“The solution to homelessness is housing,” one stakeholder said. “But the city agency charged with solving homelessness has no jurisdiction over housing, so we are setting them an impossible task.”

David Brand

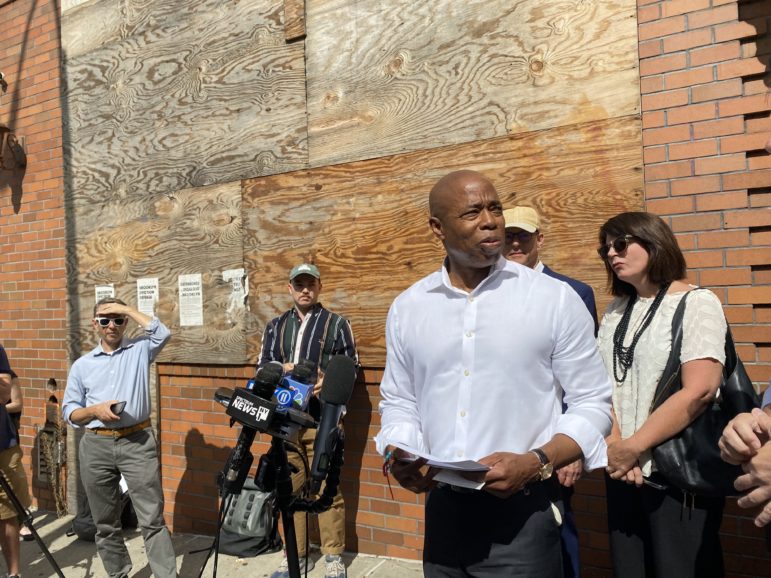

Eric Adams announced his plan to convert struggling hotels into homeless housing in September.As Mayor-elect Eric Adams prepares to tackle New York City’s ongoing homelessness crisis, influential advocates and institutional heads are urging him to improve coordination between housing and service agencies to accelerate moves into permanent homes. They’re also recommending he create a brand new position with a singular mission: end homelessness.

Under the city’s current structure, one deputy mayor oversees the Department of Homeless Services (DHS) and the Human Resources Administration (HRA)—merged since 2016 in the Department of Social Services (DSS)—while another oversees NYCHA and the Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD). DSS and HPD use different digital systems, and the city is still building out a database of shelter residents’ housing needs, incomes and potential eligibility for rental subsidies.

The arrangement contributes to a disconnect between the agencies tasked with managing and reducing homelessness and the ones that oversee actual affordable homes, said Christine Quinn, CEO of the family shelter and supportive housing provider Win.

“We cannot have the silos that we have had,” Quinn said. “It’s incredibly ineffective. We need the buck to stop with one person and that person needs to report directly to the mayor.”

Quinn has advised Adams to put someone “in charge of all aspects of homelessness,” including housing, to fuel collaboration across agencies and link people in need of housing with available apartments. She proposed the new role as part of a five-point policy plan for tackling homelessness in the first 100 days of the Adams Administration. Her other recommendations include appointing New Yorkers who have experienced homelessness to his administration, and creating a citywide agenda for ending homelessness that incorporates every relevant agency.

The former City Council speaker also encouraged Adams to invest $2.35 billion into new affordable housing development while building at least 8,000 units a year for extremely low-income renters and setting aside 3,000 apartments a year for homeless New Yorkers.

Adams has set a target of 25,000 new supportive and affordable apartments inside converted hotels, an ambitious undertaking that will require coordination across city government and the nonprofit sector. About 16,000 people have moved into supportive housing since Mayor Bill de Blasio took office in 2014, but thousands are still waiting for a limited number of units.

DSS Commissioner Steve Banks’ recent decision to take a job in the private sector ended speculation that he would continue to serve under Adams, and fueled rumors about who might take over the social services agency—or what the bureaucratic structure will look like in a month. Adams could decide to split HRA and DHS under separate commissioners or, as many advocates hope, restructure various agencies under one authority figure.

If Quinn had her way, the official tasked with ending homelessness would be someone “who has a lot of experience and who has worked both inside and outside of government on issues of homelessness.”

That sounds a lot like Quinn herself. She declined to say who she had in mind for the position, but she didn’t rule out taking the potential role if Adams asked.

“I learned a long time ago not to opine on jobs you are not offered,” she said. “I am very grateful to have the position I have now and my goal has always been to serve the people of New York City.”

Adams’ transition team did not answer questions about how he might approach the city’s response to homelessness or who he might hire to lead that response—either in the current structure or in a new position, like deputy mayor.

His ultimate leadership decisions will have a huge impact on tens of thousands of New Yorkers. There were 45,833 people, including nearly 8,500 families with children, staying in a DHS shelter Monday night, according to the city’s most recent daily census. The end of state eviction protections next month will put tens of thousands of others at risk of losing their homes.

Quinn isn’t the only one who thinks Adams needs to appoint someone to increase coordination between the housing and social service sectors. A coalition of nonprofits, including VOCAL-New York and Association for Neighborhood and Housing Development, published a report in February urging the next mayor to tap a deputy to oversee a proposed Integrated Housing Plan. The plan would incorporate all agencies “involved in housing, building and planning to create one coordinated strategy focused on ending homelessness and promoting racial equity.”

“DHS, NYCHA, and HPD must all have shared metrics for providing housing for the homeless,” they wrote in their “Right to a Roof” report, adding that the Department of City Planning “must in turn ensure that planning decisions further these goals, and [the Department of Buildings] must prioritize approvals for related construction projects.”

Another coalition, the United For Housing Campaign, proposed a deputy mayor position as part of its policy platform for the next mayor in 2020.

“We think that the next administration has to have a greater recognition that housing is the answer to homelessness,” said Coalition for the Homeless Policy Director Jacquelyn Simone, whose organization worked with the group on their recommendations. “While changing the administrative structure for these policies won’t be the only solution for ending mass homelessness, it’s an important first step in better aligning homelessness and housing policies.”

Simone highlighted the city’s successful interventions for preventing more New Yorkers from becoming homeless, including a right to an attorney in housing court for low-income tenants facing eviction and the expansion of rental assistance grants—initiatives implemented by Banks and the revamped DSS Mayor Bill de Blasio decided to merge HRA and DHS into DSS in 2016 to coordinate homeless prevention and homeless services—a potential model for fostering collaboration with housing agencies.

The prevention strategies have earned considerable praise, though leaders say they could go even further.

Richard Buery, head of the Robin Hood Foundation and a former deputy mayor, told City Limits that Adams should increase income thresholds for those prevention strategies as eviction protections approach a Jan. 15 end date.

And Áine Duggan, president and CEO of the Partnership for the Homeless, encouraged the next mayor and City Council to streamline the rental assistance application process and increase set-asides for homeless New Yorkers from 15 percent of city-funded apartments to 25 percent.

“The solution to homelessness is housing,” Duggan said. “But the city agency charged with solving homelessness has no jurisdiction over housing, so we are setting them an impossible task.”

The Safety Net Project of the Urban Justice Center and #HomelessCantStayHome Campaign issued an even more ambitious demand, encouraging the city to house homeless New Yorkers in affordable units administered by HPD, regardless of the current income thresholds for the apartments. “While HPD has made some units available to homeless New Yorkers in recent years, the number remains extremely low relative to the City’s homelessness crisis,” they wrote in their demand.

Adams seems to agree with that idea. During a video interview with City Limits earlier this year, he said he would tackle homelessness by filling affordable housing vacancies and using subsidies to help homeless New Yorkers move into empty HPD units reserved for moderate income renters.

“Why do we have so many units that are vacant when we can place people into housing in those units, and it would actually be cheaper?” he said. “My focus is going to be on housing. Getting people out of shelter and moving them into permanent housing.”

Many of the demands for a deputy mayor or housing and homelessness czar reflect a desire for Adams to explicitly prioritize ending homelessness and invigorating municipal agencies to act on that mission.

Shams DaBaron, an advocate and former shelter resident known as Da Homeless Hero, urged Adams “to bring in someone who can reorganize DSS and who is committed to eliminating the bureaucracy and finding ways to address housing.”

“But we have to be careful because a lot of the problems we saw in this administration were at the direction of the mayor,” he added.

That’s a concern shared by Erin Kelly, a former DHS consultant who now runs the homeless advocacy organization RxHome. A commitment to ending rather than managing the crisis begins at the top, she said. Merely appointing a deputy mayor to oversee the housing and homeless service agencies could just be “checking a box” if the administration doesn’t foster true system-wide coordination, she added.

“There’s a lack of collaboration between agencies both in terms of working to help specific New Yorkers in need,” Kelly said. “And at a high level, the strategic missions or planning for those agencies happen in their own vacuums.”

That commitment also means reckoning with the true extent of the homelessness crisis, say multiple advocates.

The number of people staying in DHS shelters has become shorthand for the city’s total homeless population, in large part because that number is easily accessible through daily census reports mandated by local law. But that reporting does not include thousands of other New Yorkers in separate municipal shelter systems, including 1,126 single adults in SafeHaven beds for people coming from the streets and public spaces, as well as thousands staying in youth shelters contracting with the Department of Youth and Community Services, families in domestic violence shelters overseen by HRA or New Yorkers in emergency shelters run by HPD.

Mayor Bill de Blasio’s administration has resisted reporting on the total number of people in municipal shelters because other administrations were not bound by that requirement and the new tally would show a higher number. A true reflection of the number of New Yorkers using municipal shelters would not be an “apples to apples” comparison to the DHS shelter population reported by past administrations, Banks said at a City Council hearing this year.

Nicole Branca, the head of supportive housing provider New Destiny Housing and a former deputy director at the Supportive Housing Network of New York, said Adams could immediately change that.

“Right out of the gate, and what other mayors haven’t done, is create one homelessness census,” Branca said. “Without that constant attention, the lion’s share of resources, accountability all fall to the DHS system and the others eventually end up in the DHS system.”

She also suggested that Adams seek out feedback from the very New Yorkers experiencing homelessness, as well as the people doing the work at all levels of city government to highlight gaps and problems.

“Rather than put out a big glossy report and hiring consultants on how to end homelessness, he should put working groups together of the people in the agencies doing the work, people in communities and people with lived experience,” Branca said. “Have them identify for City Hall where the roadblocks, which agencies have the slowest inspections, which agencies take three months to fill a vacancy.”

“Apartments stay vacant for a very long time,” she added. “That could be a game-changer if we speed that up.”

2 thoughts on “Advocates’ Advice for Eric Adams? Better Coordination Between NYC’s Housing and Homelessness Agencies”

Wow, all the poverty out.ps making hundreds of thousands a year exploiting the homeless all want more spent. Who would have seen that coming?

Why? Haven’t the Mayor Adams followed up on the homeless people he had taken off the streets the shelter on 127W.25 the Street 7 the ave has been resented that shelter is unsanitary and rat rodens in the clients rooms and the staff does nothing but sit there the foundation whom runs that faculty need to be questioned be ause of the conditions seen. Now Mr. Mayor Adams so caring why? Haven’t this people have gotten the assistance they need the help of living permanent housing they are it getting any assistance from your office and are being treated unfairly accordingly I’ve seen now I’ve been in a shelter and had to fight and retract my findings to get out but the disabled people aren’t getting that treatment and being untreated so why why why you Mayor Adams aren’t helping