‘Broad use of PBL/PBA in the city’s schools could jumpstart New York’s post-pandemic educational era away from the drill-and-kill, standardized test-based techniques of the last 20 years, invigorating teachers and students when motivation and a sense of success are so needed.’

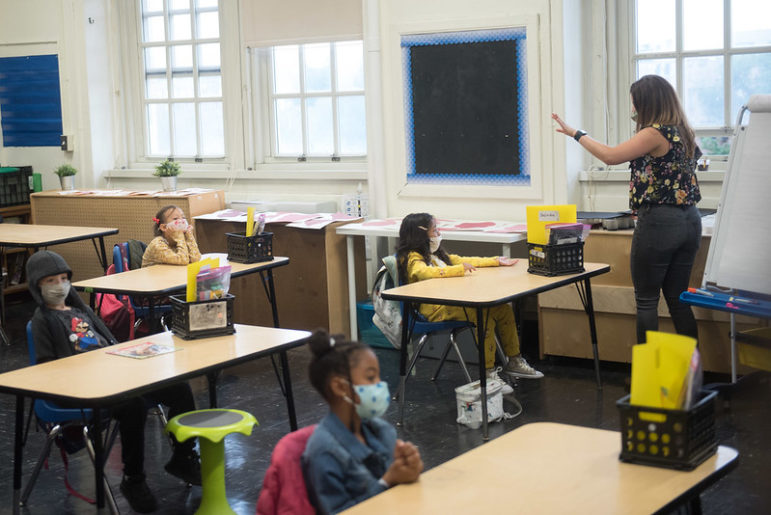

Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office

A scene from the first day of school earlier this year.As an elementary and middle school teacher I fell in love with the demands of project based learning (PBL) after seeing the impact on my students. Instead of studying predigested information, carefully divided by subject with mastery gauged by paper and pencil tests, my students learned by active inquiry, followed by public demonstrations of their knowledge—now called performance based assessments (PBAs).

This was nothing fancy. Individually or in groups, students worked on long term assignments to produce often interdisciplinary work that became deeply personal and could be shared with classmates, the school, parents, and community members including books, quilts, songs, posters, games, storytelling, and other authentic evidence of learning. Today, those projects would be supplemented with videos, websites, and other twenty-first century media. School plays are examples of PBL. So are science fairs.

Plays and fairs, however, are too often exceptional adventures in a student career. On the other hand, PBL/PBA, as a sustained and successful pedagogy, is at the center of the school’s mission. It doesn’t take all of a student’s instructional time, there is still plenty of chalk and talk. But PBL/PBA becomes the rule, not the exception; the design for how teaching is done.

All of this takes lots of work on the teacher’s part. What types of projects fit appropriately with the unit of study? How to make sure no student is assigned more than they can handle but enough so they’re challenged? What technology or other resources might be needed and, if necessary, acquired and funded? If done in groups, how should those be arranged? What information does the teacher need in order to be an adequate but not unilateral resource, allowing student and teacher to discover together, sharing “ah ha!” moments of progress and pride?

CityViews are readers’ opinions, not those of City Limits. Add your voice today!

CityViews are readers’ opinions, not those of City Limits. Add your voice today!

The payoff is in student and family engagement, adaptability for culturally responsive curricula and expression, analytical thinking, increased skill and information retention, and social competencies to name but a few of the impressive outcomes my students experienced. The idea is as old as John Dewey‘s seminal work. But mainstream public education has sidelined his lessons.

These thoughts arise from the New York mayoral campaign. For a group that often promised to “reinvent” education, the candidates proposed a notably familiar set of goals and structures for our schools. Among the goals are universal literacy, racial desegregation, increased numbers of teachers and counselors, fewer cops, and access to high-quality technology. New structures mostly dwelled on academic screening (more, less, or different depending on the candidate), tweaking mayoral control, and a longer school day and year.

The paths to achieve these aims were rarely explained, successful implementation dubious. Besides, these are bureaucratic recommendations, more institutional than educational, the shell not the nut. They have the air of electoral slogans, likely to die on the vine upon taking office. Little is said about actual instruction except that it will be mostly live.

But PBL/PBA provides a real instructional solution hiding in plain sight. A PBL/PBA-based subdistrict, the New York Performance Standards Consortium, has operated in the city’s schools for decades and is recognized by the State Board of Regents as a successful model for achievement and assessment, backed by strong research evidence. Though many of our best schools use the strategy in isolation, it has received scant central attention. By immediately scaling up, we can truly reinvent mainstream public education here and beyond. Broad use of PBL/PBA in the city’s schools could jumpstart New York’s post-pandemic educational era away from the drill-and-kill, standardized test-based techniques of the last 20 years, invigorating teachers and students when motivation and a sense of success are so needed.

As important as its instructional effectiveness, PBL brings a sense of mission to students and teachers that is consistent with any mayoral platform. Through inquiry and revision, students bring projects to life—not bubbling in multiple choice answers that end at the point of a No. 2 pencil. There is nothing about PBL that is watered down or lacking in academic integrity. Learning is active and can be applied to any subject. In the Humanities, Shakespeare leaps from the page to stage. Coding is a perfect example of PBL in the sciences and math, where data entry ends in real world outcomes that become the seeds for future work.

Careers are spawned when learning catches fire in this way. “Soft” skills are a further benefit of PBL instruction. Collaboration is a hallmark of PBL classrooms. Ironically, so is acceptance of failure, since it is seen as a necessary step toward success rather than carrying the shame of being wrong. Thus the goal of “unanxious expectation” coined by educator Ted Sizer is fulfilled, encouraging creativity and experimentation without stigma.

As for marrying the moment to increased use of technology, PBL zooms past the sterility of most remote learning. The internet becomes a true portal for exploration with infinite computational opportunities. School librarians, required by state law but too often relegated to monitoring dust-gathering shelves where schools employ them at all, become key to this endeavor, as research specialists opening up new horizons to faculty and students alike. Similarly, teachers shift beyond their traditional role as fonts of information to resource providers as students, individually and in groups, pursue their projects.

The greatest challenges in scaling up PBL are the leadership and professional development needed to help educators successfully navigate from the routine delivery of a standardized curriculum’s scope and sequence to helping plan and monitor student projects. This presents refreshing clarity for the next Department of Education chancellor search, which can be based on a specific educational vision and relevant experience instead of a generic resume of past district leadership. The good news is that this is well-worn territory with educators here and elsewhere invested in these efforts. No new methodologies need be invented and funding can largely be redirected from less promising current efforts.

The only thing needed now for bringing PBL/PBA practices to the forefront of city schooling is the political will to bring life back to classrooms for children who missed so much pleasure in learning during the past year.

David C. Bloomfield is professor of education leadership, law and policy at Brooklyn College and The CUNY Graduate Center. He is a former elementary and middle school teacher.

2 thoughts on “Opinion: Project-Based Learning Can Jumpstart a New Educational Era for NYC Schools”

I really enjoyed reading this article and could not agree more with your perspectives on project based learning(PBL). My name is Chrissy Rebert, and I am the VP of Global Instructional Solutions at Teq. It is my opinion that project based learning is needed, now more then ever, for students to take ownership over their learning and to have a voice and choice in the way they learn best. With project based learning, students complete a capstone project that showcases their strengths and individualities.

At Teq, we offer iBlocks, instructional blocks, which are project based learning activities that engage students in critical thinking, teamwork, and active learning through the engineering design process. These allow students to take ownership over their learning, offering a robust and creative environment for everyone. With iBlocks, testing, grading, and formal evaluation can be eliminated, and instead, students demonstrate mastery and learning through self-evaluation, discussion, and overall engagement with the project.

When students are actively engaged, learning takes place. Because PBL promotes student-led and teacher-guided, they offer students a place to invent, explore, and practice future-ready skills. Project based learning also allows students to explore career pathways, as they investigate solutions to real world problems.

I am excited to see how districts incorporate PBL into their post-pandemic learning environments. The possibilities are endless. Thanks for bringing awareness to this

holistic, cross-curricular, fun and exploratory way of learning.

– Chrissy Rebert

I’m just now seeing this article and it’s very exciting! I’ve been trying to find more information on NYC schools that teach using PBL techniques but they seem to be all high schools, and mostly private. Are there any public elementary schools in any of the 5 NYC boroughs using PBL?