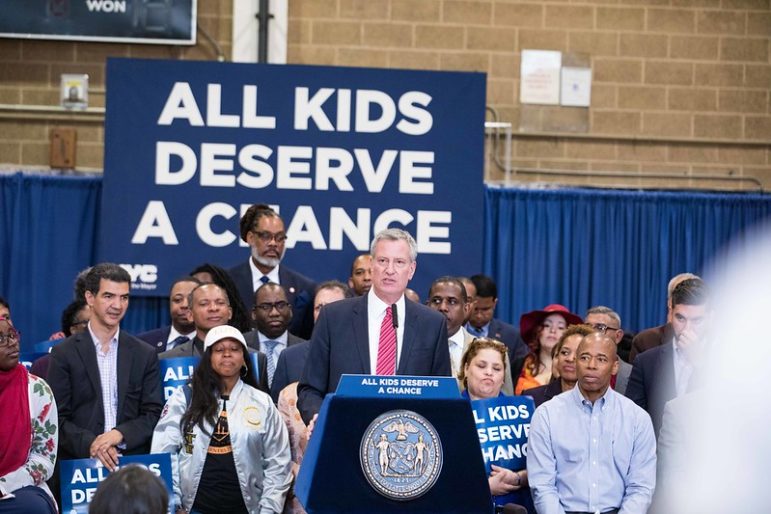

Benjamin Kanter/Mayoral Photo Office

Mayor de Blasio at J.H.S. 292 in Brooklyn in June, 2018.As the coronavirus pandemic reveals how systemic inequality puts minority groups at risk across the board, disparities in education can’t be overlooked. It is evident that high-needs schools in underserved communities are less equipped for a learning disruption than their wealthier counterparts.

The schools struggling to adapt to remote learning overlap with neighborhoods bearing the brunt of coronavirus’ blow, and a clear picture of the “haves” and “have nots” has come into focus.

One of the hardest hit neighborhoods in NYC is in the south Bronx, where the confirmed cases are 37 percent greater than the city average. The Upper West Side in Manhattan is starkly different: the confirmed cases are 44 percent less than the city average. These numbers demonstrate how wealthier families are able to work from home and avoid falling ill. Many families in poorer districts, like those in hard-hit Jackson Heights, Queens and Brownsville, Brooklyn, don’t have that luxury. As caretakers in underserved communities continue to leave home for work and contract the virus, students are left to learn remotely without as much supervision and guidance.

In a school district on the Upper West Side, 77 percent of students were proficient in English Language Arts by third grade this time last year. In a district in the Bronx, that number is nearly half: only 43 percent of students were testing proficient. Students in low-income neighborhoods already face inequities when it comes to learning because of poor funding, teacher shortages and high teacher turnover rates. Add a public health crisis and a new learning environment that favors the well-resourced. It’s easy to see how the opportunity gap is exacerbated.

City Hall recently announced $262 million in Department of Education (DOE) budget cuts as a result of coronavirus. $100 million of that will come from the “fair student funding” formula, which was designed to funnel more money to the highest-need schools. Another $121 million will be cut from professional development spending. This is devastating and a further disadvantage for schools that were struggling before a pandemic. Combined with the concentrated impact of the virus on low-income families, it’s crippling.

My nonprofit, Teaching Matters, typically works to support and train teachers in high-needs school districts. When Mayor de Blasio made the call to close schools, we shifted our model to content creation. We are churning out curriculum for every single day students learn remotely and prioritizing creating materials that are low-tech and viewable on a phone in case students don’t have a computer at home. The materials are reaching the children of doctors, nurses, grocery-store employees, along with many other frontline workers who cannot stay home to help their kids with distance learning.

CityViews are readers’ opinions, not those of City Limits. Add your voice today!

CityViews are readers’ opinions, not those of City Limits. Add your voice today!

Whether or not remote learning is extended through the summer, teachers need to be supported and prepared right now. They need to be equipped with all tools necessary to effectively teach students in this unprecedented environment. We made modules and webinars for teachers of English language learners and opened a chat line on our website to field questions.

To be sure, Schools Chancellor Richard Carranza’s focus has been making the public education system more equitable, and the Department of Education has done excellent work transitioning the nation’s largest school district to remote learning. The purchasing and distribution of 300,000 laptops to homeless students across the city was an integral step in closing the digital divide. The implementation of a grab-and-go meal system was essential for many kids who rely on school lunches or whose parents are still working and can’t provide them. Still, we must not dismiss the stark reality this pandemic revealed.

Coronavirus is shining a bright light on the stark inequalities that plagued all avenues of society well before the pandemic overtook our city. As the disadvantages of remote learning in low-income areas continue to compound with high rates of confirmed Covid-19 cases, we must look at how our city has been structured to benefit some students and their families over others.

Let’s use this as an opportunity to prioritize education and resist budget cuts that will greatly impact our city’s most vulnerable children.

Lynette Guastaferro is the CEO of Teaching Matters, a nonprofit that increases teacher effectiveness to improve student success.