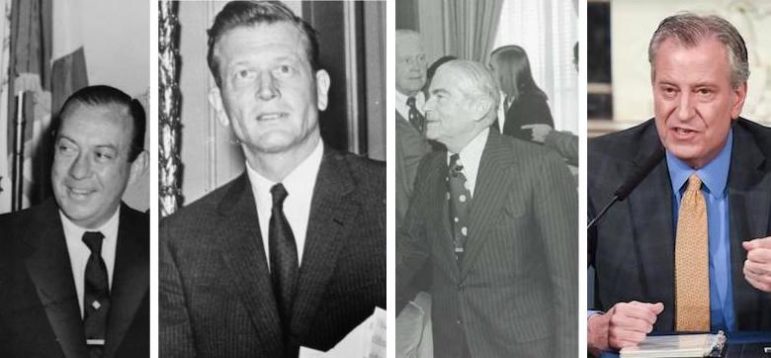

Walter Albertin/World-Telegram & Sun; photographer, Orlando Fernandez/World-Telegram, Carl Albert Archives, Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office

Ever since borrowing by Mayors Wagner, Lindsay and Beame preceded the Fiscal Crisis, mayors have avoided issuing IOUs for operations. But Mayor de Blasio is facing a deeper, sharper budget gap than his predecessors.Over the four decades since New York City’s fiscal crisis, one article of faith has achieved the status of a civic Commandment: The city must never, ever do what Mayors Wagner, Lindsay and Beame did and borrow to pay for operational expenses.

The COVID-19 fiscal crisis has changed much about life in the city. Might it also weaken the prohibition against IOUs? Councilmember Helen Rosenthal, a member of the Council’s budget negotiating team who is running for city comptroller in 2021, thinks it should.

Rosenthal told WBAI’s Max & Murphy Show on Wednesday that the city’s budget shortfall is expected to be $14 billion. “There are only two guaranteed options in this situation given that the state controls taxing (so, taxing is not an option for the city): We can cut programs and tap into our reserves,” she said. “There is another option that the city should not shy away from and that is borrowing money. Now, this requires state approval and that’s super challenging and everyone seems to gasp whenever I bring it up or I hear others bring it up in budget meetings. I don’t think we should write that off as impossible.”

Helen Rosenthal on the Budget, Bad Cuts and Borrowing

Borrowing would be an extraordinary measure, but these are extraordinary times. James Parrott, an economist at the Center for New York City Affairs, told Max & Murphy that his estimate of 1.2 million jobs lost places the current economic crisis ahead of any others the city has suffered since the Second World War. “This is beyond the worst that we saw in the Great Recession in 2008, worse than after 9/11, worse than the 1990’s recession,” he said. “The magnitude of it is greater than the hemorrhaging both in population and in jobs that the New York economy suffered during the 1970s. This makes it worse than any period since the Great Depression.”

Over the first six weeks of the crisis, 624,277 New York City residents applied for unemployment insurance, compared with 31,328 over the same period last year. Parrott believes that’s a lagging indicator. “We know that there has been a tremendous backlog for people seeking to apply for unemployment in New York State. The volume and speed with which the job losses occurred swamped labor departments all across the country,” he said. Plus, “200,000 undocumented workers lost work and aren’t eligible for UI claims so they’re not included in those numbers.”

James Parrott on the Depths of NYC’s Job Losses

New York City borrows regularly, but that money is for capital expenses, not operations. In 2019, the city carried $89 billion in debt, according to the Independent Budget Office—about $10 billion more than in 2014, the year Mayor de Blasio took office. Serving that debt is expected to cost $5.6 billion this fiscal year – about as much as the city will spend on the NYPD.

New borrowing would add to that debt burden and the cost of servicing it each year. Rosenthal’s argument isn’t that this represents an attractive option, but that it is worth considering among a menu of unalluring choices.

“The current crisis is not going to be solved by the same approaches. When you look at the budget, you can’t simply cut a way out of the deficit. The hole is just too big and an austerity budget would aggravate rather than solve the enormous problems we’re facing. We are going need to make the most intelligent cuts possible and look at the macroeconomic solutions which involve more government spending. We have to build back in such a way to begin to address the economic disparities that have already existed.”

“I would argue we’re in a crisis,” she added. “We should borrow money to pay for incredibly important things we need to fund now.”

Mayor de Blasio has proposed taking about $4 billion out of reserves to close this year’s budget gap. Rosenthal said she would prefer the city take $3 billion from reserves to retain more in the rainy-day fund should things get even worse. “I would work harder to find more productivity and savings in the city budget,” she said, although she also criticized the savings de Blasio has identified, especially cuts to summer youth employment and to job training.

Both Rosenthal and Parrott said the need for more federal involvement was paramount. The stimulus so far, Parrott said, has been minimal. “I wouldn’t call it a stimulus although that’s the way they’re often referred to, it’s sort of an emergency economic assistance to maintain earnings and to maintain businesses. We’re not at the point of stimulating the economy to get back to where we were,” he said. “It’s a matter of keeping the economy from contracting to a greater extent than it already has.”

“Even under the best of circumstances, in New York City, we’re going to see the loss of 200,000 to 400,000 jobs by the end of the year. Hopefully, we’ll get a lot of the jobs, where people are now not working, back but restaurants are not going to come back,” he added. “Broadway is not going to come back. Movie theaters and a lot of the social activities in New York City are not going to return anytime soon. That’s going to leave us with a significant hole in the economy. That’s going to be so significant that there will have to be more federal government response.”

2 thoughts on “It’s Worse Than You Think Out There. Maybe Bad Enough for NYC to Borrow to Pay the Bills.”

Diogenes is still searching for someone honest in Washington after passage of the most recent $484 billion Corona Virus relief bill. This is the fourth one passed by Congress and signed by the President in the past two months. They total $3 trillion in borrowed money. What about our federal $23 trillion long term debt projected to grow $1 trillion more annually until 2030? We just added another $3 trillion on top of that. Some want ever more! Who is going to bail out Washington? Only government can get away with maxing out its credit cards with no consequences. Sooner or later China and other creditors are going to call in the bill. You can’t continue spending money you don’t have forever.

All levels of government and the private sector must make difficult financial decisions on how to use existing resources. Americans prioritize their own family budgets. They make the difficult choices in how existing resources will be spent. If it can wait till later, it should be postponed.

Shouldn’t the President and Congress find the courage to offset some of these costs by reducing expenditures within the current $4.8 trillion budget? We must freeze future federal spending levels in coming years. This would provide a down payment in paying off this debt.

Larry Penner

Here’s a couple of ways to save money:

1. Get rid of the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation

2. Get rid of the Harlem Development Corporation

3. Get rid of UMEZ

4. Get rid of NYC & Company the alleged tourism agency

5. Get rid of Bronx Economic Development agency

All these suedo agencies/corporations have bloated salaries with staff who do nothing.