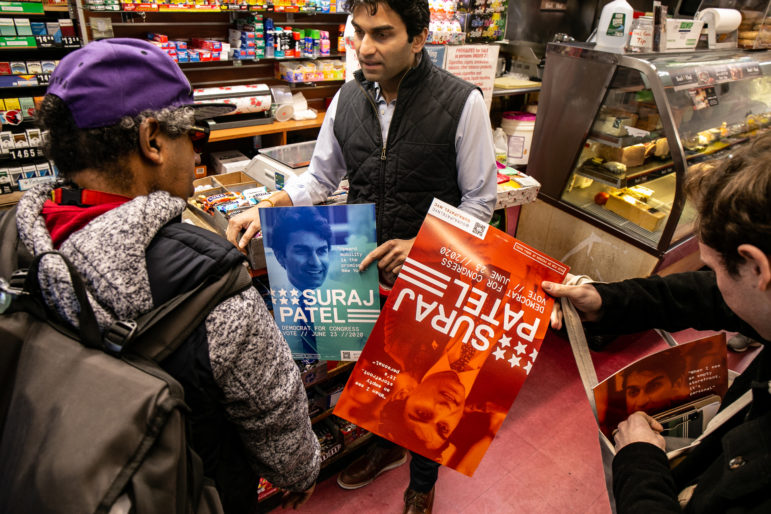

Adi Talwar

On a recent February Monday morning, Suraj Patel canvassing at a Deli on the corner of Avenue B and 10th Street in the East Village.Child poverty shames the United States. The richest country in the world counts one in five of its children as poor, the 10th highest rate among the 36 members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. The phenomenon is as costly to society as it is cruel to kids, translating into higher crime rates, a less productive workforce, steeper healthcare costs, and other expenses.

The problem is especially acute in some of New York City’s Congressional districts, like the area represented by outgoing Rep. Jose Serrano in the Bronx, where half of kids are poor, or Rep. Nydia Velazquez’s Lower East Side-Brooklyn-Queens district, where more than a third are.

In the 12th District, represented since 1993 by Democrat Carolyn Maloney, child poverty is not as prominent: About 11 percent of kids in the district—which straddles the East River in linking Manhattan, Brooklyn and Queens—are poor, significantly less than the national average.

But child poverty is what Suraj Patel, the 36-year-old lawyer and organizer mounting a second challenge to Maloney, has built his first major policy proposal around, declaring: “Eliminating child poverty is not only an economic but a moral imperative.”

He’s proposing that the current alphabet soup of complicated tax breaks for parents—like the Child Tax Credit and the Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit, along with part of the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC)—be collapsed into a single, universal “child allowance” that would give every family, regardless of whether they owed taxes or not and irrespective of how high their income is, a monthly $500 credit per child five-years-old and younger and $350 for each kid aged 6 to 17.

Halving child poverty?

In a policy paper, Patel’s campaign contends that this allowance will cut U.S. child poverty by more than half, from 12.2 million kids to about 4.8 million. The paper argues that the existing credits suffer from inefficiencies:

All of these benefits are phased in, meaning the beneficiary must have a minimum income to receive them. Many individuals living in poverty do not earn an income for various reasons, so the current structure often ignores the needs of the most impoverished. Furthermore, these tax credits are paid out once a year and only the EITC is fully refundable, meaning that if the credit is greater than the amount of taxes owed, the difference is paid as a refund. … Finally, these credits are paid out once a year as opposed to monthly. This particularly harms families living on tight budgets who would greatly benefit from additional monthly income to cover expenses such as housing and groceries. These tax credits also phase-out as income increases. The biggest unintended consequence of phase outs is when individuals start to forego income to keep their benefits or choose to work off of the books.

Patel also criticizes other elements of the current social safety net for children as having been captured by private interests. For instance, mothers using the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) in New York “cannot buy reduced fat milk, flavored yogurt, canned baked beans, or peanut butter with added minerals like heart healthy Omega-3 fatty acids.” A simple cash benefit would give families the ability to make their own choices on food and other purchases, he contends.

Patel’s plan doesn’t call for ending WIC or the other major non-cash benefit for families, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), formerly known as Food Stamps. But he anticipates use of those programs will decrease once his plan begins changing the fortunes of low-income families.

In an interview, Patel says the universal credit addresses two quirks in the way child-rearing and family economics match up. “One imbalance in our economy is that raising a child is work. It’s just that no money is transacted. It’s like we say to a mom, ‘You’re not getting rewarded for the work your doing in the economy, but we do need it because we need children to grow up and become part of the workforce.’” The universal credit, he says, “is compensating for that.”

A second imbalance, Patel continues, is that by and large, 20- to 40-years-olds has children—and that’s a time in the average life when earnings are relatively low. “By providing some money in the pockets of young families you have massive growth effects down the line,” he says. “For every dollar spent on children you’re getting $7 back in the form of everything from better test scores to lower incarceration rates and less illness.”

Lamenting that only 10 percent of the federal budget is spent directly on children, Patel is also calling for nationwide universal pre-K for three- and four-year-olds, up to 12 weeks of paid family leave, a federal-state “public option” for child care in each state and “Medicare for Kids” to provide health insurance to four million children who currently lack it.

His campaign can’t say what the full price-tag for the bundle of programs would be but Patel estimates that the universal child allowance would require $350 billion a year—an amount that would mostly be funded by ending the current tax credits. (Canada did something similar beginning in 2016, and it is credited with achieving a reduction in child poverty.)

A delicate dance

The proposal represents a delicate dance for Patel, who two years ago mounted the stiffest challenge Maloney has ever faced in a Democratic primary, nabbing 40 percent of the vote.

In 2018, Patel fully displayed the mien of a progressive insurgent, calling for the defunding of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), emphasizing his support for Black Lives Matter and stating his belief in gender as a spectrum. Patel actually bested Maloney in the Brooklyn part of the district and basically tied her in Queens. The problem was, three quarters of the district’s voters are in Manhattan, where Maloney won by a roughly 2:1 margin.

This year, with a mostly new campaign staff, Patel is taking a different approach, seeking to differentiate himself from Maloney less on ideological grounds and more on what he says is a contrast in the energy and ideas he brings to the table. His emphasis is on wonky plans for improving bread-and-butter conditions, not bold calls for resetting the social order.

For instance, his campaign website’s policy section revolves around an “upward mobility agenda” that emphasizes opportunity rather than redistribution—although the agenda incorporates many a progressive touchstone, from tackling climate change to ending mass incarceration, fixing the immigration system and bucking corporate power.

Patel’s new family policy agenda reflects these new nuances. In a report accompanying the proposal, Patel highlights income inequality, noting that the 12th district displays a high Gini coefficient–a common measure of income polarization. But his keystone policy idea, the universal child allowance, is not primarily a tool for redistribution, he notes. Instead, it’s about distribution: Everyone with kids gets the benefit, regardless of income.

Patel says this will avoid the problem of benefit cliffs, where earning an extra dollar in salary can mean a massive loss of income support. He also believes universal programs, like Social Security, enjoy broader political support than means-tested programs, insulating them from cuts or cancellation.

The flip-side, of course, is that universal programs cost a lot more money than targeted ones, and they spend some of that money on benefits to very rich people who, it might be argued, don’t really need it. And if inequality is a problem worth highlighting, universal benefits do little to directly combat it. The bet instead is that, by making everyone a little richer, the policy equips the people at the bottom to compete and close the income gap themselves.

Issues and IOUs

Aside from questions about the policy, the doubt Patel will face is whether a rookie member of Congress—which is what he will be if he wins the June primary and the November general election—would be able to achieve a major shift in federal policy like the universal child allowance.

Maloney is serving in her 14th Congress; only five of them have had Democratic control, constraining her ability to get legislation passed. Still, her official bio lays claim to successful passage of 70 pieces of legislation over time. These include the Zadroga Act for people sickened by working at Ground Zero, and the CARD Act, which regulated the credit card industry, likely saving consumers billions. Early in her career, she focused on some of the same issues Patel is now highlighting: After giving birth while a member of the City Council, she in 1988 introduced a suite of bills to create more day-care resources in the city.

Among the laws Maloney—who is the Chairwoman of of the House Committee on Oversight and Reform—drafted during the current Congress is the PUMP for Nursing Mothers Act, the Family Medical Leave Modernization Act and the Federal Employee Paid Leave Act. Her campaign platform calls for universal pre-K, exploring universal paid leave and passing Medicare for All. This week she held hearings in Washington to “put a national spotlight on some of the Trump administration’s most harmful policies: those that will increase child hunger and homelessness, erode standards on toxic mercury, and make onerous changes to the poverty line calculation,” according to her campaign.

“Never before has our country seen such an assault on social programs meant to help our most vulnerable, including children,” a Maloney spokesman said, calling the Congresswoman “most prolific legislators in Congress.”

That résumé illustrates that by emphasizing child-care and child-related tax benefits, Patel is seeking a debate on what for Maloney is familiar territory. He’s also laid down a marker on what, partly by virtue of male candidates’ neglect, are typically issues championed by female candidates, and the 12th district primary race features three of those.

Besides Maloney, Erica Vladimer, the leader of an effort to create accountability for sexual misconduct in the state legislature, and comedian/advocate Laura Ashcraft are also in the field. Vladimer’s extensive platform includes a call for paid family leave and free childcare, as well as a commitment to forgive student loans. Ashcraft also calls for universal child-care; her agenda also champions housing to be treated as a human right and the decriminalization of sex work. Peter Harrison is also in the race, emphasizing transit issues.

Turnout in the 2018 primary was about 15 percent. It’s unclear whether that’s the new normal, or whether the energy of 2020 will spike interest further. It’s even less clear whether more turnout helps or hurts the challenger. Maloney could be better prepared to counter this time. Or Patel might benefit from the name recognition that comes with a second bid.

The Congresswoman, who has loaned $100,000 to this year’s campaign, has booked $1.4 million in contributions. But after heavy spending she has about $324,000 in the bank, slightly less than Patel, who has raised significantly less (about $486,000) but spent stingily; he reported $345,000 on hand as of December 31. Ashcraft had $47,000, Harrison $13,000 and Vladimer roughly $12,000 in the bank at last report. No Republicans have begun raising money in the district so far, according to Federal Election Commission records.

Patel has loaned this year’s campaign $10,000. His 2018 campaign, which he converted into a PAC called New Electorate that aimed to support other upstart candidates around the country, never actually pursued that mission. It carries a debt of $355,000. Patel says he is the sole holder of those IOUs, and does not anticipate retiring that debt.