Local legislators are trying to find options to prevent 3.1 million immigrant people from continuing to bear the heaviest brunt of the crisis.

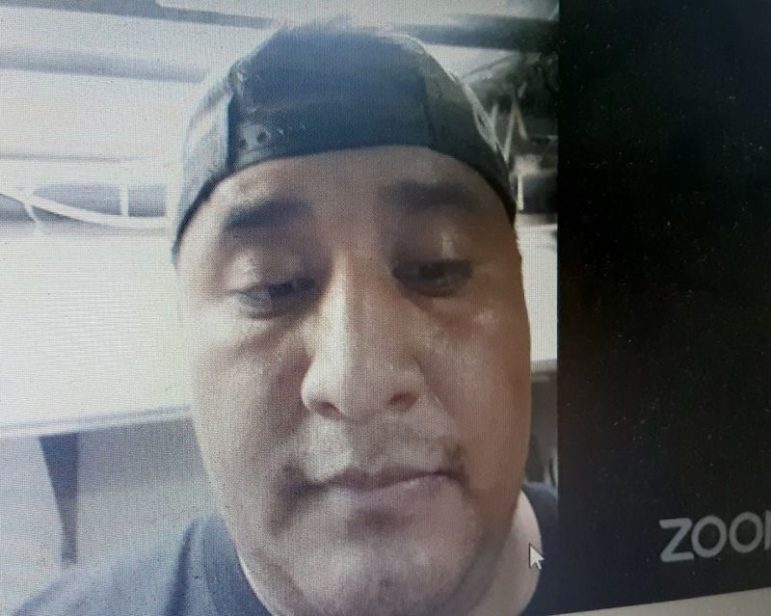

Fernando Martínez

Guatemalan delivery man William Asian described instances of abuse at work.This story was published in El Diario.

Translated by Carlos Rodriguez from Spanish.

William Asian, a Guatemalan delivery man, is only one of hundreds of New Yorkers for whom COVID-19 continues to have a devastating effect. On Wednesday, his voice was heard loudly at a virtual hearing held by the Committee on Immigration of the New York City Council, which is evaluating ways to bring relief to those who were excluded from all pandemic-related aid.

“I came to the Big Apple in 2011 to find a better future. I was one of the thousands of essential workers who kept delivering food despite the risk. I did not have the choice to lock down, especially after losing my job at the restaurant where I worked,” Asian explained.

In deep financial straits and as a way to survive, Asian turned to working for online delivery apps – which have become very popular during the pandemic. Doing this forced him to deal with another bitter daily reality endured by the working class: worker exploitation.

“With these apps, you have to work up to 50 hours in order to make $400. They steal our tips, and we cannot file a claim. They block you every time a customer writes a bad review. We have to pay for our own bike and protective gear,” said Asian, who is now an activist for the Worker’s Justice Project. He is asking for some kind of “breathing room” for the workers he represents.

Asian’s testimony illustrated an experience that has multiplied exponentially on every corner of New York City’s five boroughs six months into the pandemic. The situation has led local legislators to try to find options to prevent 3.1 million immigrant people from continuing to bear the heaviest brunt of this crisis.

To this end, Brooklyn Councilman Carlos Menchaca, chair of the City Council’s Committee on Immigration, announced the passage of six resolutions, one of which encourages the state Assembly and Senate to allow state and municipal agencies to expand certain public benefits to people regardless of their immigration status.

These petitions, also sponsored by Councilman Francisco Moya, include requesting the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) to halt deportation plans. Another one asks Congress to approve a law allowing people with work permits whose jobs are related to the pandemic to keep their legal status even after being laid off.

“We have listened to the words of these immigrant workers very attentively,” said Menchaca. “This is a moment when a quick and fair response is needed for those who have disproportionately suffered the effects of this crisis, to whom no relief has been made available.”

Mexican immigrant Inok Evangelista also spoke during the online hearing, during which he described a persistent pattern of discrimination and worker abuse, which according to some organizations has only worsen since the pandemic began.

“The only pay I have received since the pandemic started is my last week at the restaurant where I used to work. I have had to turn to assistance centers in order to survive. I work as a delivery man from dawn to dusk just to be able to eat. I have been discriminated against for being Mexican. I hope that my words help make progress towards some type of benefit,” said Evangelista.

Day laborer Jesús Benavides said that most of his fellow workers “never stopped battling against the crisis,” but also that there is a history of abuse regarding worker payments.

“We risked our lives, we lost many of our fellow workers to the virus, and there was no aid of any kind,” said Benavides.

Commissioner of the Mayor’s Office on Immigrant Affairs (MOIA) Bitta Mostofi, who also attended the hearing, said that during the months of “tragedy” that immigrant workers have had to endure, her agency kept in constant contact with community-based organizations in order to contribute to the wellbeing of immigrants within the City’s possibilities and regardless of anyone’s immigration status.

“We guaranteed free medical services, nutritional assistance and prevention policies in 25 languages. Within our range of action, we supported these families, who are part of New York’s riches. Meanwhile, the federal government turns their back on them,” she said.

One thought on “City Council Hears From Immigrants Excluded From COVID Relief”

Hola a todas y todos, mi nombre es Federico de República Dominicana, soy inmigrante, trabajo en el área de la construcción, cuando comenzó la situación del Covid, dure 4 meses sin trabajar, me exigían el pago de la habitación, caí en depresión, a esto se le suma la necesidades básicas y sin oportunidades para paliar resolver, veía a casi tod@s recibir asistencia del estado, mientras yo solo sufría el estrago de la miseria en la nación más rica del planeta, sentí que era injusto que por un estatus migratorio tuviese que vivir casi desahuciado a pesar de tener las ganas de aportar, de trabajar, de ser parte de la solución, la exclusión es algo inapropiado, ojalá que los tomadores de decisiones de esta maravillosa nación puedan hacer algo por corregir esta inhumana práctica de olvidarse de que solo nos diferencia un estatus, pero después tenemos las mismas necesidades, deseos, sentimientos y necesidades