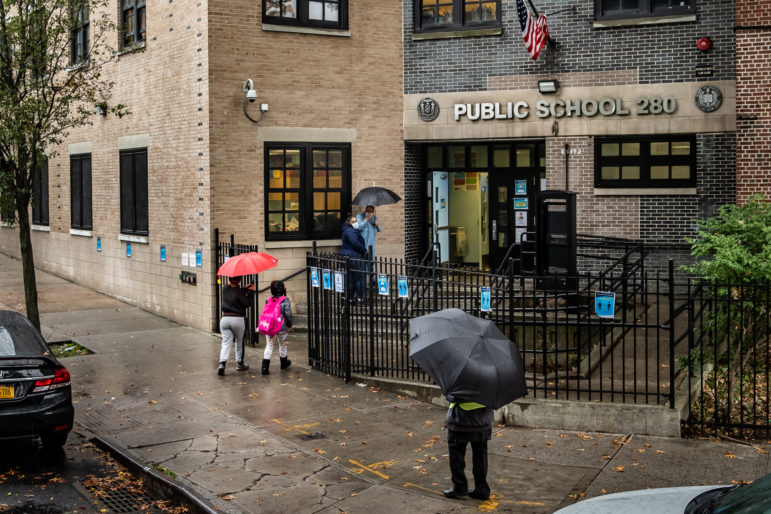

Coronavirus infection rates have remained low in the school system even as cases across the city rise, prompting officials to take a new reopening approach this month. But questions and uncertainty remain.

Adi Talwar

A late October Monday Morning in front of Public School 280 in the Bronx.At a press conference Sunday, Mayor Bill de Blasio announced a new phased re-opening plan for the city’s schools, following a systemwide closure on Nov. 19 after the city’s COVID-19 positivity rate surpassed 3 percent, the threshold set earlier this fall.

Unlike the approach taken at the start of this school year, the new plan does not include a threshold at which schools close system-wide. With increased testing, required consent forms from parents for testing, and having had the experience of monitoring cases among students and staff this fall, the mayor says, “The previous approach doesn’t apply anymore.”

The NYC Department of Education reports that from Sept. 14 to Nov. 30, a total of 1,420 students and 1,891 staff members tested positive for the coronavirus, leading to 1,929 classroom closures since the start of the school year. Given that there are approximately 1 million students in the city’s school system and roughly half chose blended learning, the positivity rate in schools is still quite low: 0.28 percent as of Sunday, officials said. However, when there are positive cases, families who opted for in-person learning often find out about the temporary closures abruptly, which can make it even more stressful and difficult for both parents and kids to adjust — all during a time that’s already stressful and difficult for families, and requires a whole lot of adjusting.

In-person learning is crucial for connecting students to their peers, resources, and academic and emotional support. Yet the city’s decision to provide a part-remote, part-in-person option for students at the start of the year has also contributed to the uncertainty families have faced, as classrooms or even whole school buildings can be forced to close with little notice due if COVID-19 cases are detected. In addition to the temporary closures for specific schools and classrooms, the system-wide closure last month threw another wrench into helping families feel greater stability in what’s been a chaotic time.

“Routines are really important for children and families,” says Emily Goldmann, a professor at the NYU School of Global Public Health with a background in psychiatric and social epidemiology. “That all gets thrown away.”

The mayor’s new plan prioritizes in-person instruction for elementary and pre-K students, along with District 75 programs, which serve students with autism, significant cognitive delays, and multiple disabilities — a phased-in approach that some leaders and advocates called for months ago. In his comments on Sunday, de Blasio said that elementary and pre-K schools will be the first to open, beginning the week of Dec. 7. District 75 schools will reopen starting on Dec. 10. For schools that have enough space, students will have in-person learning available five days a week.

Middle and high school students will remain in remote-only learning for the time being, according to the mayor.

“We’re not ready for those yet,” he said. “That’s just the plain truth. We will work to get to that day, but we’re not there yet.”

The mayor explained why the city decided to prioritize lower grades, citing the greater educational and social needs younger children have, greater demands on working parents to allow younger kids to participate in remote learning, and the fact that there’s less concern about younger children spreading the virus.

Sudden shifts and uncertainty make a hard time harder

Goldmann notes that in-person instruction plays an important role in children’s learning, socialization, and mental health. And even pre-COVID, access to childcare was a major challenge for working parents, making schools key to their ability to work and make enough income to support their families.

Research has shown that the mental health impact of the pandemic has perhaps been most stark among young people, causing potentially greater lifestyle changes for adolescents and young adults, who are used to spending more time with their peers compared to older people. Goldmann points to a recent study conducted by America’s Promise Alliance of 3,300 high school students nationwide, which found more than 25 percent of respondents reported losing sleep “because of worry, feeling unhappy or depressed, feeling constantly under strain, or experiencing a loss of confidence in themselves.”

“These findings suggest that students are experiencing a collective trauma, and that they and their families would benefit from immediate and ongoing support for basic needs, physical and mental health, and learning opportunities,” the report concludes. “Without that support, this moment in time is likely to have lasting negative effects for this cohort of high school students.”

Keeping a schedule and following a routine as much as possible is really important for helping families feel greater stability during times of crisis, Goldmann says, and schools can help offer that, increasing a sense of community and reminding students that they are cared about.

“The ideal scenario is for children to remain in school,” she says.

But the realities and protracted nature of the pandemic means the consistency of children attending classes in school buildings will be up in the air, back and forth, until COVID-19 is no longer a major threat.

“The approach, [that] the disaster is over and let’s pick up the pieces, is not possible here. The pandemic may have permanent impacts on life. There are a lot of things that may change,” Goldmann says. “I don’t think there is an ideal solution.”

Calls for better remote learning

Some parents, however, feel the city’s efforts since September to offer both hybrid and remote learning has ended up weakening the quality of both.

“The abrupt decision-making by policymakers is simply unconscionable,” Alan Aja, a parent member on the Community Education Council for district 20, told City Limits in an email. District 20 includes schools in neighborhoods such as Bay Ridge, Dyker Heights, Bath Beach, and Bensonhurst, along with the Fort Hamilton Army Base. “We should have protected the health and safety of school staff and learning communities all along by going full on remote the entire year, and providing families the structural support they need to get through the pandemic, given we knew this was inevitable.”

Aja feels the city should have instead focused from the start on addressing the hurdles to making remote learning work better for families, like those who still need WiFi or devices or who speak a language other than English at home. The struggle to keep schools open for any family who chose blended learning has been directing resources and effort away from making remote learning work, he argues, and from ensuring kids with special needs get the consistency they need from in-person classes. He would have liked to see children “be supported at home for those who are able with exceptions for the most vulnerable including children who need in-person specialized support.”

At the start of November, more than half of city families had opted for all-remote learning, and even students who attended school in person had online components to their classes.

“All students are partially remote and most are largely remote,” says Daryl Hornick-Becker, Citizens’ Committee for Children of New York (CCC)’s policy and advocacy associate.

“We agree with those who are perplexed about the desire to keep school closed while other things are open,” he says. But CCC has really been focused on demanding improvements to remote learning, which is affecting everyone, and will continue to as long as COVID-19 sticks around.

“The long-term uncertainty underscores even more the need to get remote learning right,” he says.

In a statement to City Limits, the DOE acknowledged the difficulties of the school year.

“We know this isn’t easy, and thanks to New York City’s incredible teachers, staff and families, our kids are receiving the high-quality instruction they deserve,” the statement reads. “Our system was specifically set up for the seamless transition between in-person and remote learning, and our students will remain engaged with rigorous content aligned to grade-level standards, whether they are in school buildings or at home.”

But some question whether the city’s new approach to school closures will address the issues and inequities that many have been raising for months.

“There are questions that still need to be answered,” City Councilman Mark Treyger, who heads the council’s education committee, said on Twitter Sunday. “How will the DOE provide more support for teachers to improve remote learning delivery? What is the plan to address growing class size concerns in remote classes? What is the plan for students with IEPs that do not attend D75 schools?”

Adi Talwar

John Wayne Elementary School (P.S. 380) located at 370 Marcy Ave.“Two separate schools systems”

On Nov. 19, parents and students gathered at City Hall to rally against the mayor’s decision to put a halt to in-person learning. The rally received widespread news coverage, expressing a mostly consistent narrative: that parents want schools to stay open, especially because the most vulnerable students need in-person instruction. While many parents did oppose de Blasio’s decision to close schools system-wide, others are frustrated with a lack of nuance in conversations about remote versus in-person learning.

Tajh Sutton is involved with a whole host of civic groups in addition to being a parent herself: She’s the Community Education Council president for District 14, which includes schools in Williamsburg and Greenpoint, Brooklyn. Sutton’s also the program manager for Teens Take Charge and serves on the steering committees for Parents for Responsive Equitable Safe Schools Steering Committee and Black Lives Matter At School. “As parent leaders, that adds an additional layer,” she says, “because you’re worried about your family and you have to advocate.”

Sutton says that protesters at the rally to keep schools open tended to use language such as “our most vulnerable students” to justify their demand not to close schools. “So the idea seems to be,” she says, “that we know low-income students and students of color have been disproportionately impacted by the pandemic and so on. The language being used suggests that the schools need to stay open for those kids.”

But data shows that many students of color are among the more than 503,000 students who’ve opted for full-time remote learning: the DOE reported on Oct. 13 that 70 percent of Asian students, 50 percent of Black students, 50 percent of Hispanic students and 39 percent of white students chose remote-only classes.

Yuli Hsu is the parent of two elementary school kids in Brooklyn who are both in full-remote learning, and serves as the Community Education Council District 14 vice president as well as a member of the Parents for Responsive Equitable Safe Schools (PRESS NYC) Steering Committee. She says that the opening versus anti-opening debate is a false narrative. “We have always advocated for the safe, prioritized reopening of schools.”

The unpredictability of classrooms and school buildings intermittently reopening and closing has a big effect on full-remote students as well, says Hsu. She says parents on the District 14 CEC board have been asking for weeks and months for a plan if schools close again.

“If all the kids are on remote, how are we going to shuffle schedules and classes so everybody is accommodated?” she asked.

Hsu argues that NYC has essentially had two separate school systems since the start of the school year: a 100 percent remote system and a hybrid system, which are at odds with one another when they should be complementary. After all, when schools do close in-person instruction, blended learning students go fully remote. However, Hsu expressed frustration that there hasn’t been transparency from anyone — the chancellor all the way down to the superintendent and principals — on what that plan or guidelines are for how decisions for in-person learning will affect all-remote learners.

“It’s always kind of like, ‘Well, you know, we have a situation room, we will take care of it, they will tell us what to do.’ But it’s always too little too late,” she says.

This reality has pitted blended and full-remote parents against each other, she says. The logistical challenge of keeping track of COVID-19 cases, closing and reopening classrooms and school buildings, has been a huge focus for the DOE and occupied resources that could have benefited remote learners. Teaching students remotely comes with its own logistical challenges, like making sure students have access to WiFi and devices as well as being able to communicate with families so they can help children learn at home.

If the city had limited the availability of in-person instruction for a smaller group of students, for example students with IEP accommodations or special needs and ESL, they might have been able to limit some of the logistical challenges and conserve time and resources for the many other issues to resolve for educating students during a pandemic, some parents argue.

Kenyatta Reid, also CEC 14 member, has two children in full-remote learning and one toddler at home. One of her kids is having trouble with reading; she wishes she could start getting her child IEP accommodations and knows that in-person instruction would be helpful. Yet, she says, she made the decision to keep both school-aged children home due to the risks of the pandemic, even though it’s been difficult to help one child through academics and care for a toddler at the same time.

“My older son needs me too,” she says. “Even as an overly involved parent, I still feel lost on what the DOE is doing, district and citywide.”

Nicole Javorsky is a Report for America corps member.