The measure would have added 41,000 miles of streams to the state’s regulatory system.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

The walleye, one of several varieties of fish that might be pursued in streams that, under current law, are offered less protection than other New York State waterbodies.Citing fiscal constraints, Gov. Andrew Cuomo on Friday vetoed legislation that would have protected fishing streams around the state from activities that can harm wildlife and affect anglers.

A version of the bill in question was introduced in 2018 by Assemblyman Sean Ryan and was taken up in the Senate last year by Sen. Pete Harckham. Both lawmakers are upstate Democrats. It passed the Senate on 2019 but died in the Assembly earlier this year, then was revived to pass the upper body by a 43-17 vote and clear the Assembly by a 113-31 margin.

Waterways in New York State are categorized by their usage, which determine the type of regulations that govern activities on or near them. Drinking waters are labeled AA or A, swimming areas that aren’t used for drinking water get classification B, and waterways that support fishing but not other contact receive a C rating. Other waterways are considered class D.

One wrinkle is the type of fish found in waterways: If an A, B or C waterway hosts trout or trout spawning, it gets a special T designation.

Water with an AA, A or B rating falls under the state’s “protection of waters” regulations, which means that activities that disturb the banks or stream bed or involve dams, docks or the dumping of fill, require a permit. Class C waterways that host trout also fall under those roles.

However, class C waterways that are not home to trout but host other species—bass, walleye, pike, perch and so forth—are not protected, nor are class D. Supporters of the law see that as a problem.

“Class C and D waterways, which are regularly used by people for boating, fishing, and other activities, are not currently afforded the protection that is provided to waterways classified as streams,” Harckham wrote in his sponsor memo. “Because of the close contact people have with class C and D waterways, listing them as streams will allow for their protection.”

The final legislation, however, only applied to class C streams without a trout designation, not class D. That still would have placed 41,000 miles of streams under regulation overseen by the state Department of Environmental Conservation.

According to Cuomo, that was precisely the problem.

“While well-intentioned, this bill would have a tremendous fiscal impact on state and local government. It would more than double DEC’s existing planning and oversight role, adding approximately 40,000 miles of Class C streams over and above the 36,600 miles of streams class A & B subject to DEC permitting authority currently,” he wrote in his veto message.

“The workload on DEC alone, associated with reviewing, issuing and enforcing permits associated with disturbance of these resources, cannot be accomplished without adding significant numbers of full-time staff. Moving forward with such a significant expansion of the DEC’s water program without addressing the funding needs would lead to lengthy permitting delays, and jeopardizing the thorough and necessary review of all projects,” the governor continued. He argued that even streams that fall outside the Protection of Waters program are subject to meaningful oversight.

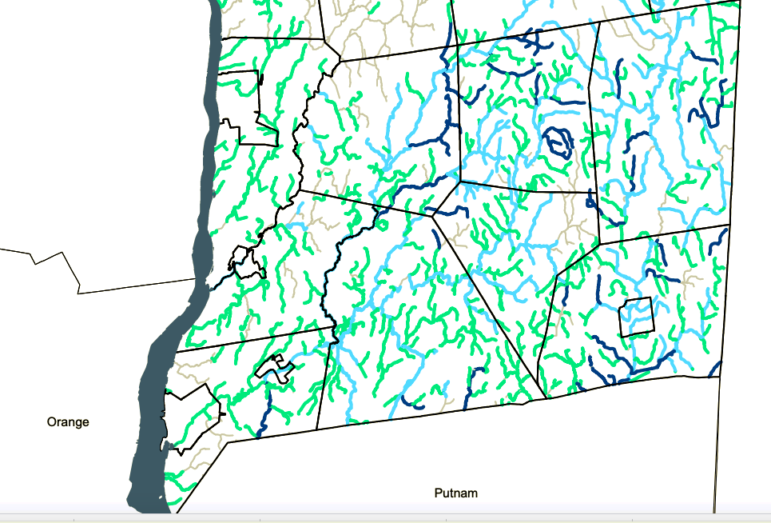

Dutchess County/Riverkeeper

Class C Streams in Dutchess County. The light and dark blue streams are designated as trout habitats or spawning grounds and so fall under the state’s Protection of Waters regulations. The green ones do not.Advocates argued the decision was penny wise and pound foolish.

“Governor Cuomo passed up a real opportunity to safeguard tens of thousands of miles of headwater streams and creeks in New York,” Riverkeeper’s legislative advocacy manager, Jeremy Cherson, said in a statement. “Half of New York’s streams are vulnerable to degradation and are not protected by DEC’s Protection of Waters Program, leaving them vulnerable to disturbance and destruction. This veto was a mistake, since it is cheaper to protect streams proactively than spend far more later to restore them once the damage is done. We urge the governor to work with the legislature to protect our drinking water and fish habitat by strengthening the Protection of Waters Program.”

The $3 billion Mother Nature Bond Act might have provided a funding source for stream protection projects, advocates note. Cuomo pulled that measure from the ballot during the summer, citing fiscal prudence.

Opponents of the bill cited more than fiscal concerns. A group of upstate Republican lawmakers wrote to the governor last week claiming the law would create a “more time-consuming, costly, over-regulated, and impractical state-level permitting process for stream-related projects involving flood repair and mitigation, bridge and culvert maintenance, farmland protection, and other public works priorities.” The New York Farm Bureau opposed the bill, saying it “would hinder farmers’ ability to quickly clear water ways, waiting to obtain a permit could be time consuming and farmers do not have extra time when protecting their crops from nature’s elements.”

But advocates for the additional protections said they were especially important given the Trump administration’s moves to roll back water protections—which the Biden administration will face hurdles dismantling.

One thought on “Cuomo Kills Bill to Protect Streams, Citing Fiscal Woes”

Cuomo is a hypocrite, he says he’s a “green” governor, then he vetoes green legislation!