Mayor de Blasio’s initiative to build or preserve 300,000 units of affordable housing seems to be on track. But is it on target?

Adi Talwar

Critics of the mayor’s plan say that rezonings should have targeted some whiter, more affluent neighborhoods with the capacity for more density, like Oakland Gardens.The COVID-19 pandemic has killed more than 20,000 New Yorkers, plunged the city into an economic crisis and left Bill de Blasio’s image in tatters. When he leaves office in a little more than 15 months, de Blasio will likely be one of the least admired mayors in the city’s history, the stain of 2020 blotting out universal pre-K, the ending of stop-and-frisk and other accomplishments.

The mayor’s physical legacy, however, will be harder to erase. Despite practical obstacles created by the pandemic and a budget shift because of the fiscal crisis, the administration expects to hit the goals de Blasio originally set back in 2015, and to be on pace for the more ambitious targets he adopted in 2017.

It’s unclear, however, what impact those efforts have really had on affordability in the city—and whether there is any way for the de Blasio team to change their approach and make a deeper difference in the time it has left.

Numerical successes

On a sunny, May day in 2014 in Brooklyn, de Blasio first introduced an ambitious affordable housing plan aimed at creating or preserving 200,000 housing units across the five boroughs over a 10-year period. In 2017, the city administration upped the goal to 300,000 housing units: 120,000 new units and 180,000 preserved units by the year 2026—well past de Blasio’s second mayoral term. The total cost of the housing plan is projected to be $82.6 billion, funded by a combination of city money, state and federal support, and private investment.

It was one of the most aggressive housing plans in the country. Housing advocates say the de Blasio administration kept laser focus on producing the goal of generating a large number of housing units. And it was successful in hitting those targets.

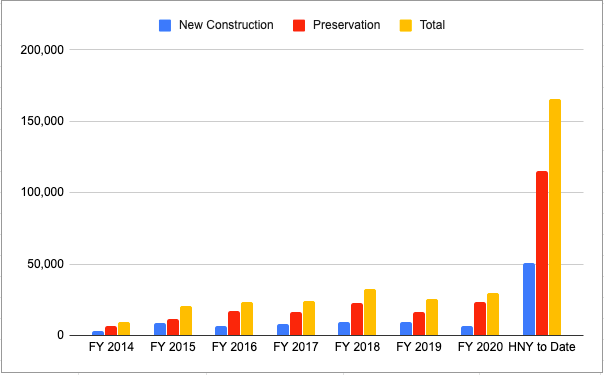

As of June 30th, there are a total of 165,690 affordable housing units completed so far: 50,656 (31 percent) are newly constructed and 114,934 (69 percent) have been preserved, according to the city’s Housing Preservation Development (HPD). The housing unit number has increased with every fiscal year and an HPD spokesperson said the city expects to meet the housing plan’s first goal of 200,000 housing units by its deadline in 2022 after the end of de Blasio’s mayoral term.*

The 165,000 number is significant: That was the goal set in the city’s previous plan, which Mayor Bloomberg unveiled at the beginning of the second of his three terms.

The de Blasio administration “put out a goal and it held itself accountable for that goal and then accomplished it. It hit the 200,000 unit mark [and] they did an update that was maybe a little ambitious, especially since now there’s the financial downturn,” says Moses Gates, the Regional Plan Association’s vice president for housing and neighborhood planning. “But not only was the 200,000 unit target accomplished, the nuances of that were better than the Bloomberg nuances. It was more deeply affordable units.”

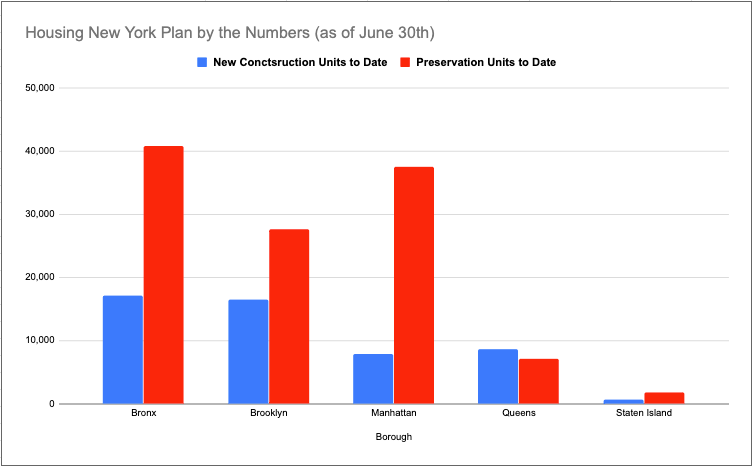

The de Blasio plan, known as Housing New York, has left the largest footprint in the Bronx, where there have been a total of 57,980 affordable housing units—17,143 are newly constructed and 40,837 are preserved. Manhattan and Brooklyn saw the bulk to rest of the units.

“The biggest success is just the overall scope of it. I think it’s important not to lose sight of how ambitious the mayor’s housing plan was when he came into office, certainly from a production standpoint. That’s really, really major. I think his willingness to put it front and center was important,” says Patrick Boyle, director of policy at the New York State Association For Affordable Housing (NYSAFAH). “It means that there’s lots of affordable housing units being created, which is, really life altering for those people that are able to have access to those units.”

De Blasio benefited from deep experience within HPD, which had dealt with Bloomberg’s plan and, before it, Mayor Koch’s 1986 “Ten-Year Plan” for 250,000 units of affordable housing. While Koch’s plan might not have actually created a quarter of a million units, it did set in motion construction and preservation efforts that continued into the Dinkins and Giuliani administrations.

“I think what the last several administrations has done is to create an engine that develops affordable housing at the municipal government level that doesn’t exist anywhere else. It’s a remarkable government structure that creates more affordable housing units than anywhere,” says Jessica Katz, executive director at Citizens Housing & Planning Council.

Other things, the de Blasio team did less well, like developing. the communication strategy for the public. A message about “why the housing plan was important and its successes” was not effectively conveyed, Katz says.

Rezoning battles: One remains

De Blasio’s plan included the rezoning of 15 city neighborhoods to create more density for both market-rate and affordable housing. So far the city administration has successfully approved six rezonings: East New York, Downtown Far Rockaway, East Harlem, Jerome Avenue and Inwood.

At least three of the rezonings—in East Harlem, Inwood and Jerome Avenue—prompted bruising battles involving City Hall, local pols and neighborhood groups. The mayor’s tendency to target low-income communities of color for rezoning, rather than asking wealthier areas to absorb new housing, led to increasing resistance. Efforts to rezone parts of Southern Boulevard in the Bronx and Bushwick in Brooklyn fell apart over the past year. With less than 16 months left in the mayor’s second and final term, the last remaining rezoning will likely be Gowanus in Brooklyn.

The rezonings included the mandatory inclusionary housing (MIH) rule approved by City Council in 2016. Today every neighborhood upzoning requires developers building in the rezoned area to provide a percentage of the new housing units at “affordable” rents, with rent levels defined by the city. Under MIH, the city has created 2,247 housing units in total since the MIH was enacted in 2016.

There remains intense debate over whether the rezonings will create truly affordable units or instead drive speculation and gentrification. As was the case with Bloomberg’s affordable housing, rents on many of de Blasio’s “affordable” units are out of step with resident incomes in the area targeted for rezonings, although he did shift his plan to target lower-rent units in 2017.

Advocates across the board said the city should have focused some of the rezonings in less diverse areas such as the West side of Manhattan, North Brooklyn or Long Island City where there has been a concentration of high end construction. Boyle says neighborhoods such as Oakland Gardens or Bayside in Queens or Coney Island in Brooklyn, where affordable housing is rare if nonexistent, are ideal for MIH housing to exist because those neighborhoods fall under the middle to higher income ranges and foster living-wage job opportunities for those who may be come from lower income households.

Getting pushed, making progress

Emily Goldstein, director of organizing and advocacy at the Association of Neighborhood and Housing Development (ANHD), says the de Blasio housing plan brought advocacy groups together to push for tenant and housing reforms through state and city legislature.

“We’ve made huge strides and really have shifted the parameters of anti-displacement and anti-eviction policy in the city. A lot of that came from enormous amounts of organizing and advocacy from tenants and affordable housing providers and the movement of people in New York who care about affordable housing,” says Goldstein.

Landmark victories include the Right to Counsel law, also known as Universal Access to Counsel, which gives low-income tenants facing evictions free legal support in housing court, and the Certificate of No Harassment law, which requires property owners of certain buildings to show a slate clean of tenant harassment complaints before acquiring permits from city’s Department of Buildings for any construction work which would require demolition or changes in use or occupancy.

The City Council also passed the Tenant Protection Plan (TTP) in 2018 which aims to ensure the safety and quality of life for occupants during construction work.

While de Blasio did not propose those moves, and in some cases resisted them, Goldstein said his housing plan triggered an opportunity for advocates to push the city to go a few steps further to protect vulnerable residents in low-income and minority neighborhoods from facing displacement, evictions, bad-acting landlords and aggressive speculative investors.

After a push from housing and tenant advocacy groups, the revamped housing plan in 2017 included anti-displacement strategies. One was the Neighborhood Pillars program which partners with nonprofits to purchase and renovate rent-regulated units in buildings in speculative markets. Another was Partners in Preservation, where HPD works with community-based organizations to develop comprehensive anti-displacement plans.

Advocates also pushed for affordable housing income levels to go deeper for those extremely low-income households and for the city to create more permanent housing. The de Blasio administration in 2017 increased the number of housing units for households making below 50 percent Area Median Income (AMI) from 20 percent to 25 percent of the housing plan.

What the housing plan overlooked

Advocates say the focus on numerical production allowed for other opportunities—community land trusts, homeownership and mitigating adverse impacts of rezoning in low-income minority neighborhoods—to be overlooked by the city administration.

“There were a lot of lost opportunities to try to really change the provision of how affordable housing works,” Gates says. “The de Blasio housing plan was not any kind of paradigm shift over the way business is done in New York from Bloomberg. So while the housing plan was ramped up, and it was, I would say it didn’t really challenge any underlying systemic issues of affordable housing in New York.”

Two other flaws of the de Blasio housing plan were leaving out NYCHA and its treatment of homelessness.

Katz said the housing plan did not include NYCHA because it was already considered affordable housing and it was decided early on that it could not count, which left NYCHA residents with no help and in disrepair. While de Blasio did issue a series of strategies to save NYCHA, and inject huge amounts of money, some thought it odd that the city was spending billions to build new affordable housing while, on NYCHA campuses, its existing supply was crumbling.

On homelessness, City Hall’s power structure made it difficult to harness the housing plan to the best of its ability to help more homeless families in New York City, “The HPD commissioner and the DHS commissioner report to different deputy mayors. The two are just running on parallel track,” Katz says. “So I think the chain of command in City Hall made it harder for those goals to work towards each other.”

The de Blasio administration did move large numbers of homeless families to permanent housing, but resisted efforts to give homeless households a sizable chunk of the new units created in every affordable development. Under the plan, an estimated 12,941 housing units serve the homeless population.

Meanwhile, there was little to no cooperation between the state and city governments on supportive housing, which combines social and medical services under one roof.

The mayor’s harsher critics believe, unit-count notwithstanding, that his housing has fallen short of its deeper goal of making it easier for families to live in New York.

“If you look at any of the metrics, if you look at rent burdens, if you look at racial and economic segregation, if you look at how many people are homeless, everything has gotten worse,” says Goldtstein. “I think for a mayor that came in talking about the tale of two cities and talking about equity and addressing the needs of the vast majority of New Yorkers who are dealing in one way or another with an affordability crisis—in total that affordability crisis has only gotten worse.”

The road ahead

Today, the city is looking at a $9 billion dollar budget gap with no help in sight from the federal government or Albany in the near future. The de Blasio administration tapped into $4 billion of the city’s reserve to make the current budget’s numbers work, according to the City Council.

In July, the city’s housing agency, the Department of Housing Preservation and Development, saw its capital budget decreased from $1.48 billion to $902 million in fiscal 2020 and from $1.19 billion to $741 million in fiscal 2021, pushing more than 40 percent of the capital program for affordable housing into later fiscal years.

The question is what impact those shifts will have on the administration’s ability to build out the plan at pace. In August, the city announced it had financed 30,023 affordable homes in fiscal year 2020. But there was a huge drop in new construction housing units from 9,141 units in 2019 to 6,504 units in 2020.

“This administration has already financed a record number of affordable homes and will continue to push forward the city’s ambitious housing plan. HPD’s work has provided an essential safety net in past downturns, and we’re more committed to our mission than ever. The need for affordable housing has never been greater – that’s why the city needs state and federal resources to see the city through this crisis,” said the HPD spokesperson in an email statement to City Limits.

There have been suggestions for how de Blasio might use what is left of his term to impact affordability. Restoring the basement apartment pilot, which aimed to legalize a part of the city’s affordable-housing stock that could also help moderate-income homeowners, is one idea. Although controversial, some have pushed for the completion of a SoHo-NoHo rezoning, or the beginning of an effort to rezone and increase affordability in Sunset Park. Others believe now is the time to invest heavily in community land trusts.

Almost everyone, however, has an eye on the 2021 mayoral election and the next administration—and the chance not to fix the de Blasio housing initiative, but launch a new one.

“I can’t predict the future, but I do think there’s a huge opportunity, frankly, less in shifting the existing plan than in making a break with the current paradigm and starting with a fresh perspective,” says Goldstein. “So I think my hope is that we’re going to see goals that are really about meeting New Yorkers housing needs, and that are explicitly about racial and economic justice and about reckoning with, and reducing the disparities that are currently present in our city, by race, by income, by geography, all of which overlay very clearly.”

*Clarification: the de Blasio housing plan deadline for 200,000 housing units is for 2022 and the housing plan deadline for an additional 100,000 housing units is slated for 2026. An earlier post said HPD expected to meet its goal by the end of mayoral term.

*In an editing error, the Bay Street rezoning in Staten Island was left out.

One thought on “Amid COVID and Fiscal Woes, Mayor’s Housing Plan Enters Stretch Run”

The best thing NYC can do is to just leave it’s middle-class neighborhoods alone. The poor always drag a neighborhood down, lowering the quality of life and bringing crime with them.