The city’s sprawling, patchwork supportive housing network is designed to provide homes and services for people who have experienced homelessness. But too often the model leads to unnecessary restrictions, inconsistencies and even glaring housing violations against vulnerable residents, according to the people who live there.

David Brand

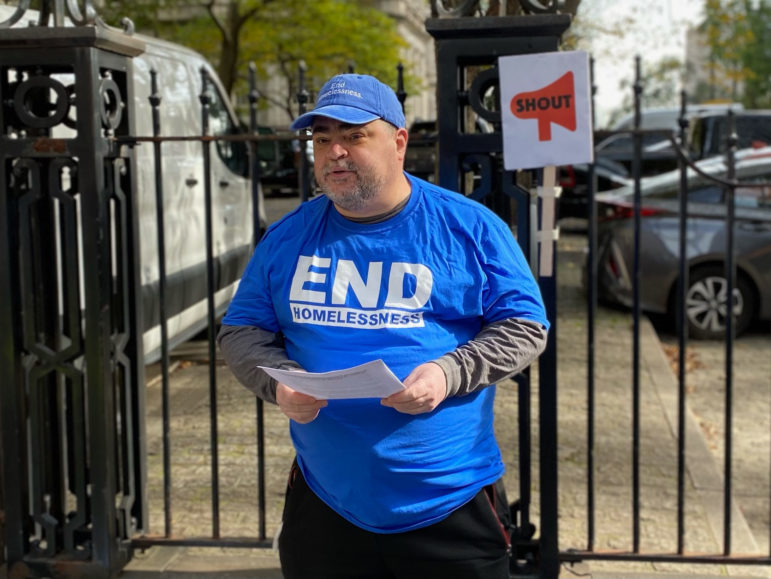

Mike Anderson, an organizer with the Supportive Housing Organized and United Tenants (SHOUT).New York City’s sprawling supportive housing network is managed by scores of nonprofits and funded by dozens of city, state and federal programs, all part of a system designed to provide homes and services for people who have experienced homelessness. But too often the model leads to unnecessary restrictions, inconsistencies and even glaring housing violations against vulnerable New Yorkers, according to the people who live there.

That’s why some of them have begun organizing.

A group of residents from Brooklyn, Manhattan and the Bronx united in April to form what they say is the first citywide supportive housing tenants union. For the past six months, Supportive Housing Organized and United Tenants (SHOUT) has met weekly over Zoom to strategize around policy, discuss the problems they face and learn more about their housing rights with the assistance of attorneys and advocates.

On Thursday, SHOUT will hold its first rally and press conference outside City Hall to back legislation that would compel supportive housing organizations to issue a bill of rights to all tenants.

The measure, Intro. 2176, would require the Department of Social Services to provide a written notice of tenants’ rights under state and local housing laws to every supportive housing tenant at move-in, lease renewal or upon request. It’s a straightforward but important step, said SHOUT organizer Xena Grandichelli.

“It lets people know, if you’re in supportive housing, these are your rights. It’s the rights that any other tenant in any other apartment building is afforded,” Grandichelli said. “It’s so we can bring legitimate complaints and we have a legal leg to stand on.”

Grandichelli cited her experiences at a Bronx supportive housing site, where she said staff enter units without providing notice and where broken elevators can complicate life for tenants. The provider, the Jewish Board, did not respond to requests for comment.

SHOUT has ramped up its advocacy as a new set of leaders prepare to take office, with many, including Mayor-elect Eric Adams, calling for an expansion of supportive housing in unused hotels and commercial buildings.

‘Not in a safe situation’

New York City’s first supportive housing apartments for people with mental illness opened inside single-room occupancy buildings (SROS) in the 1980s, fostering a supportive housing boom in the 1990s. The five boroughs are now home to 35,000 supportive housing units, according to the Supportive Housing Network of New York trade group, and more are in the pipeline.

Adams has made supportive housing a key feature of his plan to tackle chronic homelessness. He pledged in September to create another 25,000 apartments under the model, which includes apartment buildings run by nonprofits with on-site social services for formerly homeless New Yorkers, as well as about 16,000 “scattered-site” units located in privately owned properties where case managers and social workers make routine visits. In both cases, rents are typically covered through a mix of housing subsidies—with funding available specifically for people with mental illness or HIV/AIDS—and a portion of the tenant’s income.

But the various funding requirements, financial constraints and the number of parties involved can lead to restrictions for tenants. SHOUT members who spoke with City Limits in recent weeks described a one-size-fits-all approach for residents, regardless of their needs; pressure to transfer from one scattered-site unit to another, often with roommates and in unfamiliar neighborhoods; paternalistic policies for limiting overnight visits or collecting money for rent; restrictions that can make it hard to enter their homes; and a general lack of transparency.

“I got involved with the group because I don’t have a rent receipt, I don’t have a copy of the house rules,” said SHOUT organizer Tracy Nuzzo.

Nuzzo said she didn’t get a front door key for months after moving into a supportive housing site on the Upper West Side and that she had to wait for front desk staff members to let her in—a particular problem when the workers went on break.

Bay Ridge resident Michael Korn, another SHOUT organizer, subleases a studio apartment in a private building rented by the Institute for Community Living (ICL)—one of roughly 16,000 scattered-site supportive housing units in New York City—but said he was pressured last year to move into a shared apartment in Crown Heights with a person who smokes.

Korn, who has bipolar disorder and has experienced homelessness, said he found stability in his current Bay Ridge apartment after he arrived there in 2014. He didn’t want to abruptly move in with a stranger, especially a smoker who could affect his existing respiratory problems. He decided to decline the move and contacted an attorney from the organization Mobilization for Justice. His resistance helped lay the groundwork for SHOUT.

“I’m not in a safe situation and neither is anybody else who can just be given an ‘I’m sorry, we changed the rules, you gotta move tomorrow,’” he said. “I don’t want to move. Why should I have to move? I think I should have a right to stay.”

Korn said a caseworker informed him that the agency was a eliminating single-person apartments in its scattered-site supportive housing program and that he had to leave. Korn said he did not know he had a right to remain in place until reaching out to an attorney who said he could challenge the move. An ICL spokesperson said the agency continues to sublease single apartments for scattered-site supportive housing tenants.

David Brand

Supportive Housing Organized and United Tenants (SHOUT) members at a press conference at City Hall Thursday.An important first step

“One of the most frustrating things we hear from tenants in supportive housing is that they do not receive information, or are given misinformation, about their essential tenants’ rights by landlords and service providers,” said Jenny Akchin, a staff attorney with TakeRoot Justice who has advised SHOUT. “You can’t exercise housing rights you don’t know you have, so this bill is a really important first step towards ensuring that supportive housing tenants can self-advocate for improved housing conditions.”

Brooklyn Councilmember Stephen Levin, the Intro. 2176 sponsor, has participated in regular conferences with SHOUT members, advocates and providers, and said the bill of rights will foster respect and transparency among all parties.

“The vast majority of supportive housing providers and staff are really compassionate and hardworking people and really dedicated to the work they do and doing a lot of hours for not a lot of pay,” Levin said. “But I think [the legislation] is in everyone’s interest because the most successful arrangements are built on mutual respect for each other’s rights.”

“These rights are through state legislation, housing law and any rights they have gained through litigation,” he added. “This is just making sure tenants know all of them.”

Funding rules attached to supportive housing usually require staff to meet with tenants a certain number of times per month and complete service plans and other documents that benefit many, but not all, tenants. Some units are funded by the state’s Office of Mental Health, others through the city’s Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, and still more through the city’s Continuum of Care—among the 86 funding streams listed on the Supportive Housing Network guide for providers.

“There is a crazy quilt of funding arrangements behind supportive housing, and as a result there are many different sets of rules that might apply to supportive housing tenants depending on how their site was developed,” said Legal Aid Staff Attorney Joshua Goldfein. “This makes it very difficult for tenants to understand what their rights are, and that’s why it is so important for the city and providers to give them this information when they renew their leases.”

Key parties have agreed to support the bill, while also highlighting the hard work of nonprofit supportive housing organizations that provide the apartments, as well as staff members who offer social support, mental health treatment and case management for formerly homeless New Yorkers.

“We are pleased to have worked with the City Council to develop a strong supportive housing bill of rights to ensure tenants have complete information about their residence and easy access to facts about their rights as tenants of supportive housing,” said the Supportive Housing Network of New York in a statement.

The legislation is delayed amid internal negotiations over the final text, but has also earned the support of Mayor Bill de Blasio and his administration.

“All residents of supportive housing deserve to know their rights and we’re proud to support this bill,” said a City Hall spokesperson.

But with just two months left in the current administration and City Council, SHOUT members say they are just getting started. They’ve set their sights on another piece of legislation that would require the city to report annually on the number of supportive housing applicants, move-ins and rejections. The measure would also compel providers to describe the reasons for those rejections.

They’re planning to take their advocacy to the Adams administration.

“Everything is good until it’s not,” said Korn, the Bay Ridge resident. “You have to keep advocating for yourself.”

This story has been updated to clarify Korn’s experience at his Bay Ridge apartment.

2 thoughts on “Pioneering Tenant Group Champions Rights of NYC’s 35K Supportive Housing Residents”

I help to start a tenant association in this support housing. We would like your help or any information you can help with . We are located at

249 Classon

If u r in supportive housing, access greater help thru SHOUTNYC.ORG.