Craig Hughes

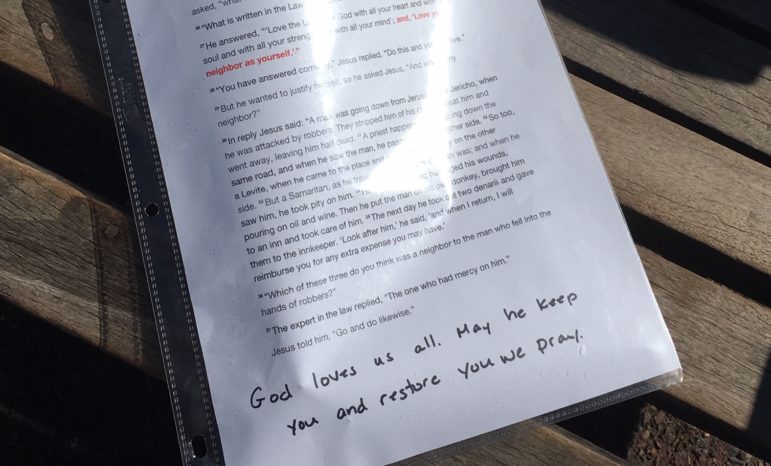

A note left at the makeshift memorial to the four men killed in Chinatown overnight Saturday.

The Saturday morning murders of four homeless men and critical assault on another is nothing short of tragic. The sheer violence of the attack is emotionally devastating. Media and politicians have largely reduced this to the actions of a “deranged” young person on a “rampage,” in a section of Chinatown that the New York Post describes as “overrun with ‘crazy,’ ‘rowdy’ homeless people”.

However, these killings should prompt us to face much larger issue. While the person who killed these four men is ultimately responsible for these deaths, an honest examination of what happened must consider larger contextual factors at play, which include a marked lack of truly affordable housing, useful mental health services, and easily accessible and appropriate shelter options. We also must confront the impacts of racialized and gendered NIMBYism often embraced by politicians and community members, institutionalized barriers to accessing supportive housing, and our collective reactionary impulse to support ‘out of sight, out of mind’ approaches to homelessness.

Violence, blame and banishment

A starting point in making much-needed changes would be acknowledging the violence homeless people face everyday — both the structural violence of being unable to access housing in such a wealthy city and the physical violence often inflicted by police and the public. The National Coalition for the Homeless estimated that 13,000 individuals in the U.S. die on the street each year, and conservatively estimated that in 2016 and 2017 there were at least 48 lethal attacks and 64 non-lethal attacks against homeless people in the U.S. Yet, the chronic assaults on homeless people are rarely seen for what they are: violence based on anti-homeless sentiments and discrimination. Take for example the quote in the New York Times’ lead piece on this weekend’s killings: “The motive appears to be, right now, just random attacks,” said Michael Baldassano, the chief of Manhattan South Detectives, “No one was targeted by race, age, or anything of that nature.”

But there was a common target: all were homeless and all were living on the street. They were also all men. While homeless men receive immense amounts of public blame for their very existence, we rarely talk about the high levels of violence they encounter.

Homeless men are often viewed as the most frightening members of the homeless population; they are dehumanized and viewed as a burden, and their proximity is portrayed as something we should all fear. State Senator John Liu, who helped lead a NIMBY effort to stop a shelter in Queens, shared this statement just last month: “From the outset, the residents of College Point have been unequivocal that a shelter for 200 single men would be wholly inappropriate for this residential site in close proximity to several schools.” Liu continued, “The community remained diligent, vigilant and united and has now successfully secured the conversion to a shelter for women, rather than single men. Although the plan is by no means perfect, we are satisfied that a far better outcome has been achieved.” Homeless men were just too scary for neighborhood residents, no evidence needed. The NYC Department of Homeless Services (DHS) gave into the irrational shelter panic, which will likely further bolster other NIMBY efforts.

It’s not hyperbole to say that the very existence of homeless men leads to calls of “don’t send them here!” and demands for – and offers of – more policing, by Democrats andRepublicans alike. (This is by no means intended to minimize the vast amounts of violence that women, youth and LGBTQI individuals face while homeless).

In July, Governor Cuomo wrote a letter to the MTA board explicitly blaming homeless New Yorkers for train delays. He stated, “I’ve never seen it this egregious, either on the numbers and on the statistics, or as a matter of visibility.” Soon enough, the MTA announced the addition 500 cops – estimated to cost over $100 million – tasked with patrolling the subway system, and launched a joint task force to study the matter. The recently completed task force report called for the MTA “to grow its police force by at least 50% to keep the transportation system safe and secure.” Policing needs to be expanded expressly because street homeless people are present.

Governor Cuomo isn’t alone in seeking the banishment of the homeless via increased policing. Under the De Blasio administration, New York City’s municipal outreach teams, police and sanitation workers have been tasked with dismantling encampments. Outreach workers have been provided grossly insufficient resources in the way of housing options for the homeless they are tasked with displacing. The reality is that due to an extreme shortage of truly affordable housing, failings at city shelters, inadequate supply of supportive housing, and cherry-picking by supportive housing providers, homeless encampments continue to exist because for many they are perceived as the safest way to survive. Although murders are very rare in shelters, and killings like those that happened on Saturday are unheard of, people’s negative experiences in shelters often lead them to the streets; when there they need support, not further forced displacement.

It is as though we have accepted the fact that people are forced to live and sleep on the streets in one of the wealthiest cities in the world, but simultaneously can’t tolerate seeing them. Consider Cuomo’s comment about “visibility.” Consider the De Blasio administration’s use of police and sanitation workers to harass those on the streets and his public statement that panhandling should be illegal. As the saying goes: out of sight, out of mind.

We need to call for the defense of people living on the street and their encampments, respect the safety strategies of homeless people, and not permit the continued demonization, stigmatization and criminalization of people who survive together in makeshift arrangements. Outreach workers must be given sufficient housing resources to offer to those on the street, and we must embrace a response to homelessness that grants access to housing without unnecessary and harmful bureaucratic barriers.

Mental illness, housing, and city subsidies

In discussing Saturday’s murders, some pieces have focused on mental illness among street homeless people. For example the New York Post noted “many, perhaps most [street homeless people], are mentally ill, who object because they can’t decide what’s best for themselves.” Vague references to “mental illness” in relation to homeless folks reinforces false ideas about why people become homeless, and in doing so, disguises issues of gentrification, affordable housing, and racism as matters of individualized illness. It is true that many single individuals living on the street struggle with serious mental illness – and it is also true that many don’t. But either way, suffering from mental illness is not the reason people become homeless – correlation is not causality; many individuals with serious and persistent mental illness do not become homeless. The central reason for homelessness is exorbitantly high rents that can’t be paid with low incomes.

For homeless people with serious mental illnesses like schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, supportive housing (subsidized units accompanied by social services) is typically the answer put forth by politicians, researchers and advocates. However, homeless people in New York City face a dizzying maze of requirements in order to access the limited units that may be available. Although supported by deep evidence of success, the State, New York City and many supportive housing providers have refused to truly embrace a low-barrier ‘housing first’ approach, which in essence means giving homeless people access to housing as a beginning point of engagement rather than putting them through seemingly endless bureaucratic barriers to reach it.

Supportive housing, as is often pointed out, is in extremely scarce supply, and the Governor has repeatedly delayed the release of allocated funds for more of these units. But problems with accessing supportive housing go beyond that. Decisions of who deserves housing are left to service providers with limited accountability or oversight. For example, multiple years of data released through Freedom of Information Law (FOIL) requests show that individuals are routinely denied access to housing based on cursory and surface-level assessments, and the ability for providers to deny with little to no accountability has meant that providers pointedly reject many homeless people with the most needs. For example, the Times piece mentioned earlier noted that one of this weekend’s victims “spoke both Mandarin and Cantonese.” In FOIL data returned to us, there was a September 2018 case of a woman who had already been approved by the city’s Human Resources Administration for supportive housing, but was subsequently rejected for a placement by a supportive housing provider because, “client speaks Mandarin due to language barriers and severity of mental illness client will need appropriate accommodations to support her daily living” (sic). The Department of Homeless Services (DHS) was fully aware of this, as they have been of thousands of other unreasonable rejections that saw no intervention by city officials.

The supportive housing industry has challenged and stopped City Council bills that would require even the most basic transparency and public reporting on denials, but it’s an open-secret amongst providers that applications are routinely cherry-picked and rejections are routinely given without transparency or accountability. Politicians have ceded vast say to industry lobbyists rather than sticking to what the city’s own data actually show about supportive housing rejections: thousands of unreasonable and unacceptable denials for housing. It’s also of note that the city does not track what happens to someone when their supportive housing application expires, meaning there is no mechanism in place to help ensure they eventually end up housed. The state and city could mandate oversight of supportive housing rejections, they’ve just chosen not to.

Beyond supportive housing, the city could also be doing much more to move homeless New Yorkers into affordable housing. Under this administration, the city instituted new rental vouchers called CityFHEPS, but the amounts are woefully inadequate and street homeless New Yorkers can’t even access the vouchers until they have documentation of 90 days of DHS-contracted case management, a requirement that keeps New Yorkers on the street longer and shuts out access for those who are not connected to those services. Furthermore, the mayor continues to oppose the House Our Future NY effort, which is a proposal that would increase the number of affordable units available to the homeless under his citywide housing plan.

Homeless youth and housing

A more in-depth New York Times story, published online late Sunday, explored the murders in Chinatown and quoted a report that residents and outreach workers have struggled with the presence of homeless youth: “Over the past three years, complaints have increased about these younger arrivals, and the police and homeless outreach workers have said that “traditional outreach is not successful with this population.” However, the story does not acknowledge the De Blasio administration’s refusal to provide adequate services or housing options for homeless youth and young adults.

In the administration’s homeless plan, published in 2017, officials stated the goal of giving homeless youth access to rental subsidies. This has still not happened. When it does, advocates believe that subsidies for homeless youth will be in very short supply and only go to a very small set of young adults. What this means is that most homeless youth will have no housing after they age-out of youth shelters at 21, or most homeless youth engagement programs at 24 or 25. According to city data FOIL’d by the Coalition for Homeless Youth, in fiscal year 2018, of thousands of youth served only 35 young people exiting crisis or transitional beds in the youth homeless system were placed into supportive housing, and only 86 moved into their own apartment.

Homeless youth providers have, for years, pointed out that traditional adult-focused outreach methods are ineffective for engaging youth. An easy way to understand this is that many adult-focused outreach teams come in vans emblazoned with organizational logos and various types of uniform emphasizing that they serve homeless people. But many homeless youth and young adults are terrified of being seen by peers or others as homeless, and they dodge these teams. In fact, being seen as homeless can put many of them at risk for attack by others due to their vulnerability on the street. Youth-focused outreach teams are much more successful with this population, but the city only provides the barest funding for youth-focused outreach.

Youth who are homeless, whether they be “travelers” or not, have for decades congregated in Chinatown. This is not new – homeless youth outreach teams have targeted the area for outreach for many years. But as police have pushed more young people out of the Tompkins Square Park and Union Square areas, more youth may be showing up in Chinatown. A common underlying factor is the gentrification of working class areas and culture of New York City. As Chinatown deals with the pains of gentrification, and as development targeted toward the wealthy has expanded, those frustrated with the presence of street homeless people have become louder.

The vicious attacks on Saturday morning have led to a sort of public grieving for many in Chinatown, who have been inundated with reporters looking for interviews during an exceptionally painful time. Many community members are calling for compassionate responses and increased services and resources to help homeless people exit homelessness. Some are calling for more policing. We implore the city and communities to engage homeless youth providers and homeless youth themselves – listen to their expertise about what is helpful and what is not. The reality is that the overwhelming majority of homeless youth are people who have experienced severe adversity and often suffered trauma in their lives, and are much more vulnerable to being victims of violence than they are to initiating violence.

Where to from here?

On Saturday morning, one of the authors of this piece went to Chatham Square in Chinatown. Individuals walked across parts of the square and stood speechless, staring at the NYPD vans and seemingly lost in tragedy. Community members have lost friends and regular faces in the most brutal of ways. On a bench in an area taped off by police, where one of the murdered men reportedly used to sit, was a letter and a rose. Scribbled in marker on the bottom of the letter were the words “God loves us all. May he keep you and restore you we pray.”

The community of those who were lost, advocates, service providers, city officials and others across the city and country are grieving and processing. But we need to be careful. One brutal incident should not be made into generalizations about homeless people, and panic caused by trauma and fear after a tragedy can lead to quick and punitive political and policy solutions that, in the context of a growing anti-homeless sentiment across the city, may only make life harder for those living on the streets.

Rather, these brutal murders should serve as a wake-up call to our politicians, our institutions, and our communities. Instead of dehumanizing, otherizing, scapegoating, and blaming our fellow New Yorkers for our city’s housing crisis, we can make other choices. We need much more housing that is affordable for and accessible to homeless people, we should embrace housing first approaches, and should challenge NIMBYism at every turn. We also need to genuinely meet homeless folks where they are at—which is often on the streets—and not banish them or criminalize their existence. Policing and stigmatizing will not solve the crisis of homelessness, only housing and basic dignity will do that.

Davis, Hughes and Strom all work with the Benefits Team of the Urban Justice Center’s Safety Net Project.

0 thoughts on “Opinion: Murders Demand a Deeper Look at How We Treat the Homeless”

My son was homeless in Ny . They don’t help them at all .

All the police due is ticket them. Push them around. Treat them like animals. Worst I rescue animals…