Abigail Savitch-Lew

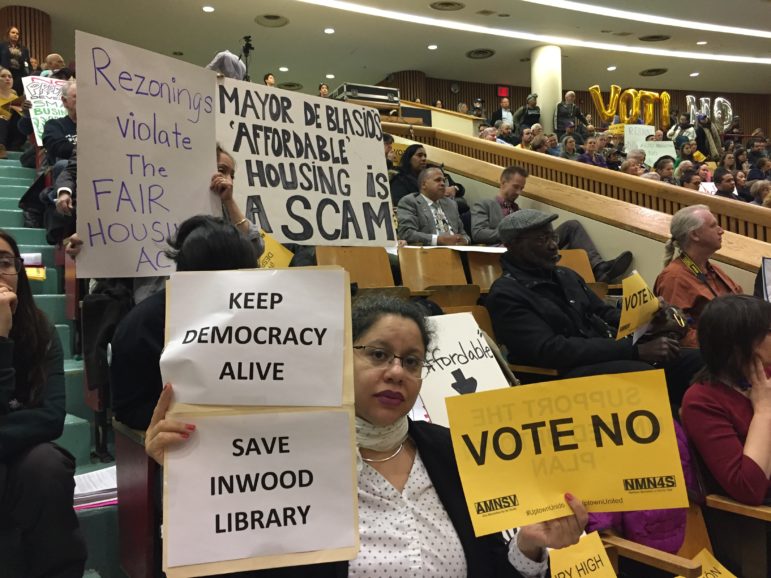

Protesters at Borough President Gale Brewer’s hearing on the Inwood rezoning on April 10, 2018.The de Blasio administration and the Inwood activists who sued it now await an appeals’ courts decision on whether a rezoning will stand–a ruling that could set important precedent for New York City land-use policy for years to come.

A coalition of advocates from Northern Manhattan Is Not for Sale, individual business owners and residents sued to annul the 2018 rezoning, arguing the city had failed to complete an adequate environmental review. Last December, a lower court agreed with them, and annulled the City Council’s approval of the rezoning.

Last week, the city’s Law Department and the attorney for the coalition went before the Appellate Division to argue over the de Blasio administration’s appeal of that ruling.

City defends not addressing racial impact

The city’s Law Department attorney, Scott Schorr argued the city had met every criteria required by the city’s environmental review process in order for the rezoning to qualify for City Planning Commission and City Council approval.

“The Supreme Court applied the wrong standards to the city’s environmental review,” said Schorr at the start of his argument, arguing that the law “affords agencies room to exercise their discretion about which impacts to analyze, how to analyze them, how deeply to analyze them and how to make numerous line-drawing decisions.”

Justice Rosalyn Richter, the one of five justices listening to the appeal argument, interrupted for a moment and stated, “The fact that the city’s analysis does not break any of this information down to explore the impact on racial and ethnic groups [is] an issue that certainly is of concern to some of the [justices] here.”

Schorr agreed the issue of the impact on racial and ethnic groups was of “substantial concern” but he said the environmental impact statement (EIS) produced by the city did address the closely related question of residential displacement. It projected there would be no significant adverse residential displacement of low income residents in the rezoning–largely because the rezoning would have added housing, including permanently affordable housing, to the area.

“We’re looking at about over 4,000 new housing units, about a quarter of which will be permanently affordable, and once the determination was made that there was not going to be an adverse displacement effect for residential use, it didn’t make a particular sense to demand that the city go further and do a racial-impact analysis,” he contended.

The attorney for the coalition who sued to overturn the rezoning, Michael Sussman, argued the city had “repeatedly failed” Inwood and have refused to meet the community’s demand for an EIS that included a racial impact study component as part of the larger conversation on racism in the city.

“They have been dead wrong repeatedly on this critical issue, leading to segregation in the city. That’s the ultimate issue here. We’re trying to create one city with some degree of equitability and equity for people. That is what is not happening because they refused to open their eyes and study it,” said Sussman, a civil rights attorney.

Sussman additionally said the city sold the rezoning to the Inwood community under the guise of affordable housing and called the term “deceptive” in this case because those affordable housing units would not meet the income levels of the current Inwood residents.

Approved, then annulled

The Inwood rezoning was approved by the City Council in August 2018, and was slated to bring residential and commercial development eastward across 10th Avenue to the Harlem River, while applying contextual zoning —to preserve neighborhood character—to several residential areas west of 10th Avenue.

The estimated $500 million rezoning plan would have facilitated 2,600 new affordable housing units under the mandatory inclusionary housing (MIH) program and preserved another 2,500 existing affordable homes, according to the city. It included a plan to replace the Inwood library with a new residential building which would sit atop a new library.

But Inwood community groups like Northern Manhattan is Not for Sale have accused city officials of having sold out the community, saying residents did not want the rezoning as it stood: without a racial impact study documenting possible racial displacement of residents and businesses. Before the plan was approved, Inwood community members and organizations held several protests against it, including one incident where some protesters were arrested after taking over local Councilmember Ydanis Rodriguez’s office.

The lawsuit argued the city’s environmental review process failed to examine how the rezoning would impact the demographics of the Inwood community, residential displacement, women- and minority-owned businesses, emergency response times and speculative real-estate activity as well as the cumulative impact of the rezoning and other nearby land-use moves. Those issues were raised during the review process by United Inwood, a constituent group within Northern Manhattan is Not for Sale.

A process under scrutiny

For most major land-use actions, such as city-initiated rezonings, there has to be an environmental analysis and Environmental Impact Statement (EIS), a document analyzing the potential impacts of a land use change. The Department of City Planning (DCP) must release a draft EIS before it can launch the Uniform Land Use Review Procedure (ULURP), the multi-step public review process required to legalize a land-use change. DCP’s predictions are based on an assessment of development trends and other factors.

If the Appellate Court makes a ruling in the favor of the city, the rezoning will move forward as was planned when it was approved by the City Council. If the ruling is in favor of the Inwood lawsuit, then the city would have to revoke the rezoning action and start over. The neighborhood could lose the funding towards capital investments promised during negotiations with Rodriguez before the plan passed.

Inwood was the sixth neighborhood rezoning approved during the de Blasio era; others occurred in East New York in Brooklyn, Downtown Far Rockaway in Queens, East Harlem, Bay Street in Staten Island and Jerome Avenue in the Bronx. The city had hoped to rezone Bushwick in Brooklyn and Southern Boulevard in the Bronx, but those have been shelved. A possible rezoning in Gowanus is pending.

Future mayors, however, could pursue rezonings elsewhere, and the Inwood case could bear on how the environmental reviews are conducted in all future cases.

Housing and tenant advocacy groups and elected officials have asked the city administration to show support for legislation requiring that each EIS include a racial-impact study. That bill was introduced by Public Advocate Jumaane Williams and co-sponsored by Bronx Councilmember Rafael Salamanca last year in December.

At the same time, the de Blasio administration has warned that the Inwood court case could bog down land-use decision making.

“During oral argument on Wednesday, the City’s counsel noted that the environmental review process would grind to a halt if every public comment triggered an obligation to conduct further substantive review of potential environmental impacts,” said a Law Department spokesperson in an email statement to City Limits.

Developers are also opposed to expanding the EIS process. “If last year’s misguided decision is upheld, it will severely impede affordable housing creation citywide at a moment when adding affordable housing couldn’t be more critical,” said statement to City Limits from Taconic Partners, a developer involved in one Inwood project. “If the judge’s decision stands, they’ll all go away – and neighborhoods across the city will miss out on similar investment opportunities for years to come.”

Inwood is not alone

To the south of Inwood and across the East River in Flushing, just a few days before the Inwood appeal case came up for argument, a coalition of community groups filed a lawsuit against the Department of City Planning and the City Planning Commission over a proposed waterfront development facilitated by the city, state and Flushing Willets Point Corona Local Development Corporation.

The coalition includes Chhaya Community Development Corporation, MinKwon Center for Community Action, the Greater Flushing Chamber of Commerce, and local activist Robert Loscalzo.

The lawsuit alleges the city must pursue an environmental review process before it approves this development.

According to the lawsuit, the city was wrong to give the proposed waterfront development plan a negative declaration–meaning there would not be a significant impact on the environment as a result of the project, and no detailed EIS is needed.

The coalition found that decision odd, since the administration had foreseen multiple impacts when it considered a broader Flushing rezoning in 2015. That proposal was ultimately withdrawn. The current Flushing Waterfront Revitalization Plan covers a portion of the city’s abandoned Flushing West rezoning plan.

The Flushing rezoning plan would have applied to an 11-block area east of Flushing Creek and west of Flushing Prince Street. The group behind the current plan is FWRA LLC, a partnership of three private developers who own the majority of property along the waterfront. The plan is slated to create a 29-acre waterfront special district for nine buildings, including 1,725 new apartments, a hotel, a new road system, public open space on the waterfront, commercial space for retail and offices and a community center space.

During the online zoom press conference announcing the lawsuit, MinKwon Executive Director John Park said the decision to forego an EIS was baffling since they had done ground work with the community that reflected a different story in a survey MinKown conducted in 2015.

“The top concern of local residents, at 74 percent, was lack of affordable housing, with 28 percent concerned for neighbors being displaced at that time,” said Park.

The proposed rezoning is now in the midst of the ULURP process. So far, Queens Community Board 7 approved the rezoning 30-8 despite opposition from community groups and residents in February. However interim Queens Borough President Sharon Lee recommended against approval of a development plan for the Flushing waterfront in an advisory opinion in mid-March. In her recommendations, Lee said there was potential in the plan to create a waterfront district, but the potential for adverse impacts was too great. “The people living closely to the SFWD will bear the brunt of the noise, dust, traffic and other construction-related inconveniences as the proposed project is built, with little chance to afford or secure some of the new housing that would be built in the new modern waterfront development.”

Lee’s conditions for approval included a commitment to paying prevailing wages, hiring union labor and building more affordable housing, and new school seats in downtown Flushing.

Typically, the next step takes place at the City Planning Commission which would have 60 days to vote on the proposal. Then in City Council the proposal is reviewed by the Landmarks, Planning or Zoning subcommittee and then the full Land Use Committee before the entire City Council can consider a proposal and later a vote. By tradition, the Council usually follows the lead of the councilmember in whose district a project falls.

Further action has been on hold due to the Coronavirus epidemic. In mid-March, Mayor Bill de Blasio issued an emergency order that froze all land-use review processes in order to avoid the public gatherings that are part and parcel of those reviews.

The Flushing plaintiffs say the City Planning Commission (CPC) and the City Council plan to act on it as soon as both decision-making bodies are able to meet virtually.

The City Council began remote video meetings and hearings on April 24. CPC has released no details on how the Commission will resume ULURP processes as the city starts to reopen.