Health advocates point to a spike in overdose and opioid deaths during the pandemic, saying the pilot program to launch five Overdose Prevention Centers—four of them in the city, where people can use drugs under supervision would save lives—would save lives.

NYAG

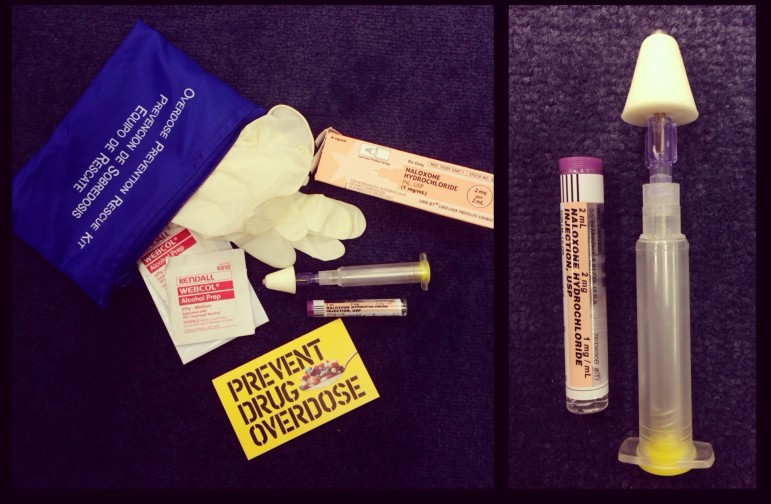

A Naloxone overdose prevention kit.Three years ago, when then-Governor Andrew Cuomo was running for re-election, health advocates say he promised them he would move forward on a pilot program to launch the state’s first Overdose Prevention Centers—designated sites where people can use intravenous drugs under supervision, a harm-reduction model that supporters say helps prevent overdose deaths.

READ MORE: Amid Debate Over Designated Injection Sites, Dwindling ‘Safe’ Options for NYC’s Opioid Users

But the initiative never came to pass, says Charles King, chief executive for the nonprofit Housing Works, which has been pushing for the implementation of the centers—also known as safe injection sites—for the last several years.

“All of sudden, all the conversation stopped,” King said of Cuomo, who resigned this week in the wake of sexual harassment accusations. “We very much feel that we were lied to by the governor and that he probably had no intention of keeping his word.”

In the years since that deal fell through, the opioid crisis in New York and nationwide has showed no signs of slowing. The U.S. saw a nearly 30 percent increase in drug overdose deaths in 2020 compared to the year before, and New York State saw 5,112 people die from overdoses last year, 2,192 of them in New York City, according to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data.

Overdose deaths across the state rose by nearly 37 percent in 2020 compared to 2019, the numbers show. “With the pandemic, people are more isolated,” said King. “More people are using opioids alone in high-risk situations.”

Now, he and other advocates are turning to new Governor Kathy Hochul to deliver the Overdose Prevention Centers they say Cuomo reneged on. On Tuesday, as Hochul was being sworn in as the first female governor of the state, Housing Works and more than 60 other New York community-based organizations and advocacy groups sent her a letter imploring her to take up the cause.

“One of the things she seems to be committed to doing is cleaning up some of the mess that Governor Cuomo left behind,” King said. “We consider this to be part of that mess.”

Hochul’s office did not comment directly about the new administration’s stance on safe injection sites; a spokesperson told City Limits the state’s new leader is “looking forward to tackling issues facing New Yorkers head on.”

“The input of impacted groups is appreciated as she evaluates how best to create a stronger future for all,” Hochul’s spokesperson added.

In her former role as lieutenant governor, Hochul co-chaired the state’s Heroin and Opioid Task Force, which produced a report of recommendations in 2016 that King says “was a lot about Narcan access, nothing else really harm reduction-oriented.” Hochul also hails from Erie County, he notes, which experienced a 57 percent uptick in opioid-overdose deaths last year.

“I think she’s certainly sensitive to the overdose crisis. Whether that means that she’s willing to step out and do something like this, I don’t know,” King said.

Advocates are specifically asking Hochul and the state Health Department to allow five existing Syringe Exchange Programs, four in New York City and another in Ithaca, to expand their services to include “supervised drug consumption.” Supporters say such Overdose Prevention Centers allow people who are going to use drugs regardless to do so in a safe and clean environment; The centers do not supply the drugs, just monitor the use of them, with medical staff on-site to treat people for overdoses should they occur.

King says the centers provide other services, like the ability to test batches of drugs for specific quantities of things like fentanyl, a highly potent opioid that’s commonly laced with other street drugs, fueling the overdose crisis. The safe injection sites would also be able to engage with more drug users, many of whom are often cut off from the healthcare system, and open the door for them to things like counseling and addiction treatment.

King compared the centers to syringe exchange programs, which sparked a similar political debate decades ago but are now a well-established tactic used by health departments to prevent the spread of blood-borne diseases like HIV/AIDS and hepatitis.

“They’re getting more than clean syringes. They’re getting support, counseling,” King said. “People had all these objections to syringe exchanges and all of the evils that they would cause.”

There are approximately 120 overdose prevention centers operating worldwide, the advocates say, and a number of jurisdictions in the U.S. have been exploring their use, though actual implementation has been thornier. Lawyers for former President Donald Trump’s administration sued to stop one such program from getting off the ground in Philadelphia, saying it would amount to “normalizing the use of deadly drugs.”

King says the court’s decision in that case would not prohibit New York from pursuing its own pilot, and he and other advocates hope President Joe Biden will be more accepting than the previous administration.

“The issue at hand now is, particularly given how conservative the Supreme Court is, would the Justice Department continue to pursue cases like this?” King said. “We are hoping that we can get the same kind of commitment…that this administration would not pursue cases to block this, but would allow states to experiment.”

Mayor Bill de Blasio supports safe injection sites, and was among several mayors across the country who urged the Justice Department this spring not to block their implementation. Rhode Island’s governor signed legislation last month authorizing that state’s first safe injection site pilot, and lawmakers in Massachusetts are pursuing a similar program.

Supporters in New York are asking Hochul to authorize the Overdose Prevention Centers pilot by Aug. 31, which marks International Overdose Awareness Day. The state could use some of the funding from its recent $230 million opioid settlement with Johnson & Johnson, King argues.

“Help New York State move past the stigma and fear of those in power and provide real, life-saving services to the people we care for who use drugs and deserve to live a full and healthy life,” the advocates wrote.