impacting students and raising awareness on social issues, Zahm realized that though she lived for years on City Island, she hadn’t given the same attention to her home.

Her new “think globally, act locally” focus coincided with the initiation of the City Island Oyster Reef project. She immediately became involved.

Because of her background in education, she knew how vital it would be to get children to care about local issues. For the past two years, she’s worked to secure grants to hold educational events for the community, including the popular Viva La Sound Festival, and collaborating with local educators.

Karen Heil, a middle school science teacher at the local school, P.S 175, has worked closely with Zahm and the City Island Oyster Reef to engage students in their classes and community, incorporating it into the curriculum and even participating in hands-on work on the project.

Zahm’s fundraising skills also acquired $270,000 from the Fish and Wildlife Foundation for the group, funding that allows the volunteers to investigate, plan and create two oyster reefs in the waters just off the island. She has also collaborated with other local organizations, including the Long Island Sound Future Fund. “They think we’re one of the hottest grassroots groups going,” said Zahm.

That collaborative spirit has allowed the group to flourish into an intergenerational non-partisan organization, bringing people together under the shared goal of caring for their community and its future, Zahm said.

Many members are retired, putting everything they’ve learned in life into teaching the next generation how to care for their community above all else.

“I think City Island is divided right now the way the country is divided,” Zahm said. “The thing I like about the City Island Oyster Reef group is that I can bring in diverse people. In other words, it’s not political in the sense that it’s left or right. It’s [the] environment. It’s everyone’s interest.”

Chelsea Community Fridge Provides Discreet Solution to Food Insecurity

By Amanda Chen, Rosalie Flores, Michelle Grullon, and Lina Lin

Courtesty Lea Rose

The communal fridge in Chelsea.As the COVID-19 pandemic dismantled many aspects of life, low-income New Yorkers experienced a crisis that’s only continued over the past two years—food insecurity and food waste.

Around 1.5 million city residents struggle with being able to purchase enough food or being able to afford healthy food plans, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Chelsea resident Lea Rose saw her neighbors struggling with food insecurity, and decided to do something about it.

“There’s food for everyone, but it’s not going into the hands of the people who need it,” said Rose. During the pandemic, she became part of one of the city’s growing community-driven solutions to food scarcity—the community food fridge.

In September 2020, she founded the Chelsea Community Fridge & Cupboard, after personally witnessing people in her Manhattan community struggling to secure basic necessities. Having also experienced hardship herself after losing her job working in the wholesale department of a coffee roaster, she was motivated to find a solution for the lack of affordable food options in Union Square.

Starting out small, Rose reached out over social media to find food donors, monetary donations and volunteers. The post had an immediate impact in attracting donations from food vendors. “Social media has been a huge [tool] for that because as we got more donors, then other bakeries saw the post [and wanted] to donate,” she said.

A year ago, Rose had more volunteers than food donations, but the growing popularity of the fridge has since reached local businesses. “Now it’s the opposite, we have tons of food coming in but not enough volunteers to get it,” she said.

She’s also been able to witness how the project’s growth has directly led to positive financial and health impacts in her community. “Someone told me, ‘It was because of this organization that I was able to buy a birthday gift for my daughter,’” she said.

The take-what-you-need policy allows people to get access to food with dignity in a discreet way. “There aren’t enough places where people can get food without stigma,” Rose said, adding that some places require people to show a pay stub to prove that they can’t afford the items. “There’s also the shame that people have from standing in line at a food bank.”

Rose herself had to rethink her misconceptions about food scarcity. She recalls once seeing a single person emptying an entire fridge. Initially frustrated about having to reload a newly filled fridge, she recognized that she did not know this person’s home situation.

“They could be taking food for their family, for their neighbors,” she realized. That moment inspired her to teach the community how to have genuine trust in one another.

“I think there’s still some shame in coming to a community fridge but at least no one has to prove [their needs] to anyone,” she said. “As long as the food gets eaten, it really doesn’t matter to us who gets it.”

Passing the Torch in Nature Preservation

By Grace Adesanya, Josette Lombardi, Luke Macwan, and Sierra Williams

Courtesy John Garcia

A map at Staten Island’s Serpentine Art and Nature Commons (SANC)Imagine hiking through natural, wooded hillsides with native trees and plants, as hawks soar in the clear blue sky above. Imagine glacial sinkholes and wildlife full of rarely seen ecosystems, and animals such as opossums, raccoons, squirrels, rabbits, and a variety of birds in the underbrush. Imagine green milkweed and slender knotweed hugging your feet, as you pass through serpentine barrens.

John Garcia doesn’t have to imagine — for him, this scene is his typical workday.

As the president of the Serpentine Art and Nature Commons (SANC), he devotes his time to maintaining 40 acres of land in a public nature preserve of Staten Island.

A major focus for him is motivating the next generation of volunteers to care for their local environmental sites. Through SANC’s youth programs, he’s hoping to inspire a new cohort of stewards to continue his work—which he says is at risk of falling victim to industrialization and gentrification.

“I’m very fearful of what would happen to Serpentine if I were to sell it or leave,” he said.

The commons, a non-profit local community-based and -focused organization, was founded in 1978. In addition to stewarding the preserve, complete with hiking trails and biodiversity, the organization offers field trips for local schools and a summer program through which young New Yorkers explore their passion for nature while volunteering on the grounds.

Garcia has a personal connection with the youth program—as a child, the native New Yorker participated in it himself, which allowed him to immerse himself in his community and its natural environment.

He used to work as a police officer in lower Manhattan but was struck by a car. Volunteering, he said, remains his civic duty.

Now he transmits this energy into helping nature survive and thrive. And by working with a new batch of young, bright volunteers—with COVID-19 precautions in place —he is hopeful that he can inspire the next generation.

He teaches them the importance of protecting and maintaining the nature preserves. Garcia believes that nature, with local and public accessibility, truly benefits its community’s inhabitants and the beauty of an area: “There’s positive things about preserving the land,” he says.

Right now, his attention is focused on warding off realtors and corporations who want to build on the park, through legal measures when necessary. For example, he’s currently fighting against the potential development of a BJ’s Wholesale Club and gas station on the Graniteville wetlands.

“Real estate guys, all they want [is] to come and destroy, build, develop and run,” he said. “They make their money, they’re gone and then you have to deal with it.”

That’s why he believes it is paramount to be involved from a young age—to be active and give back to the community.

“Children are the future,” he said. “You guys are the future.”

Leading by Example in Queens

By Ankita Das, Natalia Lashley, Samama Moontaha, and Erica Yang

Courtesy Jaslin Kaur

Jaslin Kaur, above, spoke to CLARIFY reporters about her work aiding Hurricane Ida victims and advocating for the city’s taxi drivers.For Jaslin Kaur, the climate crisis hits close to home—literally.

When the remnants of Hurricane Ida caused deadly flash floods in Queens, the former City Council candidate was devastated to learn that she lived only 10 minutes away from two of the victims.

On Sept. 1, 43-year-old Premattie “Tara” Ramskiret and her 22-year-old son Nicholas “Nick” Ramskiret—both immigrants from the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago—died when floodwaters poured into their 183rd Street basement apartment in Hollis. They were two of 13 New York City residents who lost their lives in the floods, many of them tenants of basement apartments.

The incident is one that Kaur had worked to prevent previously, after listening to Black, Guyanese, and Bangladeshi residents voicing their concerns about flood safety.

“[When] I was running for Council, I really prioritized legalizing basement apartments and protecting tenants, and I got a lot of backlash for that,” she told City Limits.

After the floods, Kaur and a colleague visited the homes of people whose apartments had been affected and helped to clean up. She was also able to restore some of the personal items that had been damaged.

“It was very hard to experience that firsthand, but it jolted a wake-up call,” she said.

Kaur, who was born and raised in eastern Queens’ District 23, is the daughter of Punjabi immigrants. Her background inspires her to focus on issues that affect working-class immigrants—particularly how they’re affected by economic and environmental inequities.

Her father, Partap Singh, joined thousands of other taxi-cab drivers as they struggled to pay back hundreds of thousands of loans amidst the taxi medallion market crash of 2014, which left drivers across the city trapped in a daunting cycle of accruing debt.

Kaur was with her father when he celebrated alongside 25,000 other cab drivers as they declared victory on Nov.12. After two months of protest and a two-week hunger strike, the New York Taxi Workers Alliance won a historic victory that will provide a $65 million relief program for struggling medallion owners, potentially unshackling thousands of drivers from predatory debt.

In her run for Council District 23, Kaur was been endorsed by the New York City Democratic Socialists of America, the Working Families Party, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s Courage to Change Political Action Committee, among others. Still, she lost the June primary election to rival candidate Linda Lee.

Kaur said she is continuing to focus on better access to transportation in the outer boroughs and on environmental justice, both issues which she notes disproportionately affect communities of color.

“It’s a pattern of exploitation across our city,” she said. “[It’s] a history of working people, of immigrants, who had just not been able to achieve the kind of dignity that they deserved and that they were promised when they came to this city and to this country.”

Sunset Park Youth Organizers Rise Up

By Cynthia Leung, Hazel Melendez, Marie Pontius, and John Powers

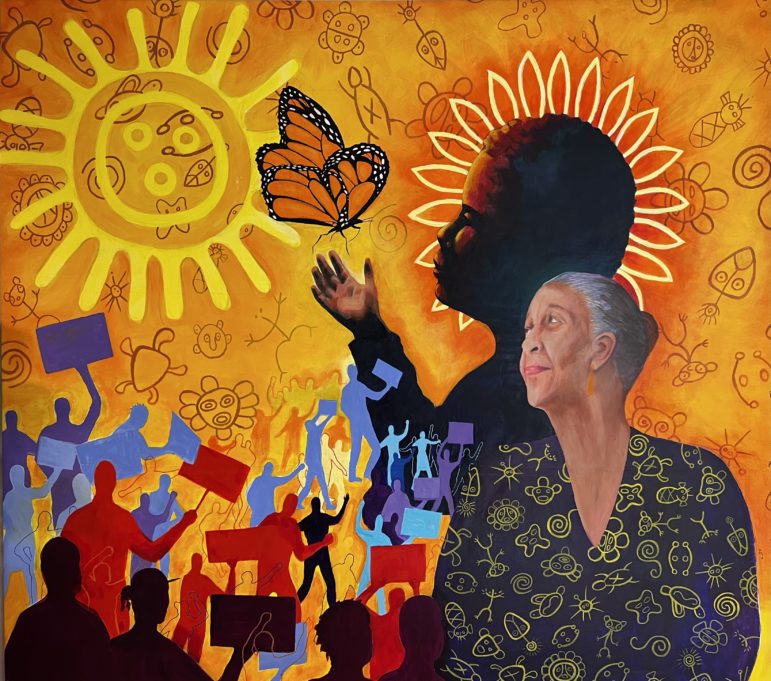

Maria Dominguez, courtesy of UPROSE

An UPROSE mural.Sunset Park, once a thriving waterfront community, has become plagued with highways, industrial parks and toxic chemical storage, making the neighborhood a microcosm of the global climate crisis. But it’s now being fiercely protected by an intergenerational community group of environmental justice-focused organizers, called UPROSE.

In the 1950s, the neighborhood was sliced by the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway, where tens of thousands of trucks and cars, many of them commuters from outside the community, pass through every day. Its maritime area holds oil storage facilities of toxic chemicals and vacant lots with pollutants trapped under the asphalt.

As a result, residents of Sunset Park, predominantly people of color, have long suffered the health consequences, including asthma and other respiratory ailments.

That’s why UPROSE organizers have focused their attention on promoting clean energy and climate justice through legislation, education, art and direct community action.

But most notable is the group’s focus on amplifying the voices and organizing efforts of its youth volunteers—resulting in a “continuum of leadership” that founder Elizabeth Yeampierre said is important to its mission.

“One of the things that I love about UPROSE is that on our staff and on our board are young people growing up in the organization,” Yeampierre said. “That intergenerational part of our cultural practices, you’ll see it show up in the kinds of events that we hold and who facilitates them and how the issues are framed.”

Nyeisha Mallet, a student at Cooper Union, joined the organization six years ago—the position was her first job. Her most memorable campaign was being involved with the fight against Industry City, the complex of old factories turned into a commercial space which its owners sought to expand through a rezoning last year.

Concerned that Industry City would gentrify Sunset Park in a way similar to Williamsburg and take away valuable resources for green industrialization, Mallett took part in organizing to voice concerns over the development.

UPROSE organizers provided testimony and brought together scientists, lawyers, and community members to form a coherent message against the proposal, which was eventually dropped by the site’s owners. This approach represents the group’s hands-on, education-focused approach to influencing change—that is, teaching the public about issues affecting the community as well as inspiring the next generation of organizers.

“Direct action is important, disrupting is important because that’s how we get attention,” said Mallet, “but community-building is the seed to everything else.”

Mallet works with Isabella Correa, a high school junior who joined UPROSE only a year ago but shares her colleague’s passion for community advocacy through intergenerational collaboration.

Correa has attended many climate protests throughout her life, but her involvement with UPROSE felt like a unique opportunity to pursue a just transition where both racial and climate justice are achieved.

“I’m here to learn, and it doesn’t stop once the march is over,” said Correa.

“If we’re not solving the problem, then these rich white corporations [are] going to do it for us and not in the way that we want or not in the way that we need.”