Share This Article

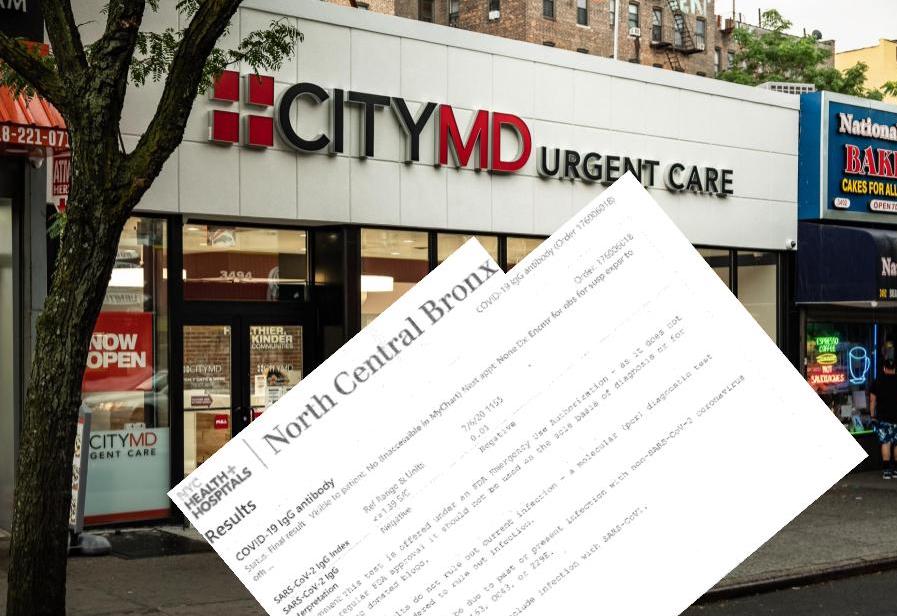

Adi Talwar/J. Murphy

COVID-19 antibody testing is available at 22 Health + Hospitals affiliated locations as well as a number of private sites, including City MD locations.Numerous scientific terms have been introduced into everyday conversation over the past several months, due to the enormous impact COVID-19 has had on daily life.

“We’re asking people to have a crash course in epidemiology, virology, immunology, genetics. We are throwing around these very scientific terms that people have never heard of,” says Danielle Ompad, an epidemiologist at NYU School of Global Public Health. “People are confused because it’s complicated stuff. It’s not part of the general knowledge.”

The term “antibodies” is one example of a scientific term that’s now crucial for understanding the antibody tests available to the public, which is a different test than the COVID-19 diagnostic test.

With the diagnostic test, healthcare providers may use a nasal swab, oral swab, or saliva sample to test for an active infection. When someone tests positive on the diagnostic test, their doctor will tell them to quarantine and stay away from others, assess symptoms, monitor the patient for symptoms and figure out the best way to treat them.

Unlike the diagnostic test, the COVID-19 antibody test is a blood test to find antibodies, which are proteins that the body produces in response to an antigen. In this case, the antigen is COVID-19.

New York State conducted a survey of antibody testing across the state and the results announced on May 2 showed 12.3 percent of antibody tests for 15,000 people throughout the state were positive. Of those tested for COVID-19 antibodies in the state’s antibody testing study in New York City specifically, 19.9 percent tested positive.

What does a positive antibody test result mean?

One of the major open questions surrounding COVID-19 is if people who contract the virus develop immunity and how long immunity could last. Until scientists gain a more precise understanding of immunity to COVID-19, individuals’ antibody test results are not very significant for decisions about one’s personal health. In other words, if someone went to an urgent care to get tested for antibodies and got a positive result, they should behave as if they can get infected again. The scientific research done so far provides no guarantee of immunity to reinfection.

That’s why public health professionals say people who test positive for antibodies should continue preventative behaviors like mask-wearing, hand-washing, and social distancing.

“There’s no guarantee that you’re protected and it’s not just about you,” says Ompad. “It’s about your family and your community and the grocery workers and many others who’ve had to continue working.”

She adds, “We don’t even know if people can get reinfected or not, or if people can have their infection reactivated.”

The new coronavirus that emerged in Wuhan, China during December 2019 is part of a large family of coronaviruses that are known to cause illness, World Health Organization notes, ranging from the common cold to more severe diseases such as Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS). For instance, MIT Technology Review notes that each year there tends to be widespread circulation of four coronaviruses (HKU1, 229E, NL63, and OC43). These four coronaviruses cause common colds, posing far less risk to public health than a virus like COVID-19 that can cause more severe symptoms.

Researchers at Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health studied the immune response to these coronaviruses (HKU1, 229E, NL63, and OC43), using data in New York City from fall 2016 to spring 2018. They found people had gotten reinfected with the same coronavirus more than once even within the same year. This research suggests that antibodies for at least some kinds of viruses within the broader family of coronaviruses may not protect against reinfection. Matthew Frieman, who studies coronaviruses at the University of Maryland, told MIT Technology Review, “We really don’t understand whether it is a change in the virus over time or antibodies that don’t protect from infection.” In contrast, people who contract diseases like measles or chickenpox can recover and develop lifelong immunity.

Bruce Y. Lee, a health policy and management expert at CUNY School of Public Health, emphasizes that the case is not closed on what positive antibody tests mean for immunity to COVID-19.

“With antibodies and immunity, it’s complex. The immune system is complex,” he says. “That’s why it’s taking time to figure out. What we are facing right now is a lot of messages on social media and from politicians that try to simplify the issues in the pandemic.”

The results of two studies published last month suggest that people who contracted COVID-19 could become reinfected within just weeks or months if exposed again. And it’ll take additional research before scientists have sufficient evidence to better understand the relationship between antibodies and immunity for COVID-19.

In fact, both the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and WHO make clear that the current science on COVID-19 has not shown whether or not someone who tests positive for antibodies can get infected again. The CDC notes, “Having antibodies to the virus that causes COVID-19 may provide protection from getting infected with the virus again. If it does, we do not know how much protection the antibodies may provide or how long this protection may last.” Similarly, WHO explains on an FAQ page about antibody tests that “there is currently no evidence to determine whether or not people who have recovered from COVID-19 and have antibodies are protected from a second infection.”

“The jury is still out on whether antibodies signal immunity. It’s still an active, changing story,” Lee says.

Differences between antibodies

When a substance (imagine the spike protein for the COVID-19 virus, for example) enters the body, the immune system recognizes it as foreign when the molecules on the surface of the antigen differ from those found in the body. During the immune response, the body produces protective proteins called antibodies, also known as immunoglobulins.

There are five main classes of antibodies, including IgM and IgG. IgM is one of the first antibodies the body produces in response to an antigen. IgG, which is the most common type of antibody found in the blood, tends to be produced later in the immune response. Most COVID-19 antibody tests look for IgG and some also look for IgM.

“Your antibodies are what are called the adaptive immune system. That means your body produces antibodies that are tailored to whatever the infectious disease is,” Ompad explains. “IgM is one of the first antibodies you produce in response to an antigen and it’s very general.”

Ompad uses the metaphor of boxing matches. “If there’s a new competitor, your approach is going to be broad until you figure out your competitor’s weaknesses. That’s IgM because it’s like a general immune response, but it’s not highly targeted.”

Conversely, IgG is “very tailored and more efficient,” she says. “It’s like the fourth round of the boxing [match]. If I know you favor your left side, I’ll do a left hook.”

Good tests and bad

There’s also the possibility of a false positive or false negative result.

Lee cautions that “there’s a variety in performance for antibody tests.” He says, “Don’t do mail-order antibody tests. Don’t do any testing from individuals who contact you. There are a lot of people trying to make a buck. Even if you go to a known facility, ask what test they’re using and look it up on the FDA site.”

The FDA’s website includes all of the serology tests (blood tests) authorized by the government to test for COVID-19 antibodies, noting measures of test performance for accurately detecting antibodies in the blood.

How antibody test results can help the public health response to COVID

Back in the winter, during the early months of community transmission in New York, testing to be diagnosed for an active infection of the new virus was extremely limited. A large number of the New Yorkers who got tested early on had severe cases and were symptomatic. For this reason, a significant percentage of cases, especially during the early months of 2020, were never recorded by the health department.

Nischay Mishra, who is a professor of epidemiology at the Center for Infection and Immunity at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health, says antibody tests can help public health professionals gain a better grasp of how COVID-19 has spread historically. He explains that it’s an “indirect approach” to fill in the gaps in data created by the very limited testing available during the early months of the pandemic.

Lee agrees, “The problem is at the very beginning, testing was very reactive: If someone shows up at the emergency room, for example … A lot of policy and a lot of what we do is affected by how many people have gotten infected and where.”

“Where has the virus been and where is it going? That helps us figure out where to direct healthcare resources, where to focus further testing,” he adds.

Although maps of case counts are ubiquitous, Lee says that “everyone agrees the maps are not accurate. Those are reported cases. Those are undercounts. The question is by how much? And where?”

Widespread antibody testing can help bolster the data public health experts use to make recommendations about how to move forward. Lee emphasizes that testing, which includes diagnostic tests to understand the number of current infections and antibody tests, is crucial for determining public health strategies.

Fighting the spread of COVID-19 without testing, he says, is “analogous to a football game where you don’t know where the opponents are and you can’t see the whole field. How can you effectively come up with a strategy and game plan? And you don’t even know the score.”

In conjunction with the diagnostic tests which identify new COVID-19 infections, antibody testing data can help health officials identify new hotspots early. For example, if a neighborhood has rising cases and low levels of positive antibody tests, that could prompt targeted action to contain spread in the surrounding geographic area and signal the area might need more healthcare resources soon.

Lee says at the moment, there is not enough data in New York City to target policy based on situations unfolding in various spots of the city. However, the virus is still having ranging effects by neighborhood. “We need to have a tailored response to the situation,” he says. “We don’t want to get in this cycle of broad policy and close, broad policy and open.”

So while antibody test results don’t play a significant role in personal health decisions as of yet, the information that widespread antibody testing can provide is crucial to help contain the virus. Plus, Ompad points out that at some point in the future, when antibody test results are useful for one’s personal health, it can be beneficial to have already been tested for antibodies.

“Let’s say in the next month that 20 papers come out that you’re not protected or that you are. At some point, it will have some clinical value,” Ompad says. “Right now, it’s very useful for getting a handle on how many people had [the] disease.”

Tips for patients

She also says antibody tests can reveal that there are many cases where people hadn’t had symptoms, which can help the public better understand how asymptomatic carriers can drive spread of the disease. Ompad points out, it’s another reason to keep wearing a mask in public.

Ompad says it’s important that doctors explain what antibody test results mean. People who decide to get tested for antibodies should ask their providers questions to make sure they understand their results.

“You have to help people understand the meaning of the test, what the results mean, what you’re being tested for. That should be happening so people understand,” she says.

It can be a challenging and frustrating process for people to stay up to date as knowledge about COVID-19 grows and changes. It’s also true that learning over time is par for the course with the emergence of any new infectious disease. Continuing to learn about a new disease over time is critical for the public health response, including limiting transmission from person to person as much as possible.

“We’ve only known about this disease since December and it wasn’t declared a pandemic until March,” says Ompad. “The public finds it frustrating when we say one thing and the knowledge changes. I want to make it clear: It’s not because we don’t know what we are doing.”

Nicole Javorsky is a Report for America corps member.