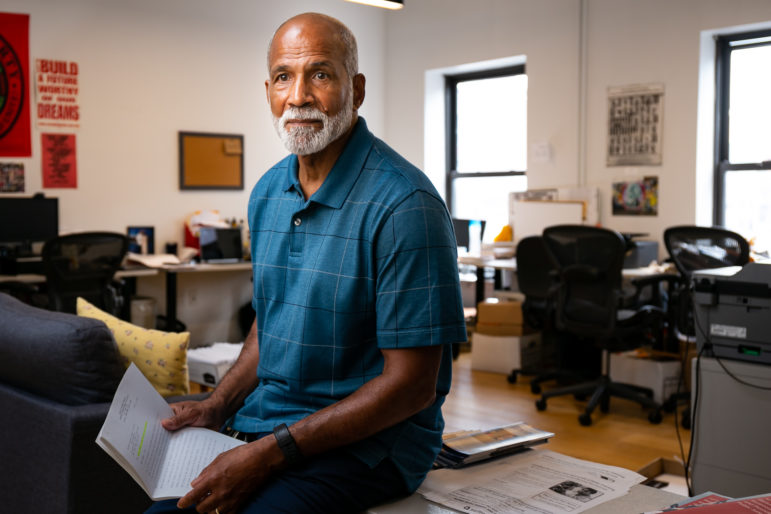

City Limits / Adi Talwar

Jose Saldana, 66, a community organizer with the Release Aging People in Prison (RAPP) at his office on Canal Street in downtown Manhattan. After being denied parole four times, Saldana was released from the New York State prison system in January 2018 after serving 38 years.

When Sammy Cabassa stepped onto the sidewalk again after 34 years in prison, he found it dizzying. The then 60-year-old was granted parole – after his 4th parole hearing in 5 years – in 2017. When he walked back into the city he left as a young man, the bright lights were hard to adjust to, after years of spending almost all of his time in dimly lit facilities.

His disabilities made things worse; he lost vision in his left eye to macular degeneration, one of many conditions undertreated in prison. He walked with a cane.

He spent his first night back in the Bellevue men’s shelter on 30th Street. He had no other option, given just $26 in emergency assistance upon discharge. There were no working elevators. He didn’t sleep at all that first night. He was going from a closed cell to open, dorm-style housing with 80 others, where robbery and violence are common.

When he eventually moved to a single-room occupancy apartment (SRO), HRA provided $250 in rental assistance, but he had to come up with the other $435 on his own, relying at first on friends and his daughter.

The room is 11 by 10 feet in length and width, and is where he fits all his clothing, food, a TV, a laptop, a CD player. At times, he says, returning home to the tiny space reminded him of the cell he left.

Decades outside of society can have stark consequences for those who eventually gain freedom: Incarcerated elders lag behind in terms of health, finances and support networks. Despite this, reforms that could get parole-eligible elders a hearing before New York state’s parole board – a step toward having more people leave prison before they’re physically frail and giving them more time to acclimate to society – have been shelved repeatedly, even this year during a legislative session packed with criminal justice reforms.

Reforms enshrined in this year’s state budget ended cash bail and pretrial detention in most cases, allowed more evidence to be shared earlier with defense teams and required speedier trials. But other key changes didn’t come to fruition; among them a bill to limit solitary confinement, and another to mandate parole hearings for people over 55 who have served at least 15 years in prison.

The parole proposal sparked controversy, drawing heat from police unions and Republican senators. While much criminal justice reform debate centers on forgiving low-level crimes, the convictions handed down to elderly people in prison are often for violent offenses. A study found that across the country, sentences for violent crimes have only gotten longer, even as other reforms have set in.

And parole hearings for people with such convictions can be politically toxic. The 2018 parole of Herman Bell, who was convicted of killing two police officers in 1971, drew outrage from the NYPD and police unions. Governor Cuomo opposed his release, and Mayor de Blasio wrote a letter to the parole board calling the decision “incomprehensible.” The parole this May of Judith Clark, who was convicted of felony murder of police officers for her role in a 1981 robbery, drew similar scorn.

Meanwhile, the aging of prisoners in the U.S. is growing epidemic. Between 2007 to 2016, New York State’s overall prison population decreased 17 percent, while the number of inmates aged 50 or older increased 46 percent, and now comprise about a fifth of the population. The growth is a result of harsh sentencing laws in the 1970s and 1980s.

Experts believe that incarcerated people age faster than people on the outside, and age 50 is generally considered elderly for this population. Research has shown that people that old have largely “aged out” of crime and are at low risk to return to prison. In 2012, only 7 percent of those in New York State aged 50 to 55 returned for a new conviction upon release. And the costs for keeping elders locked up are higher than for the rest of the population: An ACLU study found it cost $68,000 a year to house a prisoner age 50 and older.

Price paid for years of poor healthcare

The parole bill, if passed, could free some people from years of facing the health consequences of incarceration. Upon release, many would likely have to seek medical help for undiagnosed or poorly treated problems.

People in correctional facilities are guaranteed healthcare by a 1976 Supreme Court decision. But that healthcare, according to formerly incarcerated New Yorkers who spoke with City Limits, is threadbare, and that neglect is felt on release.

Laura Whitehorn, 74, is a co-founder of Release Aging People in Prison (RAPP) and served 14 years in a federal women’s prison for her role in a series of bombings in the 1980s. In prison she was injured in a fall, slipping on a floor that was newly waxed and polished for a prison tour. She never received an X-ray for what she later learned was a broken vertebrae and extensive damage to her lower back.

When Cabassa was released in 2017, he was battling all sorts of health issues he’d accumulated in prison; he had degenerative arthritis of the back, knees, shoulders, and there was the issue with his eye.

“There’s a sense of having to catch up with medical care,” Whitehorn says. “When you get out you have no idea all the aches and pains are normal or an indication of something bigger.”

Sekou Shakur is a formerly incarcerated friend of Cabassa’s who works at a re-entry program called Bronx Connect. Shakur spent 34 years in New York prisons for convictions including attempted murder and weapons possession. Since he’s worked in re-entry, he’s seen many people come home with serious illness and disabilities and immediately require serious medical care: knee surgeries, hip replacements and eye exams that went undone.

“We had a client who had severe glaucoma and didn’t even know it,” he says.

The result is that often elders released from prison die within a few years. RAPP and other formerly incarcerated advocates were chilled by the death of Charles “Chas” Ransom. Ransom was an organizer and mentor to others, and a facilitator for a Tribeca Film Institute film series within Otisville Correctional Facility. He was interviewed by Oprah Winfrey at the Tribeca TV Festival. Ransom was released from prison in June 2017 after serving 33 years, and was set to take a job as a re-entry specialist. But he died that October of a heart attack, less than 90 days later.

And one of RAPP’s co-founders, Mujahid Farid, died just last November, at the age of 69, after just seven years the outside. He was eligible for parole after 15 years for a conviction of manslaughter and attempted murder of a police officer. But he served 33, after being denied nine times, despite being a model prisoner who mentored others on the inside. In his parole denials, the nature of his convictions was cited.

The health impact of fractured family ties

Shakur has also seen many people struggle with finances when re-entering society. “The older they get, the more difficult it is,” Shakur says.

Formerly incarcerated people are 10 times more likely to be homeless than the general population, and rates of homelessness are higher the older that person is, according to Prison Policy Institute. The Institute’s study found that credit checks, large security deposits and time outside the labor market were among the factors.

Adding to the challenges elders face when re-entering society are fraught social networks, something with material consequences for housing, finances as well as mental health. When Cabassa was released, he sought to repair relationships with his children, one of his biggest challenges. His daughter is now grown, over 40 years of age, and married. The tension proved hard to overcome.

“When I came home, all the memories were washed away,” Cabassa says of attempting to connect with his daughter. He understands the bitterness she may feel – he was incarcerated for almost all of her life, missing every key moment of her growth into an adult. “I know she holds it against me,” says Cabassa, whose wife died of AIDS in 1995.

The loss of time and dissolution of bonds with loved ones can have an impact on one’s heart, figuratively and literally. Countless studies point to the health risks of loneliness among elders.

“Over the years, as you get older you lose connection,” says Jose Saldana, 67, a RAPP staffer who served 38 years in prison. “I mean, I’ve lost my dad, my mom, my uncles, my aunts. All of them passed away while I was in prison.” He was fortunate, he says, to have strong relationships with his children, his siblings and extended family, but says this is a rarity. Many people leave prison without such bonds, and Saldana believes the lack of strong connection leads to worsening health and premature death.

“Having that positive, loving contact with people,” Saldana says, “if you don’t have that, you know, we’re kind of counting our days.”

New scrutiny for the parole board

Twelve members currently serve on NY State’s board of parole, and seven more seats remain unfilled. Hearings can be incredibly brief, sometimes lasting only a few minutes. The board is understaffed, and sometimes hears up to 70 cases a week. The governor’s office has cited cost as a reason not to fully staff up the parole board – each member of the board is paid over $100,000 a year. But DOC’s budget is $3.2 billion.

And who is on those parole boards matters. This year, Cuomo nominated six new parole board commissioners – one, Richard Kratzenberg, a former corrections officer, drew criticism from advocates for testimony in which he emphasized the nature of the crime in his decision-making. He was not confirmed.

Of the five others, RAPP takes issue with an emphasis on law enforcement background and not social work or trauma experience. “Where were the nurses, substance-abuse counselors and mental health professionals?” the group said in a press release.

Often, people who are eligible for parole don’t even receive a parole hearing. For the most violent crimes, especially ones involving police officers, it is an attempt to avoid bad publicity, according to Todd Clear, a professor at Rutgers School of Criminal Justice.

“The parole board is really trying to avoid all the negative publicity that comes when the hearings even come up,” Clear says.

When the crime is something that has shocked the public, particularly when the victim was a law enforcement officer, he says “it’s very difficult for the parole board to release those people, politically.” Former parole board chairman Robert Dennison expressed this to City Limits in 2014, saying parole commissioners had a perverse incentive to not hear the cases of violent offenders, as controversy could hinder their reappointments.

When many who are convicted of violent crimes do get a hearing, the nature of their crime is cited as a reason for denying parole—a signal that the commissioner did not believe the person should have been granted a hearing in the first place.

Cabassa remembers a parole hearing in August of 2012. He walked into the room, faced with three commissioners sizing him up. “The minute I came in, you could cut the tension through that audio-visual scene with a knife,” he says. The commissioners shunned his responses, he said, and seemed unsympathetic to any change he had made. He was denied parole until 2014, essentially sentenced to two more years in prison. The nature of the crime—attempted homicide of a police officer, which Cabassa denies happened, and brought a conviction he could not change—was cited. He was denied again in 2014 after going before the same three commissioners.

On his third parole hearing, only two of those commissioners were on hand to hear his case; the third person on the panel was a new Cuomo appointee. Cabassa had with a letter of support from his attorney. One commissioner teared up, he said, seeing the letter of support, saying it was unlike anything he’d ever read from an attorney.

The commissioner asked him, “Sammy, is it over?” asking if he would return to prison if released. Cabassa broke down, he says. “All I want is to give back. I understand my criminal behavior,” he told the commissioner.

Pam Neely, now 59, was incarcerated at Nassau County Jail on and off from her mid-twenties to early 40s during a period of heavy drug use. She says her experience with parole boards is similar, and she saw many people who had dramatically changed their lives for the better either not granted a hearing or denied parole. It matters little how much the person has changed their life.

“You’re doing it for your own life,” she says of the changes people make. “They don’t look at none of that.” Most, she says, end up dying behind bars regardless of how much they may have changed.

The question of violence

RAPP has been at the forefront of advocacy for parole reform, pushing two bills intended to grant more hearings and make it harder to deny parole based on the nature of the crime.

The Fair and Timely Parole Act was introduced by Sen. Gustavo Rivera in the State Senate, and was endorsed by progressive newcomers Zellnor Myrie, Jessica Ramos and Julia Salazar, among others. The bill would have required the parole board to find a public safety concern if they deny parole, emphasizing current risk over prior conviction.

The elder parole bill, which would ensure hearings for people 55 and up after serving 15 years, was introduced by Sen. Brad Hoylman and was voted out of the Crime Victims, Crime and Corrections Committee with five “yes” and two “no” votes.

Neither bill made it to a full Senate vote. Other legislation to reform the process for handling parole violations also failed to move forward in 2019.

RAPP staffer Jose Saldana, who was released in 2017 after 38 years in prison, said many opposed the elder parole bill because it would have effectively eliminated sentences of life without parole. But those sentences are precisely what Saldana and allies say are not compatible with a system that aims for rehabilitation, and not just retribution.

“Any sentence that eliminates the possibility of transformation we believe is inhumane,” says Saldana. Saldana and RAPP believe that fighting for an undiluted bill is important to advance the conversation and talk about violence. The governor’s budget proposal in January floated an expansion of medical parole, but RAPP said the parameters were too narrow and rejected carve-outs for certain violent convictions.

Ultimately, the group believes pushing the elder reform bill will prompt conversations on violence, redemption and punishment that many avoid. While a broad consensus has come to see low-level drug offenders as undeserving of disproportionately long sentences, the same sympathy is seldom extended to those who’ve been convicted of the most violent crimes, regardless of what kind of transformation that may have had.

“We’re talking about people that committed violent crimes. I committed a violent crime,” he says of his own conviction for a 1979 shootout in which a police officer lost an eye. He was denied parole four times over 38 years. He says most of the elderly prisoners he shared time with are no longer the same people who acted violently in their youth. “I’ve been in prison for 38 years. It didn’t take me 38 years to transform,” he says. “It doesn’t take anybody that long.”

The city’s Police Benevolent Association is the most outspoken lobby against parole reforms, particularly for people convicted of violent offenses against police officers A tab on the PBA website titled “Cop Killers” allows visitors to send e-mails to the parole board, asking that people who killed police officers not be set free.

In an e-mail to City Limits, PBA President Patrick J. Lynch said, “Aside from the fact that today, 55 years old does not qualify as ‘geriatric’ in anyone’s book, the concept of parole based upon age is devastatingly flawed on several levels.”

Lynch cited a Bureau of Justice statistics study on rearrest rates for state prisoners, a U.S. Department of Justice study on recidivism for violent crimes, and a U.S. Sentencing Committee study on people over 60 with firearms offenses.

However, of the studies cited, two did not pertain to the over 55 population who would get hearings under the elder parole bill, whose recidivism rates are the lowest in the carceral system. The third study by the US Sentencing Committee showed a 30 percent recidivism rate for firearms offenses in people over 60, although it pertained to federal, not state charges.

Elders who have committed more violent crimes, including murder, are among the least likely to recidivate. From 1985 to 2012, less than 2 percent of those who served time for a murder conviction in New York returned to custody after release, compared to 14 percent of people with any type of conviction released statewide.

Difficult politics around parole

There are trickles of policy reforms across the country meant to ease sentencing for violent crimes. A 2014 Mississippi law walked back its embrace of truth-in-sentencing laws stemming from the 1994 crime act. The 1994 truth in sentencing law incentivized states to delay parole indefinitely by dangling federal funding. In Pennsylvania, the state with the most parole-ineligible life sentences, the Philadelphia DA has endorsed a parole bill that would mandate parole eligibility after 15 years served.

“That is the crux of our politics,” Whitehorn says about the emphasis on violent crimes.

“[It’s about] changing the narrative to see that we can’t un-do the crisis if we don’t deal with the question of violence and see that people who commit violent crimes can live purposely productive lives.”

The tendency to tie incarcerated people to their original convictions and ignore personal growth and accomplishments is one of the reasons the elder parole bill was coupled with a Fair and Timely parole bill, which would make parole presumptive, de-emphasizing the original crime as a blanket rationale for rejection.

But Republican Sen. Pamela Helming said in a press release that the bill would lead to the release of “hundreds of hardened criminals, including child molesters, murderers, rapists, and drug traffickers.”

Helming, like many opponents, depicts parole as being insensitive to victims of crimes, and in her press release quotes a woman whose mother was murdered, as well as a woman whose grandchild, a toddler, was murdered. Helming opposes the potential commutation of life without parole sentences, saying, “Those who have stood trial and been convicted and sentenced for committing horrific acts of violence and abuse should serve their full sentence.”

Whitehorn often hears opposition to parole framed as being for victims, but points out that most victims oppose harsh sentencing. And most perpetrators of violence were victims of violence themselves.

Saldana says a version of the elder parole bill might have passed this session, but the governor wanted a version with carveouts for people who had been convicted of serious crimes, including killing a police officer. Saldana and RAPP said no. A compromise of this type would have deflated the purpose of this bill, he says. And he would feel as though he were letting down people he left in prison.

“I left people inside. They deserve just as much as I do if not more,” Saldana says. “I can’t offer some of the guys I left behind hope, and then the other ones death by incarceration, I just can’t do that.”

Todd Clear points out that the bill itself could normalize a conversation that is pushed to the periphery and treated as spectacle when it happens. If people over 55 are mandated parole hearings, then they will be common place, less likely to spur tabloid editorials or political opposition when a potential parolee has committed serious violence.

“It will be routine stuff. The fact that a person who committed a serious crime is having a parole hearing will not be crazy,” he says.

A public safety argument?

Saldana and others argue that there is a public safety benefit to releasing elders from prison. Many of them have become mentors to younger people in prisons and can provide guidance to people on the outside who are caught up in violence. Such anti-violence programming is underfunded: After gun violence erupted at a Brownsville block party last month, community leaders decried the city’s underfunded Cure Violence initiatives.

“Why would you not want more of them out there? If it’s about revenge, then let’s just say we’re about revenge,” Saldana says. “I’m not unique. There’s literally thousands of people just like me,” he says about his rehabilitation. “And most of them will die in prison. “

Sammy Cabassa, despite troubles returning to society, is among the success stories Saldana says are possible. Sober for 31 years, he was able to take courses at Hostos Community College in the Bronx, and is now a certified recovery peer advocate and trainer, helping others, often younger people, overcome substance abuse. The courses were funded through a vocational program for people with disabilities called ACCES-VR.

But Cabassa is one of the exceptions. Whitehorn sees many others who falter, and wonders what could have been if they were released to the community earlier. “You see people struggling for money, housing,” she says, “the whole time there’s a sense that this is so unnecessary.”

6 thoughts on “Advocates for Aging Prisoners Look to Force a Debate on Parole”

Crazy how people think someone guilty of killing people should be granted release. How should they be afforded remaining years of comfort while their victims didn’t? 15 years isnt even enough for murder, a whole life gone and family effected. Yet hey if they are old, let them out.

Elder parole is about the dumbest thing I have heard yet! When that person is sentenced to “life in prison without the possibility of parole” it is just that…spend the rest of your life in prison. Period. Death Penalty is no longer in force or effect so, you as you have taken a life, you forfeit yours in a free society and are rightfully incarcerated. Now, because the incarcerated person is getting old and infirm we now have to have compassion for them due to their age victims be damned. To them I say, you were sent to prison for life due to your heinous crimes, the heinousness of that crime has not diminished in the years that have passed

We understand that people change and restorative justice teaches us that more harm doesn’t undo past harm. Many of those who have spent decades in prison have truly changed and deserve a second look, something that is absolutely the parole board’s job.

I am looking for assistance for a federal inmate who has a life sentence. He’s been in prison since he was 19 years old and is now in his 60’s. He has a parole hearing on October 2021, and we are desperately looking for someone to assist him with this hearing. Do you know of anyone that I can contact for assistance for this gentleman I’m trying to assist? He doesn’t have any money, and not much family. I’m doing some leg work for him, pro bono cause — sometimes you just have to help those who can’t help themselves. Your time is appreciated greatly!

Lisa

They are more productive living in society working for and contributing to society than behind bars with us paying there way …

If prisons are supposed to reform, it seems that taxpayers are being ripped off by a system that has failed miserably.