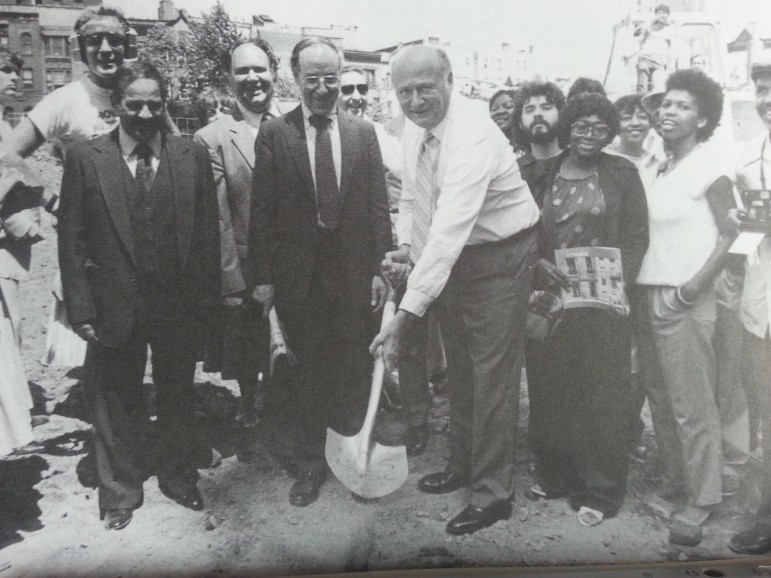

City Limits archives

The city’s whistleblower statute grew out of two executive orders by Mayor Koch.

First there was one whistleblower reporting on President Trump’s controversial telephone conversation with Ukranian President Volodymyr Zelensky. Then there were two. By the time the impeachment saga is over—if it ever is—we might learn of other figures whose role in the story will reference a 19th Century police officer’s whistle.

As Trump’s reaction to Whistleblower No. 1 illustrated, whistleblowers aren’t just people who cry foul about something they believe is wrong. Typically they also are people who have reason to fear that making such a complaint will expose them to retaliation, and therefore need protection. Since whistleblowing came to prominence in the 1960s, laws at the federal, state and local level have sought to maintain government accountability by protecting tipsters from retaliation.

For public employees in the city, that shield of protection is found in section 12-113 of the administrative code, headlined “Protection of sources of information.” It mandates that:

“No officer or employee of an agency of the city shall take an adverse personnel action with respect to another officer or employee in retaliation for his or her making a report of information concerning conduct which he or she knows or reasonably believes to involve corruption, criminal activity, conflict of interest, gross mismanagement or abuse of authority by another city officer or employee.”

The city’s whistleblower statute grew out of two executive orders by Mayor Koch. One, in 1978, imposed on city employees the “affirmative obligation” to report criminal activity or a conflict of interest “by another city officer or employee, which concerns his or her office or employment, or by persons dealing with the city.” A second mayoral order in 1984 extended that duty to allegations of gross mismanagement or abuse of authority. The whistleblower protections were added to the administration code that year. The statute was updated in 2012 to include employees of city contractors.

“The protections afforded by the Whistleblower Law are essential to maintaining a government that functions with integrity and transparency,” wrote then-Commissioner of Investigations Mark Peters in his letter to the Council last year. Peters was driven from his post by Mayor de Blasio a few months later.

Under the law, every year, the commissioner of investigation is required to report to the mayor and Council speaker on the number of whistleblower reports the Department of Investigation has received.

According to copies of those reports obtained via the Freedom of Information Law, DOI examines two or three dozen complaints for potential whistleblower protections each year. This is a small fraction of the 15,000 or so complaints DOI receives overall, and represents only those cases where someone expresses a fear of retaliation or alleges that it has already occurred, whether or not they declare themselves to be a “whistleblower.”

Agencies of Origin for Whistleblower Complaints, FY2014-FY2018

| 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | TOTAL | |

| Total | 36 | 36 | 28 | 40 | 30 | 170 |

| AGENCIES | ||||||

| Department of Education | 18 | 19 | 10 | 15 | 12 | 74 |

| New York City Housing Authority | 5 | 1 | 4 | 6 | 9 | 25 |

| Administration for Children’s Services | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 9 |

| Department of Correction | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 9 | |

| Department of Citywide Administrative Services | 4 | 2 | 2 | 8 | ||

| Department of Homeless Services | 2 | 4 | 1 | 7 | ||

| Department of Health and Human Services | 1 | 3 | 1 | 5 | ||

| Department of Housing Preservation and Development | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 | ||

| Health + Hospitals | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | ||

| Department of Parks and Recreation | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | ||

| Office of Payroll Administration | 1 | 2 | 3 | |||

| Department of Transportation | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | ||

| Human Resource Administration | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||

| Office of the Chief Medical Examiner | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||

| City Council | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Economic Development Corporation | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Fire Department | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Police Pension Fund | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Police Department | 1 | 1 | ||||

| CUNY | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Community Board | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Department of Finance | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Department of Youth and Community Development | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Department of Environmental Protection | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Department of Investigation | 1 | 1 |

It’s not a surprise that the Department of Education, easily the largest city agency with its headcount of 147,000, generated the most complaints: 74 over the five years. NYCHA was next with 25, followed by the Administration for Children’s Services and Department of Correction with nine apiece.

What is a surprise is that, of the 170 cases investigated over five years, only one qualified for whistleblower protection. That was a school-related case that closed in 2015.

Outcomes of Whistleblower Complaints, FY2014-FY2018

| 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | |

| Opened for investigation/preliminary investigations | 20 | 26 | 20 | 28 | 22 |

| No action/filed for intelligence purposes | 6 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 2 |

| Referred to another agency | 10 | 4 | 4 | 7 | 4 |

| Cases that remained open at year’s end | 12 | 16 | 9 | 18 | 12 |

| Whistleblower substantiated | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

If it seems odd to you that there’d be but one whistleblower over five years in a municipal bureaucracy with 300,000 employees and a budget of nearly $90 billion, consider this: Under the city’s law—as is the case elsewhere—the whistleblower’s report can’t be to just anyone. The report of wrongdoing must be made to the commissioner of investigations, public advocate or comptroller or a member of the City Council. Speaking to reporters—which many whistleblowers do and should continue to do (hint, hint)—doesn’t count.

Whatever the cause, the trend might be shifting. According to DOI, preliminary data for fiscal year 2019 (which ended June 30) indicate that five whistleblower complaints were substantiated: two involving schools and three concerning other agencies.

This could reflect a surge of wrongdoing. It could also reflect increasing awareness of the law: DOI conducted 449 whistleblower briefings in fiscal year 2019, the most in at least five years.

To be sure, someone doesn’t have to be declared a “whistleblower” to make a difference. DOI makes clear in its 2018 letter to the mayor and Council that, even in cases where a person is not officially labeled a whistleblower, DOI might still contact the agency to “redress any problematic conduct.”