NYBC

Floating homes in the Big Apple? A new report says NYC should look into it.

New York City should permit property owners in uniquely vulnerable coastal areas to sell building rights to inland developers as a way of discouraging new construction in communities most at risk of climate change.

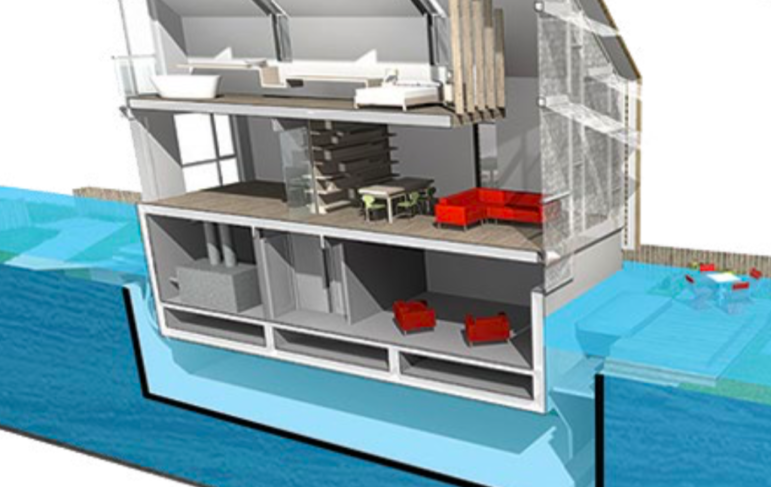

So says the New York Building Congress in a report issued Thursday that also calls for more comprehensive planning for climate change and for steps to allow New York to “build with water” by experimenting with floating and amphibious structures.

Along New York’s 500 miles of coastline, rising sea levels and the increasing risk of severe weather create not one problem but several different ones. For instance, JFK Airport, source of billions of dollars of economic activity and impossible to relocate, sits on the waters edge. But so do residential parcels with the potential for further development that might increase the number of people at risk.

Hardening coastal defenses might be the sensible way to protect some of the city’s waterfront assets (including the majority of its in-town electrical generating capacity, which lies in the flood plain). But tidal gates, sea walls and berms might not offer practical protection for other property—and, more important, people—in coastal “prevention” zones.

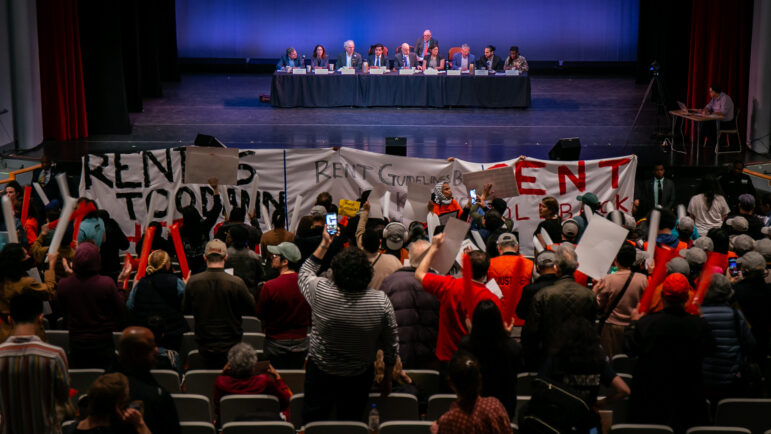

Hence NYBC’s idea to allow property owners on the coast to use transferable development rights to benefit from their property without developing on it. “The city … should restrict development in prevention zones and allow affected property owners in those zones to sell their development rights to sites in protection and promotion zones,” the report reads; “promotion zones” are defined as “upland or inland where development is safe and should be encouraged.”

“This proposal provides an equitable solution with financial compensation for restricted property owners and encourages smart growth by shifting development and density away from vulnerable and towards safe parts of the city,” the report argues. NYBC names the Rockaways as one of the “vulnerable areas where development should be discouraged.” (Asked if the report indicated that the de Blasio administration’s rezoning of downtown Far Rockaway was unwise, NYBC says it was referring to other areas of the Rockaways that are more vulnerable.)

Not that there couldn’t be some new development at the water’s edge, or even in the water: The report points to cities like Amsterdam, London and New Orleans where “there are now floating homes that can move with tidal fluctuations and storm surge while remaining anchored in place” as an example to New York.

Figuring out how shoreline “armoring,” prevention and promotion zones, and floating neighborhoods might work in concert will require comprehensive planning “by a regional authority that centralizes and mandates resiliency efforts across various government agencies and municipalities,” NYBC says.

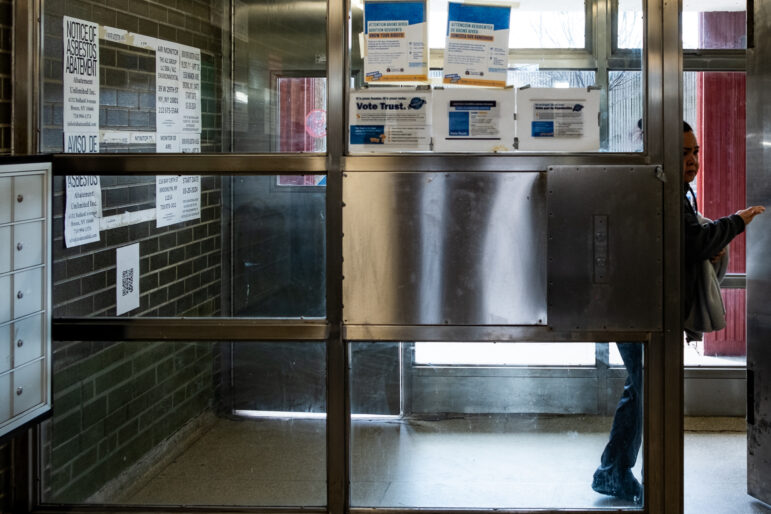

Implicit in the report is one of the puzzles that authority would wrestle with: the status quo. It’s one thing to direct future development away from the coast or onto floating platforms. But that doesn’t address what current property small property owners on the coast—in places like Edgewater Park of the Bronx, which might not be adequately protected by shoreline defenses for decades—are supposed to do.

“Property owners and developers should design and retrofit buildings to mitigate flooding,” NYBC says. “They can install floodproofing, such as deployable barriers, as well as elevate buildings, mechanical equipment, streets and land,” the report reads. Which is true. The trick is paying for it.