The latest data release from the Census Bureau reinforces positive trends for New York City’s families and children. In 2018, the median household income for families with children in NYC increased almost 10%, equivalent to more than $5,000. Alongside this increase, poverty for all New Yorkers and specifically children decreased 0.7 and 1.4 percentage points, respectively. Children in New York City remained insured at higher rates than the rest of New York State and the U.S. broadly, and the share of insured children held steady despite a decrease in child insurance coverage countrywide.

While overall measures of well-being are moving in the right direction, families and communities who have faced long-standing discrimination, criminalization, and disinvestment continue to experience higher rates of poverty. For this reason, Citizens’ Committee for Children recently published a factsheet of the latest Census data with a focus on New York City’s single parents and their children. The data highlight how the economic insecurity of single parents and their children is widespread and compounded by neighborhood poverty, as well as gender and race inequity.

Currently, the number of single-parent households is on the decline. Still, as they remain a sizable share of the homes where children live, there’s more that can be done to support the well-being of single-parent families.

The multifaceted challenges of being a single parent

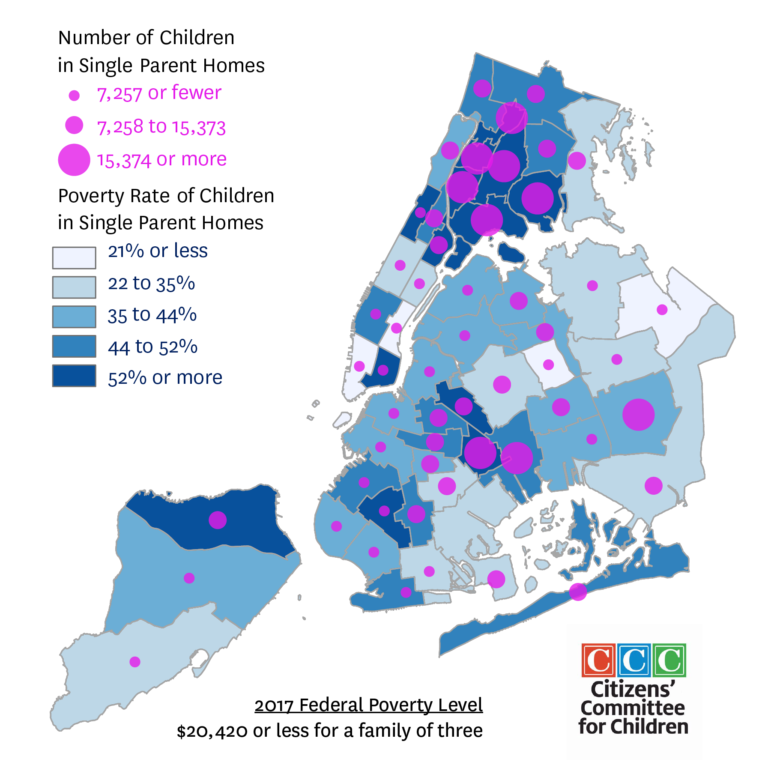

Single-parent households are the second largest household type in New York City and were home to more than 425,000 children in 2018. The experiences of single parents and their children, therefore, are not uniform across the city. Areas where there are more children in single-parent households tend to see higher rates of poverty among those children. At the same time, concentrated neighborhood poverty can heighten economic insecurity even in areas with relatively fewer children of single parents. This is the case in places like Borough Park in Brooklyn, as well as the Lower East Side and Manhattanville in Manhattan – all of which see poverty rates above 50 percent for children of single parents. These geographic trends (see the map above) suggest neighborhood conditions and household structure should be examined together to understand the landscape of child poverty.

Nationally, labor-force participation and employment are on the rise among single parents – especially single mothers. This is observed among New York City’s single parents as well. From 2013 to 2017, the share of single parents active in the labor force (either employed or looking for work, aged 16 and over) increased seven percentage points; during the same period, single parents’ unemployment rate fell from 26 to 16 percent.

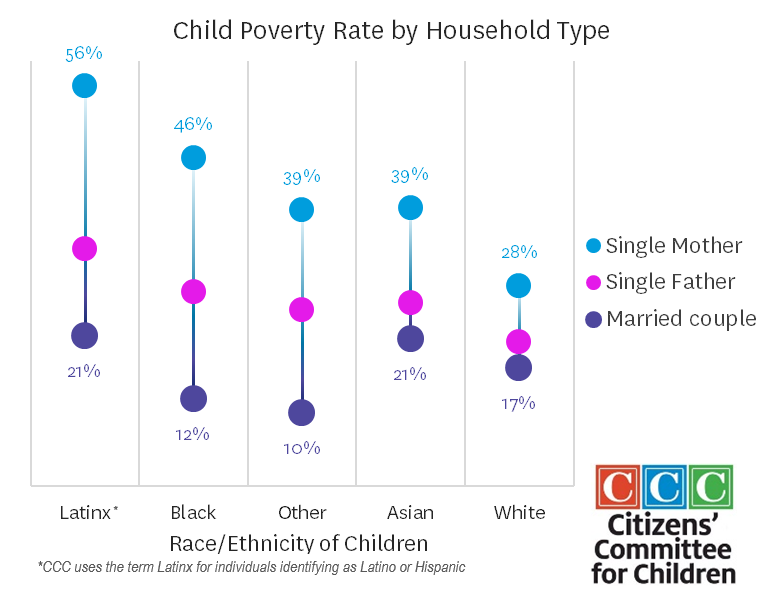

Despite this positive development, deep inequalities persist. Married couples may benefit from two potential income-earners providing for their children, while single parents are often supporting kids on their own. This disadvantage is compounded by the social and economic inequities that pervade the labor market, widening income gaps across race and gender. In New York City, Black and Latino children of single mothers experience poverty rates of 46 and 56 percent, respectively. This is almost three times the poverty rate for Black and Latino children of married couples; it is also double the rate of poverty for White children of single mothers (28 percent).

A history of punishing single mothers

The role of family structure in shaping child development has been the subject of policy and research scrutiny for over half a century. Single motherhood has specifically been pathologized, going back to the Moynihan Report in 1965, as the primary reason for higher poverty rates in the African American community. It was this framework that propelled national lawmakers to “end welfare as we know it” in the 1990s, radically restricting single mothers’ access to safety net programs like Temporary Aid to Needy Families (TANF). Local government administrations nationwide, including New York City, followed a ‘welfare-to-work’ approach—making access to public benefits contingent on parents’ active employment.

The lessons of this history and findings from recent research lead us in a different direction. A cross-national study published in 2017 examined the effects of different risk factors on poverty rates and concluded that “single motherhood may be the least important of the risks,” even estimating that an increase in the prevalence of single mother households would result in a modest decline in the overall poverty rate. That is to say that single mothers, or single parents more broadly, are not the reason for child poverty, and should not be penalized as such.

Defending the safety net in times of austerity and uncertainty

In light of deep-rooted inequities, protecting the existing safety net is essential to providing single parents and their children with access to healthy food, health care, housing, and education. Programs like WIC, SNAP, and federal housing subsidies play a vital role in lifting children out of poverty; research shows that the anti-poverty effects of these programs are even greater for single-parent households. Presently, the Trump administration is threatening to cut SNAP access for three million recipients nationwide by eliminating states’ discretion in determining eligibility thresholds. This is only the latest in a sequence of attacks on low-income and immigrant families – including shrinking the federal poverty threshold to curtail eligibility for programs like Medicaid and Head Start, and potentially evicting thousands of family members who belong to mixed status households benefiting from rental assistance or public housing.

Many single parents, especially single parents of color, find themselves squarely in the crosshairs of these attacks, making it as important as ever to defend their access to the safety net. As federal policies perpetuate a ‘chilling effect’ to discourage the take-up of public benefits, it is incumbent upon organizations from the community level up to the city government to combat scare tactics and ensure that eligible single parents and their children continue to receive support.

It is also at the local level where city government can go beyond filling the gaps left by federal policy and innovate new strategies that inform the national conversation. Such was the case with the New York City’s Center for Economic Opportunity creation of a local alternative poverty measure informing the development of the national Supplemental Poverty Measure. Other examples include the local New York City Earned Income Tax Credit, expansion of Universal PreK to all four-year-olds or establishment of the $15 minimum wage, among others. These strategies put into practice locally inform policy conversations nationally. What is critical about each of these efforts is that they support all families with children, but especially single parents. This a measure of good child and family policy: when it works for families broadly, but especially those who face the greatest challenges.

Jack Mullan, Sophia Halkitis, and Bijan Kimiagar are research staff at Citizens’ Committee for Children of New York (CCC) which is home to data.cccnewyork.org, the most comprehensive database on child, family and community well-being in New York City.