City Limits / Jeanmarie Evelly

An empty storefront on 125th Street in Harlem.

A Department of City Planning report that examined 24 commercial neighborhoods across the five boroughs found a small increase in storefront vacancies over the last decade — but says the uptick cannot be blamed on rising rents alone, citing multiple factors, including a rapid market shift in the economy due to technology and changing consumer preferences.

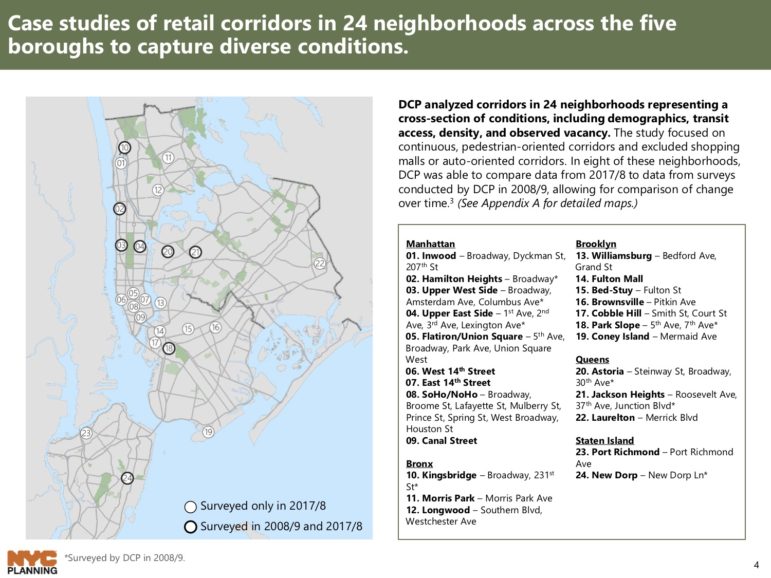

DCP analyzed 10,000 storefronts using third-party data from LiveXYZ, a web application that describes itself as a real-time events mapping site, based on on-the-ground surveys in two dozen commercial corridors. It found the average vacancy rate in these neighborhoods — chosen for their role as “pedestrian-oriented retail corridors” that represent a broad cross-section of different street conditions — increased from 7.6 to 9 percent between 2008-09 to 2017-18. The report did not look at auto-oriented areas or malls, according to DCP.

The analysis follows a push by advocates and lawmakers for more definitive data on city businesses. At the end of July, the City Council passed legislation to track vacant storefronts by requiring property owners to register their empty properties with the city’s Department of Finance. The Department of Small Business Services (SBS) will be tasked with running the database, which will include a summary of storefronts, lease information and monthly rent. The bill is awaiting Mayor Bill de Blasio’s signature.

“In an ever-changing city where neighborhood shopping is an important facet of urban life, it’s crucial that we put as much reliable data as possible into the hands of business owners, residents, policy makers and elected officials,” said DCP Director Marisa Lago in a press release announcing the storefronts report. “DCP’s research shows that the reasons for storefront vacancies are complex and varied and that solutions must be nuanced and targeted — or we may do more harm than good.”

The DCP report describes a rapid shift in the local retail industry due to a rise in e-commerce technology and changing consumer preferences. These changes include a decline in dry goods stores and jobs in the city — those that sell textiles or ready-to-wear clothing — but an increase in the food, beverage and services industries. The report also points to a rise in the supply of storefront space due to new construction in competitive neighborhoods such as Williamsburg.

And while some neighborhoods experienced a rise in commercial rents, others saw their rents decline, according to the findings. The report found that vacancy rates differed from community to community, and could not cull a single factor as the cause behind them.

While DCP says storefront vacancies are not “pervasive” citywide, it did find that they’re high in certain neighborhoods, such as SoHo/NoHo or Williamsburg, which had vacancy rates of 13.8 and to 16.6 percent, respectively. High vacancy rates were attributed to several factors, such as market shifts within the industry, an area’s ability to attract consumers and compete, conditions of the building stock and community perception, zoning and/or landmark regulations and redevelopment of properties.

This concentration of storefront vacancies were often found in certain neighborhoods identified by the city as “hot corridors” — more established commercial hubs that are rapidly changing, and where property owners “kept spaces vacant while seeking high rents.” The “hot corridors” had medium to high vacancy rates and include the Brooklyn neighborhoods of Bedford-Stuyvesant, Park Slope, Cobble Hill, Williamsburg and Fulton Mall. In Manhattan, Canal Street,14th Street (East and West), SoHo/NoHo, Upper East Side, Upper West Side and in Hamilton Heights also had medium to high vacancy rates.

Other areas are defined in the report as “underperforming corridors” — neighborhoods with medium to high vacancy rates that have experienced “long-term historic disinvestment” and a difficulty attracting consumers due to perception, or lack of anchor stores that bring in a loyal consumer base. These include Brownsville, Coney Island, Longwood and Port Richmond, according to the report.

Neighborhoods with low vacancy rates and a steady customer base included Union Square and Flatiron in Manhattan, as well as outer-borough corridors like Astoria, Inwood, Jackson Heights, Laurelton, Morris Park and Kingsbridge in the Bronx and New Dorp in Staten Island, the report found.

Advocates and experts who have been studying storefront vacancies across the city said the city taking initiative and putting out the report is good news, but they wish it would have made such data publicly available sooner.

“The commercial landscape needs better information,” said Lena Afridi, director of Economic Development Policy for the Association for Neighborhood and Housing Development. She added that there are “a few red flags,” with the study, including that it relies on data from a proprietary source.

“It may not be the most reliable,” said Afridi, who would have liked to see input from community-based organizations or merchant associations. In the report, DCP said it reached out to local partnerships and business improvement districts (BID) for information. “Nevertheless, we are still happy about the report being released.”

Other experts said the report’s findings were not surprising, but did raise more questions about the causes behind storefront vacancies, and that additional context might be needed to understand the full picture.

“What’s happening in one neighborhood cannot always be explained by what’s happening in another, and the report’s big takeaway is that there are [many] factors that contribute to these vacancies. And it’s going to depend on the context of those vacancies,” said Rachel Meltzer, an associate professor of urban policy and chair of the MS Public and Urban Policy program at the Milano School of Policy, Management, and Environment.

That context includes what type of commercial space is vacant and for how long, she adds.

“It’s what I call the spatial spillover effect. So if you have one vacancy, does it lead to more vacancies in that area? So [the report] the didn’t look at that,” Meltzer said “On average, you could be seeing not such dramatic differences, but it’s also interesting because the retail sector relies a lot on this clustering of activity rate. It’s rare that you see one standalone retail [space].”

This type of “clustering” includes corridors that are home to several of the same types of businesses that offer competitive services, and the idea is for the consumer to comparison shop. Another function for clustering is offering complimentary services in one corridor, such as having a butcher shop next to the cheese shop, next to the wine shop, and so on.

The cost of rent is an issue too, but for more competitive, active corridors such as SoHo, Meltzer says. A property might be vacant because its owner is tied up financially, or the landlord could be waiting for a better leasing opportunity. When small businesses shut down due to rent, it’s often because rent is the last straw for a struggling store, and that is where city services could come in to support small businesses by providing tools so they can adapt to a shifting consumer base or survive the economic bumps they might experience as the market shifts.

Meltzer says the report helped identify the myriad forces at play when it comes to store vacancies, from the rise of e-commerce to gentrification to the direct role the city can take in creating supportive policies for local businesses.

“That’s what’s happening I think in cities all over the country,” she says. “There’s no question that the retail market is changing for a lot of different reasons, but the local context needs to respond to those changes.”

You can read the report in detail here.

3 thoughts on “Many Reasons Drive City’s Storefront Vacancies, Report Says”

There are numerous vacancies in Trbeca, along Greenwich and Hudson Streets, that have continued over 1 year or more. This is a high income residential area and the are many office buildings, like Citibank— both factors that should make these streets lucrative commercial corridors. The report does not explain the high vacancy rate for TriBeCa. I understand this neighborhood was not in the study, however my point is the situation defies logic and the report’s generalizations.

It’s amazing…all this reporting and data and I haven’t seen any mention of the extremely high commercial property taxes in any of these areas. It is one of the main reasons rental costs have sky rocketed. Take a mixed use building of 4 stories…less than 12 tenants in a low to moderate shopping district…How does a property owner afford $40,000 plus a year for property taxes and still maintain the building…especially when the law favors tenants who decide to withhold rent? We must stop the landlord witch hunts and see the problem from both sides. The city may think it can fix the problems and fill the spaces, but it will never happen until there is a moratorium on property taxes starting in specific retail districts.

Pingback: August 30, 2019 - Weekly News Roundup - New York, Manhattan, and Roosevelt Island | Manhattan Community Board 8