Since its founding two years ago, Efforts in Youth Development in Bangladesh (EYDB) has raised approximately $20,000 to fight poverty and child labor.

Adi Talwar

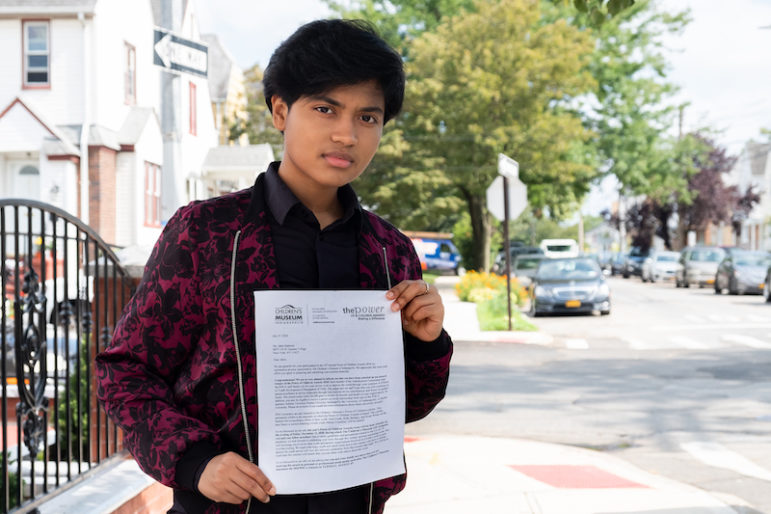

Rising high school senior Jahin Rahman near her home in Queens Village. Rahman holding a letter from The Children’s Museum of Indianapolis informing her of her selection as a Power of Children 2020 awardee. Efforts in Youth Development of Bangladesh a non-profit founded by Rahman provides educational support to poor children in Bangladesh.At the age of eight, Jahin Rahman left her multigenerational household in Bangladesh to pursue more opportunities in America. Now, at 16, she’s a senior at Academy of American Studies in Long Island City and the award-winning founder of Efforts in Youth Development in Bangladesh (EYDB), a New York City student-led organization that seeks to alleviate child poverty by providing quality educational opportunities and resources for at-risk Bangladeshi youth.

The group has raised approximately $20,000* since its founding two years ago, from awards and through grassroots fundraising, which included canvassing on the subway after school for donations—equipped with posters, signs, and a donation cup. With that money, they’ve built a library with over 250 books, opened a computer lab, and plan to partner with a garment factory to help build a child-care facility and establish a literacy program.

Since the start of the pandemic, EYDB has pivoted to provide relief for families in Bangladesh, where the economy has been greatly impacted by COVID-19, including a decline in both exports out of the country and in remittances being sent back home from Bangladeshis living abroad, according to the International Monetary Fund. Rahman and her volunteers, many of them fellow city high-school students, have provided funding to cover the costs of month-long supplies and rations for more than 20 families.

“When I was first starting out, I was just a high-school student looking to start a club,” says Rahman. “Then, I got in contact with the Department of Education’s Student Voice Manager, Amallia Orman, who got us connected with many other schools.” Orman, who was hired as part of DOE Chancellor Richard Carranza’s initiative to involve youth in policy making decisions, helped facilitate outreach with EYDB, amassing around 300 youth volunteers from schools across the U.S. and eventually eight other countries.

Rahman says she was always aware of her privilege back in Bangladesh because she grew up in a large household where income wasn’t an issue. As soon as she stepped outside of her house, however, she’d see many malnourished children living in slums nearby, without shelter.

“But I kind of got used to it because I was seeing it all the time and that was really sad,” she says.

Though the poverty rate in Bangladesh has declined in recent years, the share of the population living on less than the equivalent of $1.90 a day—the World Bank’s poverty threshold—stands at 14.8 percent. The U.S. rate, for comparison, is 1.2 percent.

To address these statistics, Rahman started EYDB with the help of her high-school friends and teachers from the Academy of American Studies, brainstorming ways to raise money for anti-poverty initiatives in Bangladesh. They drew inspiration from Mohammad Yunis, a 2006 Nobel Peace Prize winner and founder of the microcredit concept. Built on the principle that credit should be a human right, Yunis gave out numerous micro-loans with affordable interest rates, transforming the lives of many poor Bangladeshi people, especially women.

“I found it so fascinating that the concept of microfinance has gotten so many people out of poverty,” Rahman says. “It made me realize that I want to do something like that one day.”

During the first year of EYDB’s launch in 2018, Rahman and her fellow members would spend their afternoons after school fundraising at subway stations: Armed with posters and a donation cup, they’d take the F, E or 7 train, choose a location, and start canvassing. Sometimes, train-goers would hear their conversations and would donate money on the spot.

“When EYDB began it was just me and my close friends and it was at first difficult to fundraise in public,” says Kuenley Dorji, 16, a senior at Academy of American Studies in Long Island City and fellow members of the group. “However, over time I learned how to adjust and became confident enough to reach out to strangers who were willing to listen to our cause.”

Using Rahman’s family connections, EYDB started organizing in Dhaka, Bangladesh by partnering up with a local non-profit there called Beacon Point, a group that focuses on mental health outreach. In the past two years, EDYB has opened up a computer lab, established a literacy program and built a small library by filling an empty Beacon Point room with over 250 books for children.

They also recently partnered with BRAC, an international anti-poverty organization, to fundraise for the creation of daycare facilities in factories around Dhaka, where women laborers are in desperate need of childcare during long work hours. According to UN Women, female domestic workers and their families are bearing the brunt of the pandemic in Bangladesh: The country tried to curb the spread through strict lockdown measures, leaving many domestic workers without income since they cannot perform house chores in other people’s homes. EYDB quickly adapted to those new realities by reallocating funds to immediately send assistance to over 20 Bangladeshi families impacted by the pandemic.

The group has ambitious plans for other future projects. They hope to expand Beacon Point’s existing adult drug-rehabilitation center to provide mental-health and addiction counseling services to troubled youth who are also coping with drug addiction, establish a hygiene and sanitation program for female students in rural schools throughout Bangladesh, and in 2021, they want to create a boat museum in the Brahmaputra shore to feature art made by local Bangladeshi children.

One of their biggest priorities is to tackle child labor. The U.S. Department of Labor’s most recent 2018 study states that Bangladeshi youths aged 5 to 14 are involved in some of the worst forms of forced child labor in the world, and the government there often does not have the enforcement capacity to deal with the growing child-labor force. Moreover, there aren’t enough laws in place to protect children working in the unregulated informal sector, where child laborers are paid in untaxed cash.

The Bangladesh National Child Labour Survey indicates that approximately 4.7 million children from ages 5 to 14 work, and about 2.6 million children in that age group do not get the opportunity to attend school, since they start working at a young age to survive. The survey estimates that about 1.3 million girls in this age group work full-time.

“If you tell families, ‘Please send your daughters to school,’ that may be a great initiative. But the reason why they sent their daughters to work is because they need the money,” says Rahman.

One of EYDB’s current efforts is to address those educational disparities in Bangladesh by fundraising to cover the costs of schooling for young girls, providing them with an educational stipend will allow them to go to school, avoid hazardous work conditions and support their families. This initiative, called EMERGE, won the Citi Foundation Gender Equality Challenge in the 2019 Network for Teaching Entrepreneurship (NFTE) World Series of Innovation, a contest that provides cash prizes to youth entrepreneurs with ideas for solving global problems.

“We are going to provide a $20-a-month [stipend] per family, which converts to about 1,700 Takas,” the currency used in Bangladesh, Rahman explains. “$20 may not seem like a lot, but many of these child laborers only make $12 a month on average.”

While COVID-19 has halted in-person fundraising for EYDB, it certainly has not stopped Rahman and her classmates from finding innovative ways to continue working to meet their goals virtually. This past summer, EYDB partnered up with other organizations like Interns 4 Good, a virtual platform that connects high school students to non-profits for volunteer and professional development opportunities. During the first few months of the pandemic, over 102 volunteers trained virtually with Rahman on Zoom, sometimes taking place late at night to accommodate volunteers from other time zones.

The volunteers created packets that include educational materials with lessons on math, Bengali and art for children from kindergarten to eighth grade. Rahman plans to use Beacon Point and BRAC’s networks and resources to put together a local team to distribute these materials to 4,000 street children in Bangladesh starting this fall.“I believe that EYDB is a step closer to ending poverty in Bangladesh,” says 14-year-old Fahmin Rahman, who attends the Gateway to Health Sciences Secondary School* and serves as the group’s secretary. “It makes me feel inspired to do something, though small but meaningful, for my nation and for its children.”

*The original article was updated to correct the amount of money raised and the name of the school Fahim Rahman attends.