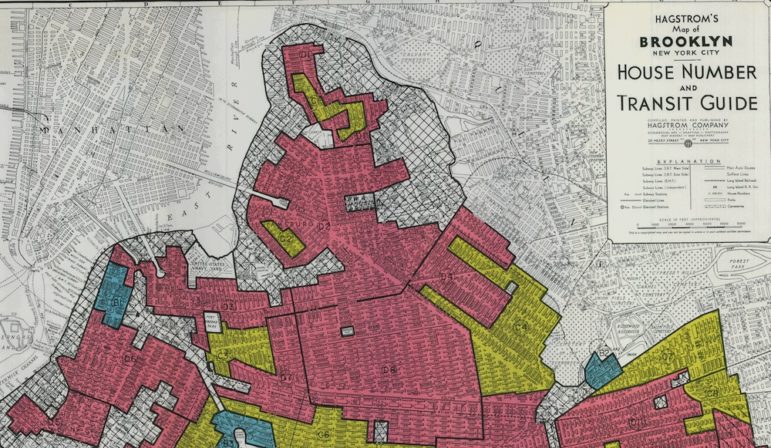

HOLC

A redlining map of Brooklyn.

New York City is in the thick of a process to revise portions of its charter. As the 2019 Charter Revision Commission wrapped up a round of hearings earlier this month, one of the hotly debated issues was the need for a comprehensive planning process for New York City. The commission’s thus far tepid approach to comprehensive planning may well reflect the view that a large, global city like New York needs to retain “flexibility.” (This was the topic of a City Limits event last week; see the video here.)

But such flexibility has all too frequently assumed the form of scattershot land-use decisions taking the path of least resistance in low-income communities of color while leaving wealthier areas of the city untouched—exacerbating rather than mitigating a documented history of racist planning. In the aggregate, this ad hoc approach to land-use planning has not only perpetuated segregation of residents from each other by race and income, but also segregation of many residents from resources and opportunity. It should be no surprise that New York City ranks among the very most segregated cities in the United States.

Maddeningly, city officials will often justify cataclysmic and unwanted interventions in vulnerable communities as opportunities for economic integration. To integration advocates whose actual recommendations for policy reform go repeatedly unheeded by the city, such obfuscation can appear cynical in the extreme.

That is where comprehensive planning comes in: to have a truly integrated and inclusive city, we need to plan for it. That does not mean considering the possible effects of a one-off project or rezoning, but taking the time to think seriously about what it would mean to have the integrated city we want and what it would take to get there.

Comprehensive planning means robust opportunities for localized planning followed by a careful balancing of interests across all neighborhoods according to a framework of citywide needs and goals. It means studying the effects of past decisions to avoid repeating mistakes. It means a lot more affordable housing in higher-income areas, and a lot more sharing of the benefits and burdens of city life. It means acknowledging that plopping new housing for higher-income persons in the middle of a low-income community is not integration if it simply displaces or harms the very people who should experience its benefits.

Get the best of City Limits news in your inbox.

Select any of our free weekly newsletters and stay informed on the latest policy-focused, independent news.

One does not need to be an expert or veteran of land-use fights to recognize that it is impossible for anything like this to happen at the moment of individual land-use and rezoning actions. We need to create a framework to guide each of these proposals.

For example, increased density around transit corridors is one rationale often provided for large-scale upzonings. Yet with our current ad hoc approach, this planning principle is selectively applied, based largely on politics, exempting many higher income, whiter communities. An analysis of the impact of shifting from manufacturing to residential on an individual site is never going to give us a picture of the cumulative impact of numerous such actions across several boroughs on job access for residents. A citywide plan for both job growth and housing development would. The current administration put enormous effort into developing the tool of Mandatory Inclusionary Housing, which is primarily designed to bring affordable housing to wealthier areas – yet in the absence of a plan that incorporates both zoning changes and policy tools, it has been applied primarily in poorer neighborhoods, where subsidized housing is a viable, and often preferable, approach.

Detractors of comprehensive planning have caricatured it as a straightjacket preventing the city from responding to unforeseen circumstances. But comprehensive plans can and do allow for adapting to unforeseen circumstances. With a comprehensive plan in place, however, city officials and communities have the benefit of relatively disinterested analysis about how decisions in one part of the city might affect another. And if circumstances truly do require deviation from previous thinking, the comprehensive plan forces city officials to make this case transparently according to a pre-determined set of values and considerations.

Racial and economic segregation was intentional so its dismantling must also be intentional. Only a comprehensive planning process with stated equity goals can provide the environment, structure, and scope for analyzing the thousands of considerations and tradeoffs that will get us to a rational and integrated city. New York City cannot wait until the next charter revision to adopt the basic planning mechanism that municipalities around the national have used for decades. The time to act is now.

David Tipson is executive director of New York Appleseed, which advocates for integrated schools and communities and is a member of the Thriving Communities Coalition.

6 thoughts on “Opinion: NYC’s Segregation Was Carefully Planned. Its Integration Must Also Be.”

Those redlining maps were outdated by the 1960s and no one was using them so I don’t know why everyone keeps bringing them up. There were racial elements to the maps. But many areas of the city were redlined due to issues like lack of sewers and flooding.

Everyone keeps bringing them up because they had a profound effect on neighborhoods for decades. Saying “there were racial elements to the maps” is like saying the pope goes to church sometimes.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2018/03/28/redlining-was-banned-50-years-ago-its-still-hurting-minorities-today/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.14d45467a8e7

People keep bringing them up because it’s their best rationale for their preferred policies- centrally planned social engineering.

Watch Chernobyl on HBO to see how these ideologues central planning works in practice.

Right, because nuclear accidents never occur in capitalist countries. Three-Mile Island and Fukashima are just the names of cocktails.

and the ad hoc approach that patently produces and reinforces class and racial segregation isn’t social engineering. ok…

Pingback: May readings – Uneven Earth